Purchase Tickets

A Passage to Indiana…But to Freedom?

September 10, 2020

Two years ago, the Indiana Historical Society received an unusual and distinctly unsettling gift. The real story would count among my favorites for compelling, compassionate reasons and among my bleakest for the all-too-obviously unresolved hurt and human degradation linked to its history.

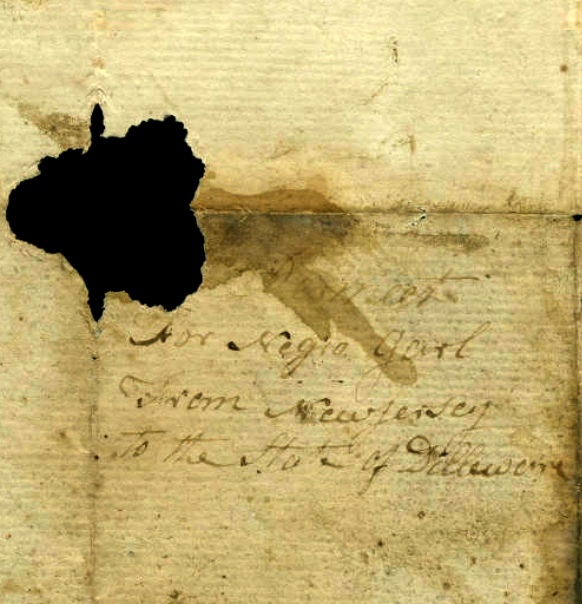

At the core of the acquisition: a travel document, legally required for an enslaved African American to be able to move (i.e., be transported against one’s will) from state to state or from region to region. The official instrument, dated 10 November 1807, was issued by the State of New Jersey not for the person whose name it bears – Chloe or “Clo” Coverdale – but for the man, Matthew Coverdale, who owned her and was empowered to make all judgments and decisions surrounding her rights, including her physical movement, and her fate.

To summarize, Chloe, a young “Negro girl…of the age of six years, or there about,” was being held in Cumberland County, New Jersey in 1807, living with the Coverdale family, and had to be transported to Sussex County, Delaware, as she was being given as property to James Huffington, Matthew Coverdale’s newest and “well beloved” son-in-law. The document literally enabled Huffington to take physical control and custody of Chloe, a little girl, to transport her to his home in Delaware, and to make her his own.

“Clo” (or “Chloe”) Coverdale was born in Delaware around 1800. On 10 November 1807, a legal document was signed by her owner Matthew Coverdale that allowed her to travel from Cumberland County, New Jersey, to Sussex County, Delaware, with James Huffington. “Clo” remained with the descendants of James Huffington’s family for her entire life, even after she received her freedom from slavery. Indiana Historical Society

That same year, a law was enacted prohibiting African Americans from reentering the state of New Jersey after a two-year absence, so her return to a place she may have considered home, and perhaps, to a mother or some family, was unlikely.

It was also in 1807 that James Huffington and Susannah “Susan” Coverdale, Matthew’s daughter, had wed, apparently prompting the transmittal of Chloe, possibly for Susan’s benefit. At that time, while New Jersey and Delaware were not large slave strongholds, such owning of other humans was readily permitted, and by 1800, the likely time of Chloe’s birth, about 5.8% of the Garden State’s populace consisted of enslaved individuals. Laws abolishing the practice would not be instituted until later, though the 1804 Gradual Abolition Act in New Jersey halted much activity and worked progressively toward abolition. In Delaware, a decline in slavery, accomplished often through manumissions begun as early as 1790, led to a vast number of slaves being freed by 1810, and with continuing vocal opposition of Quakers in the state, and a decline in the need for some agricultural labor, the influence of forced servitude was consistently and incrementally eroded. However, slavery was not completely abolished in either state, by law, until broader passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 made it so. Until then, each state had kept its own degree of slaveholding alive, though without technically being called a slave state.

Within a matter of years of Chloe being pulled away to Delaware and growing to maturity there, and with an ever-increasing intolerance in the state about the keeping of slaves in a changing environment, the Huffington family, including, reportedly, up to five of the nine children of James and Susannah, would move to Indiana, around 1831, taking Chloe, now in her thirties, with them.* It was possible to bring a slave to the Hoosier state, as, while the institution of slavery was denied in 1816 through its constitution, and an 1820 ruling in favor of a former slave’s freedom soon established Indiana as, more or less, a free state, the pre-existing ownership of slaves was tacitly permitted and upheld. It was a broad, gray area. While Indiana didn’t endorse perpetual servitude, it did little to improve the condition of those who had been held in bondage in other states, brought here against their will, and helpless to resist. Some individuals identified as slaves were still evident on both the 1830 and 1840 state censuses, while the numbers of “free” or non-slave Blacks grew into the thousands. Still others, who were brought here from states outside of Indiana, did not come as free souls, and their lives were often unchanged and in a perpetual state of limbo. This was likely true for Chloe Coverdale.

