Plan your visit

Not all Latinos are Mexican: The Story of a 1920s Peruvian Steel Worker from Gary, Indiana

October 6, 2020

During Hispanic Heritage month, it is always important to remind people that Latino and Hispanic cultural heritage is not monolithic. When looking at the size of Latin America we see 30+ combined countries and territories. Within these countries and territories are vast differences in spoken language and cultural norms. Fundamentally speaking, no two Spanish speaking countries speak the same Spanish. Growing up, I observed people from different cultural backgrounds playfully argue which Latin American country spoke the “correct” Spanish. And what about the Latin American countries who do not speak Spanish? On my block we had a neighbor who had two daughters that would visit from Brazil, they did not speak Spanish but Portuguese. As a child this flipped my nuanced Americanized understanding of Latino and Hispanic culture. After all the first colonizers of the indigenous communities of what we presently know as Latin America were explorers from the Iberian Peninsula, Spain and Portugal.

As an adult attending meetings or community conversations regarding the Latino community one of the most common statement that is repeatedly made – “everyone thinks that I or we are Mexican”… “I am not, I am (insert Latino, Hispanic or Indigenous ethnic culture here).” Demographically and historically within the United States there has always been a higher percentage of individuals who identify as Mexican or of Mexican heritage. Before 1848, roughly a third of the present-day U.S. used to be Mexico or a territory of Spain. For further reference, look up the Treaty of Fontainebleau, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Mexican American War.

Indiana’s Latino and Hispanic community is rich in history and diversity. A reminder of this diversity came from a recent reference question forwarded to my e-mail inbox that had to do with Latino genealogy. Marita Huertas from New York City discovered information about her grandfather Miguel A. Agurto, born in 1891 in Paita, Piura, Peru who eventually lived and died in Gary, Lake County, Indiana. Marita’s e-mail inquired about her grandfather’s life in Gary. She was aware that he spent over a decade in Panama. A 1919 employment record shows him as a laborer on the Panama Canal, working for 17 cents an hour (today, $2.55 USD). He spent his twenties working on building this canal which cuts through the Central American country of Panama, revolutionizing trade and logistics by connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. His employment at the Panama Canal spanned from working on the railroad to the docks in the Cristobal Canal Zone (Port of Colon). How, when and why he makes the jump from Panama to Gary, Indiana is a bit of a mystery.

Miguel A. Agurto, 1919; Source: Ancestry.com, U.S. Panama Canal Zone, Employment Records and Sailing Lists, 1884-1937, Container 44.

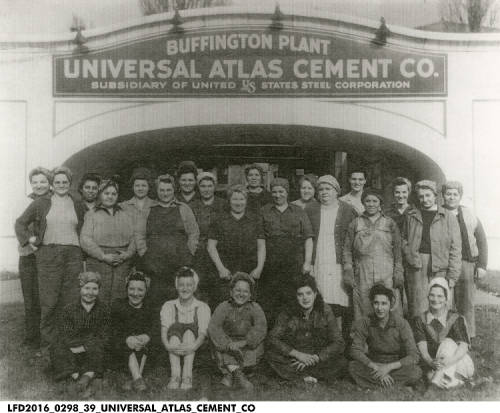

What we do know is that the U.S. Steel Corporation and its subsidiary, Universal Atlas Cement Company, provided both the steel and portland cement needed to build and maintain this waterway. Concurrently Latinos were recruited to work in the steel mills of Chicago and Northwest Indiana in the 1910s.

