Plan your visit

The East Chicago Washington High School Walkout, 50 Years Later

October 28, 2020

On a usual day, the morning bell would start the beginning of the school day. On October 2, 1970, the morning bell would start something else for East Chicago’s Washington High School as nearly 600 students walked out of their first period class. The students, a multiracial collection of ethnic Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, African Americans and ethnic European students marched out of their classes and onto the sidewalk in front of their high school holding signs demanding the resignation of (now deceased) Assistant Principal Mitchell Baran. What had Baran done to become the focus point of this walkout? What was this protest about? Why a walkout?

East Chicago Washington High School, Anvil Yearbook 1969

Charles Johnson, who was a sophomore at Washington High School, did not remember where the idea of a walkout came from. The tactic was not new to The Region nor to the Civil Rights Movement. In Gary, Indiana, students at Froebel High School utilized the walkout to protest integration in the 1940s, drawing the attention of Frank Sinatra. However, during the 60s and 70s, in the Southwest the walkout proved an instrumental tactic. On March 1, 1968, thousands of students at schools across East Los Angeles walked out of their classrooms to protest educational discrimination in their system. The 1968 walkouts gained statewide and national attention, popularizing the tactic, particularly among urban and Latinx communities.

A few days prior to the walkout at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in Indiana Harbor [East Chicago] had asked two members of its congregation: Susan Roque and Irene Gonzalez to help enroll two young Tejanos, or Mexicans from Texas; Jesse and Gerry Arredondo. The Arredondo siblings recently moved to The Region from Texas, ahead of their parents. Roque and Gonzalez were serving as their guardians to enroll them in school for the year. When discussing with Mr. Baran about enrolling Jesse at E.C. Washington High School, the assistant principal allegedly proclaimed that, “Mexicans are lazy and ignorant.”

Recalling the incident as it was told to him, Washington Spanish instructor, Frederick Maravilla recalled that there was a miscommunication about the process of enrolling the student from out of town. He added that, as he was told, that the student lived in Gary and not in East Chicago. According to Maravilla, Roque and Gonzalez were told that they were ignorant of the process and Baran had not in fact called them, or the entire Mexican “lazy and ignorant.” Regrettably, only three people knew what was actually said and that uncertainty drives how the Walkout is remembered.

The word quickly spread around the school. Gerry Magallan, a freshman at Washington, recalled walking behind his older sister and her friend home from school. Another student of that time, Julie Cordova said she did not remember where she heard about the walkout from in the days before the protest. Johnson said that he had heard about the planned walkout by word-of-mouth from a few friends. For Johnson and his group of friends “It was like hitting home. These were kids that we knew. Why would you keep them from enrolling?”

Nearly 600 students walked out with the sound of the bell on October 2. Johnson said that he was amazed to see students of all races at the walkout. Cordova remembered that the students that walked out was a diverse cast of students. Magallan stayed in his class with Mr. Wargo and remembered that the students protesting outside were so loud that Wargo could not continue with class. Instead, he spent the period asking about the walkout and criticizing it but not without the pushback of Magallan and some of his peers.

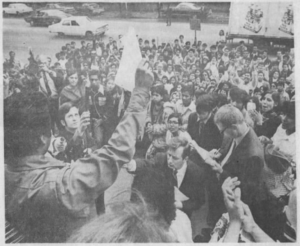

Large Latin crown bunches on the school steps to hear a spokesman announce written agreement. Article: Latins Return to Class, The Times, by. Charles Sterling

The outrage over the alleged comments did not end with the walkout. Students took over the office of School Superintendent. Outraged community members and parents demanded that their councilman, Jesse Gomez Sr. look into the matter. Gomez served as a crucial voice for the community. At the time he was the first, and only, Latino Councilman in the city, and the state. Regretfully, the report of the incident is no longer available. Students and community members would later organize on Mayor John B. Nicosia’s yard to protest Baran’s reinstatement within days of his suspension.

Students were “at home” in the superintendent’s office, Article: Latins Return to Class, by Charles Sterling, The Times, October 7, 1970

As the fiftieth anniversary approached, I posted some photos and newspaper clippings to a Facebook page dedicated to East Chicago. For some, they recalled participating and being proud to do. For others, they never knew this Walkout happened. Baran’s niece shared that a brown pick-up truck frequently drove past their house.

The 1970 walkout and ensuing protests sparked a significant turning point for the Latino community. Antonio Barreda, at the time of the walkout, was an activist and member of the community organizations, Youth Advisory Board and Twenty-Twenty. When asked about the role of the walkout for the community, Barreda replied that “It was a genesis of our community. We evolved. Coming out and saying Basta (that’s enough)!”

The walkout had many results for the community. Although Baran was not terminated, he was eventually moved to the Administration of the School City of East Chicago. Morry Barak, a freshmen during the walkout, claimed that when Robert Segovia was appointed to the school’s administration, he oversaw the most jobs in the city. Barreda noted that within Segoiva’s first year, Latinas and Latinos went from five employees to forty-three.

The walkout is important because it shows the power and resilience of a community as old as the town itself.