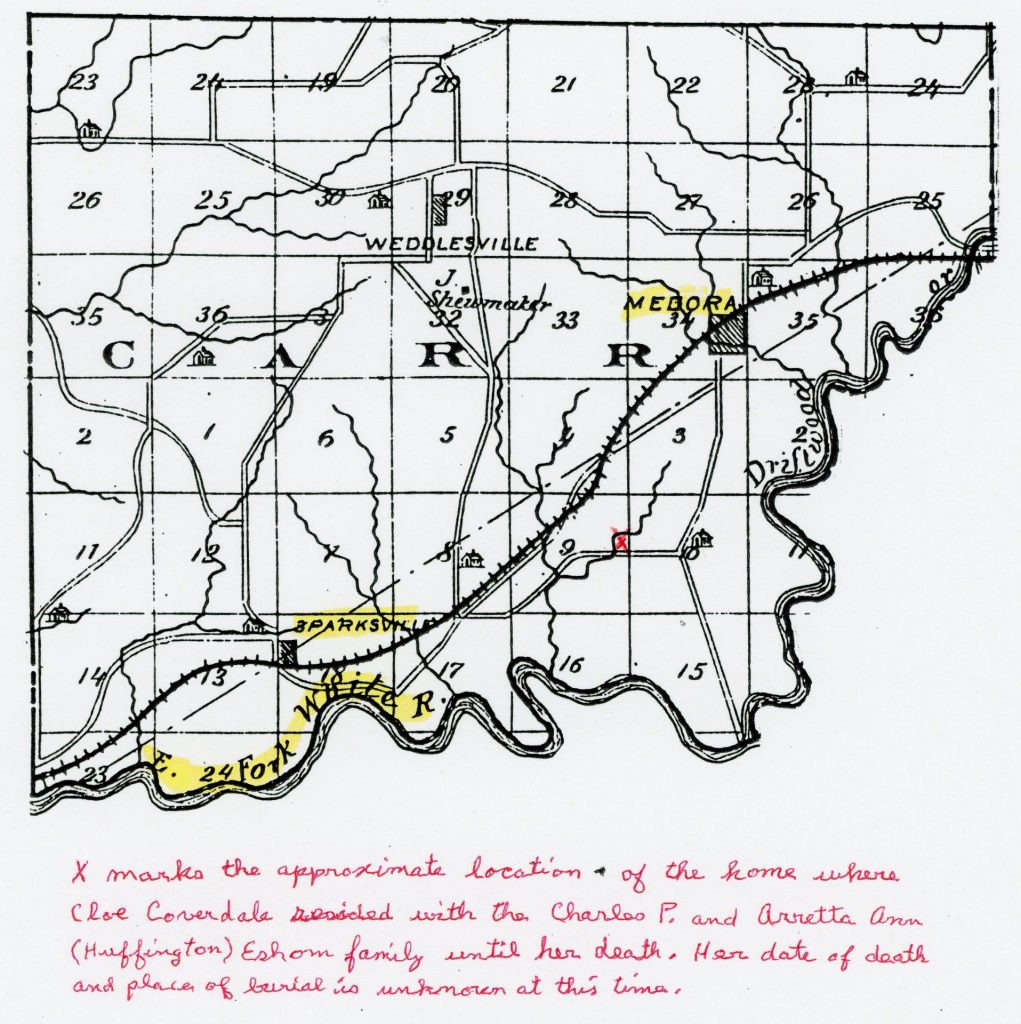

Not much has been recorded formally about Chloe’s time in Indiana, particularly in the earlier years. Such was often the case for someone whose life and human experiences were eclipsed from the historical record by slavery, leaving a sad chain of missing details. It is assumed that the woman known as Chloe, Cloe, or Clo first resided with James and Susannah until their respective deaths, and then subsequently with various other family members. The Huffingtons and many of their descendants remained chiefly within a ten-mile radius of the tri-county borders of Lawrence, Jackson, and Washington counties, spending most of their years in the remote corners of Flinn and Guthrie Townships, Lawrence County and Carr Township, Jackson County.