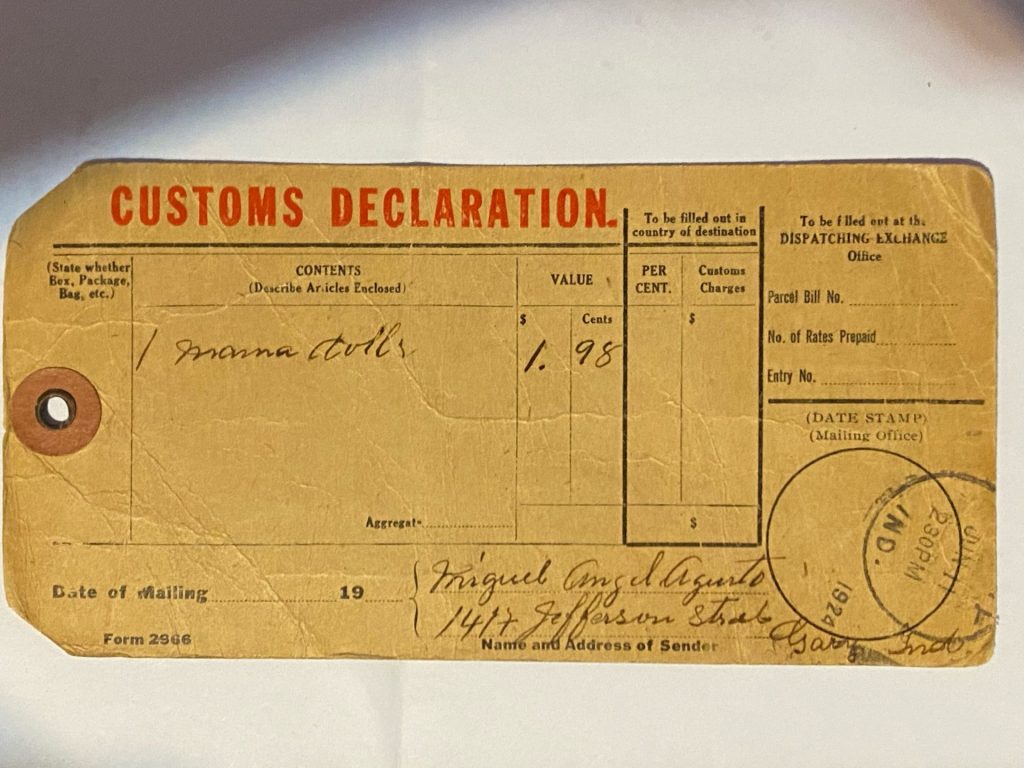

Women at Universal Atlas Cement Company, ca. 1942. Frederick Ruiz Maravilla, IHS

Miguel appears in the Gary City Directory as early as 1929 and is employed as a steel worker. But a customs declaration form from 1924 proves different. He shipped from Gary to Panama a doll, presumably to a daughter and family he left behind in Panama. In 1931 Miguel marries Maria Gallegos in Chicago, a union that seemingly does not last long. No other records for Maria were to be found. At the time of his death, the male informant claims him as never married. In 1946 at the age of 55 he became a naturalized U.S. Citizen. About a decade later, he died at the age of 64 in 1955. Miguel was buried in an unmarked grave at Calvary Cemetery in Portage, Porter County, Indiana.

1924 Customs Declaration Form, courtesy of Marita Huertas

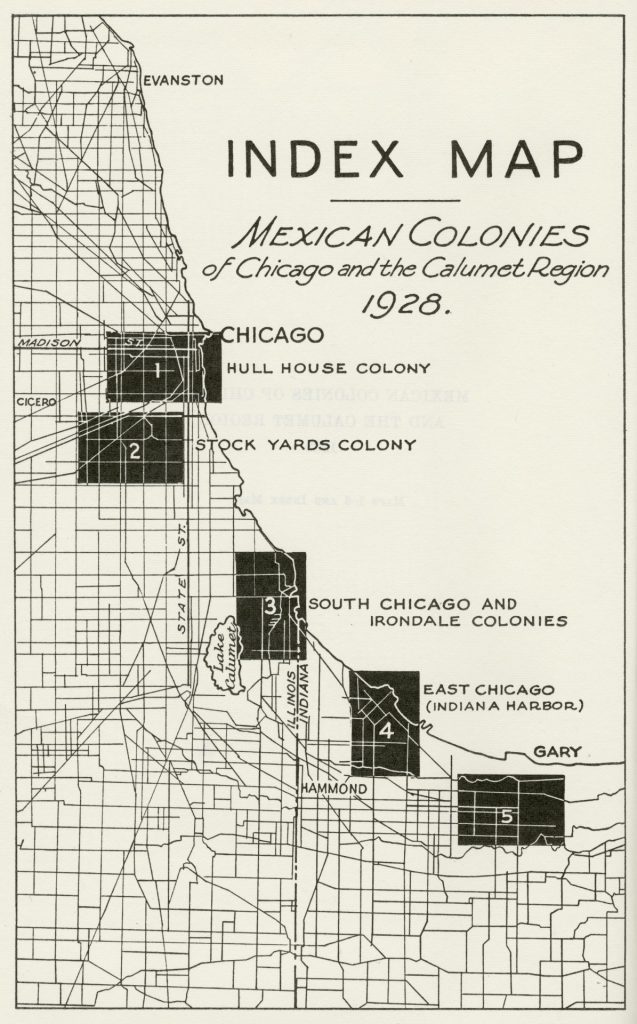

His story reminds me and us that not all Latinos in Indiana are Mexican. In 1932 economist Paul S. Taylor released volume two of his field research study titled, Mexican Labor in the United States. Looking back, this title is problematic, ignoring the possibility of other Latin American ethnicities that might be living within a large Spanish speaking, Mexican majority community. This report offers an overview of the Latino population primarily in Chicago and Northwest Indiana at the start of the Great Depression. Depression era attitudes and outlook would contribute to repatriation efforts that were explicitly labeled in area newspapers as a relief program. Latinos and Hispanics by cultural ethnicity is tricky to pinpoint on U.S. Census records prior to 1980. It was not until 1980 when appropriately worded questions were added to this decennial survey, thus making Latinos statistically invisible.

Mexican Colonies of Chicago and the Calumet Region, 1928; Source: Mexican Labor in the United States, Vol. 2 ., 1932 by Paul S. Taylor

I read the entire select batch of employment records that included Miguel’s, all 394 records. The cultural and ethnic background of those who worked alongside Miguel on the Panama Canal were from Antigua, Barbados, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Fortune Islands (Long Cay), Grenada, Guadeloupe, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, St. Johns, St. Lucia, St. Thomas, Trinidad, Suriname, Venezuela and the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and Philippines. Other countries outside of U.S. Territories, Latin America and the Caribbean were Greece, India, Italy and Spain.

The plausibility that Miguel from Peru was the only employee to move from the Panama Canal Zone to the steel mills of Northwest Indiana is minimal. In the end, not all Latinos are Mexican.