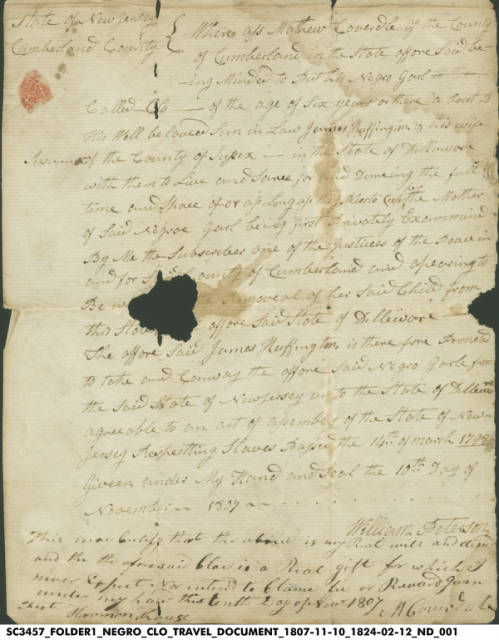

Portrait of James Madison Huffington, ca. 1870s

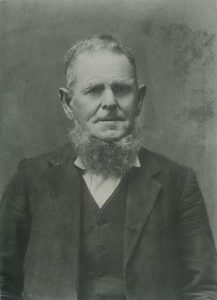

Highlighted map of Carr Township, Jackson County

With the 1840 census showing Susan Huffington evidently widowed in Jackson County and living with three of her younger children, Chloe does not appear to be recorded in her household, or perhaps any other, so she could have been sent to live with one of Susan’s adult children, perhaps given to one, or else left undocumented totally. By 1850, Chloe seems to be missing once again in that enumeration. Her first visibly verifiable place of residence in Indiana was with the James Madison Huffington (top photo) family of eastern Lawrence County in 1860. Her occupation in that census was left blank. The younger James, also known as Madison, or “Mat,” was among the older sons of James and Susannah, and had come to Indiana with his parents. It was there, in Lawrence County, that Chloe apparently remained a number of years, past the Emancipation Proclamation and even the Thirteenth Amendment, surfacing again on the 1870 census. After Mat Huffington’s wife, Eliza, had died in 1868, he swiftly remarried, and his second wife, Phoebe or Zelphia, is with him on the 1870 census, along with Chloe, who was still an adjunct part of the household.* That arrangement may have soon changed.

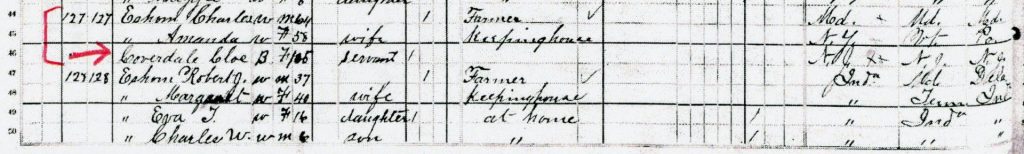

Within a fairly short time, Chloe was more or less ‘inherited,’ or at least her services were, by Huffington’s younger sister, Aritha or Arretta, and her husband, Charles P. Eshom, residing about nine miles eastward, in deeply rural Jackson County, and a little more than two miles southeast of Medora. As Arretta died by 1871, it seems likely her health may have required Chloe’s labor to assist with care of the household. By 1880, Chloe is found with Eshom and his second wife, Amanda Clark, whom he had married in 1875. In a 1904 biographical sketch of the Eshoms’ only surviving son, Robert, it says of Arretta, “that her maternal grandfather, whose name was Coverdale, gave to her mother a negro slave, named Chloe, and said slave was later presented by her owner to the latter’s son, James M. Huffington. The negress was given her freedom in Delaware, but chose to come to Indiana with the family, and she passed the closing years of her life in the home of the subject’s parents, having been more than one hundred years of age at the time of her death. She will be well remembered by many of the older settlers in the county.” One could only hope her situation was that idyllic.

1880 census highlight showing Chloe in the Eshom household.

Some of the likely sanitized statements from that county history source were that Chloe was truly free, that she came joyously to Indiana to serve her slave-owning family, and that she lived to such an imaginatively fabled age. Possibly a fraction of this was true, as she was probably no more than 85 at the time of her death. With no date of birth likely known, her age seemed to evolve and increase with each passing census, creating a more magical, charitable tale about the old ‘colored’ woman who had willingly come with her cherished and benevolent family to Indiana, and who had lived to a ripe old age.

The experience I had with Paul A. Carr, the donor of this collection, was among my most positive and fulfilling in recent memory, for not only did he possess a generosity of heart and an understanding of the Chloe document’s vital history, but he had clearly worked tirelessly and had done a yeoman’s job in piecing together as much of the storyline and supporting documentation that he could uncover with the resources available. The document and accompanying handwritten notes, recording a list of Eshom family births and a receipt from 1824, were found in the 1960s by a deer hunter and removed from an isolated, ramshackle structure in northern Washington County, possibly on a 70-acre strip of land Mat Huffington had purchased there, a short distance across the East Fork of the White River from where Chloe and the Eshoms had lived, on the opposite side, in Jackson County. The hunter then offered the papers to the care of his niece, an antique dealer in Fort Wayne, who, in turn, later gave them to Carr, after learning of his interest in local history. Hailing from the same area as the Eshoms and Chloe, Carr was well positioned to understand the historical backdrop of the story, and having acquaintance with a person who knew of his historical interests allowed him to secure the unique record so that it could be saved. To find someone who recognizes the significance of a surviving fragment of history, who takes great care in doing his homework about the item, and then contributes the manuscript out of sheer altruism is rare. It was Carr’s dedication to this study that inspired me to look deeper for any additional answers and insights.

Alas, perhaps the greatest mystery and most absorbing chapter of Chloe’s life was how it ended. What happened in her final years? How did she live? What did she think about as she aged? Was there someone she wished to see? She had surely missed the mother from whom she was likely taken, and probably had a sense of longing for any family of origin. All these questions are veiled deeply with a sense of wonder.

In Indiana, Chloe may not have been called a slave, but was she treated any differently? Chances are, her life was no better off, post-emancipation, than any servant or maid, with limited or non-existent resources, nothing she could call her own, and no way out. She may have served a family, but was she really part of the Huffington or Eshom families? As a single, older, Black, probably childless, female, she truly had no concrete options that would raise her station in life. It’s possible she remained where she was because she saw no other path and had no recourse or support for leaving her situation.

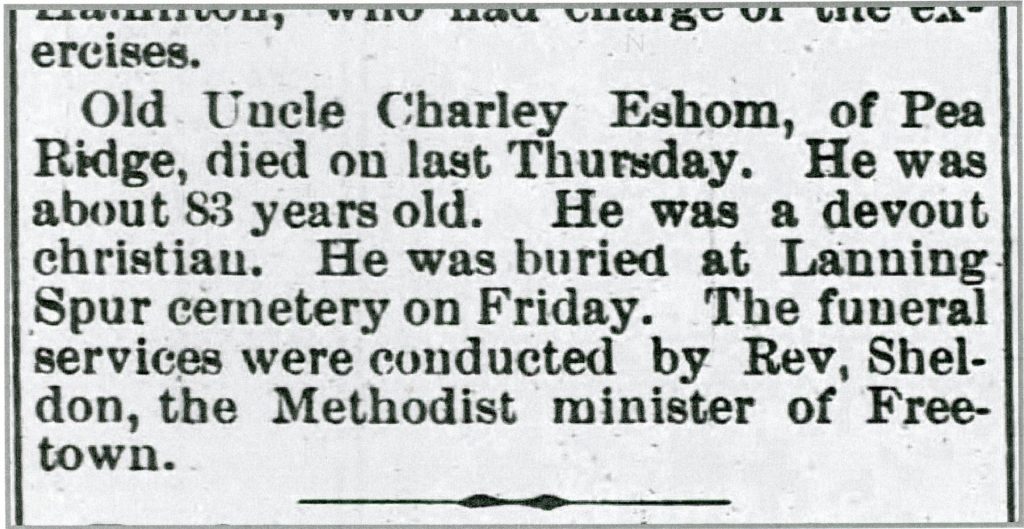

On her own, her living conditions could have been considerably substandard, perhaps in a small shelter, likely with little or no consistent heat, no running water and maybe even with a roof that leaked. At least one account infers she may have had a small room of her own in the Eshom home, a one-story, four-room 1850s clapboard structure. It’s not easy to know, especially since her travel document had been located in a shack over the border in neighboring Washington County, and what had remained of the old Eshom house was destroyed by fire around 1980. By the time Chloe’s life was drawing to a close, she had spent the preceding few years with the last of three generations of the family–Coverdales, Huffingtons, and Eshoms–that had owned or managed her. In 1880, she likely found herself situated with the widowed husband of a woman who had been the granddaughter of her original owners. And, as Charles Eshom had remarried after his wife’s death, his connection to the Huffingtons, after taking a new bride, had possibly dissipated. For Chloe to be living with an in-law of her slave-owning family and that man’s second wife was hardly an enviable position for her, and how they looked upon the aged woman’s daily care is difficult to ascertain. While Eshom’s death notices from 1897 focus on his Christian piety and his provision for his family, and a notice a decade earlier for his wife’s 65th birthday states the Eshoms enjoyed “the esteem and admiration of all who know them,” these reports came from the same newspaper, the Jackson County Banner, for which Eshom was a known subscriber. It was unlikely the paper would have depicted him in an unflattering light.

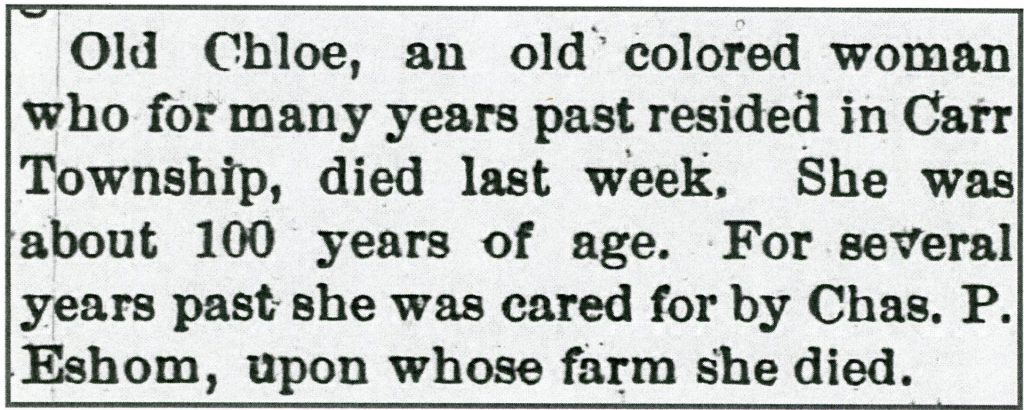

Chloe death notice in 1884

During the week when Chloe died in January 1884, Indiana was experiencing one of the coldest stretches of winter in a long time, with temperatures throughout the Midwest plunging to -26 to -30 degrees, or even lower in some locations. The state was decidedly in the deep freeze. No matter what the circumstances, it was not optimal living for an elderly, likely weakened woman. Considering her advanced age and possibly other contributing health issues, it seems altogether likely that exposure to a depth of cold so frigid easily could have hastened Chloe’s swift decline and death. The three-sentence newspaper obituary summarizing her life’s ending lent only a mere slice of perspective. It records that she was very old, colored, and had been in the care of the Eshom family. That was the apparent sum and substance of her life, as white residents saw it.

The Eshoms were buried in Lanning Spur Cemetery outside of Medora. Whether or not Chloe may have been buried there as well, or possibly elsewhere in the cemetery, is unknown. It’s almost certain her grave would have been set apart and left unmarked.

Charley Eshom obituary

Though we know far too little about Chloe, we discern something of her existence and that she had an irrefutable role in serving and caring for the family to which she had been tied her entire life. Had it not been for her travel document we would not understand as much as we do in order to form the basic structural outline of her life’s details, and we may never have learned about where she lived and when she died. Or that she existed at all. If it were only possible to discover where she is buried, I would feel compelled to take flowers, pay my respects, and avow, “You mattered, Chloe.”

_________________

*A reference on the 1830 census of Sussex County, Delaware shows only one slave, a female, age 24-35, counted under the household and property of the elder James Huffington. This would be the precise age group for Chloe, who was reportedly born around 1801. Though some of the older or adult children of the James and Susannah Huffington remained in Delaware, at least three, or as many as five, including James Madison and Arretta, came to Indiana, according to a report in a county history.

*In March 1881, Madison “Mat” Huffington, experiencing difficult times, attempted to take his own life “by opening the veins in one of his arms.” The attempt was attributed “to mental aberration, superinduced by financial misfortunes.” This occurred after Chloe had left his household to live with the Eshoms. Huffington recovered and lived on another 23 years.