Purchase Tickets

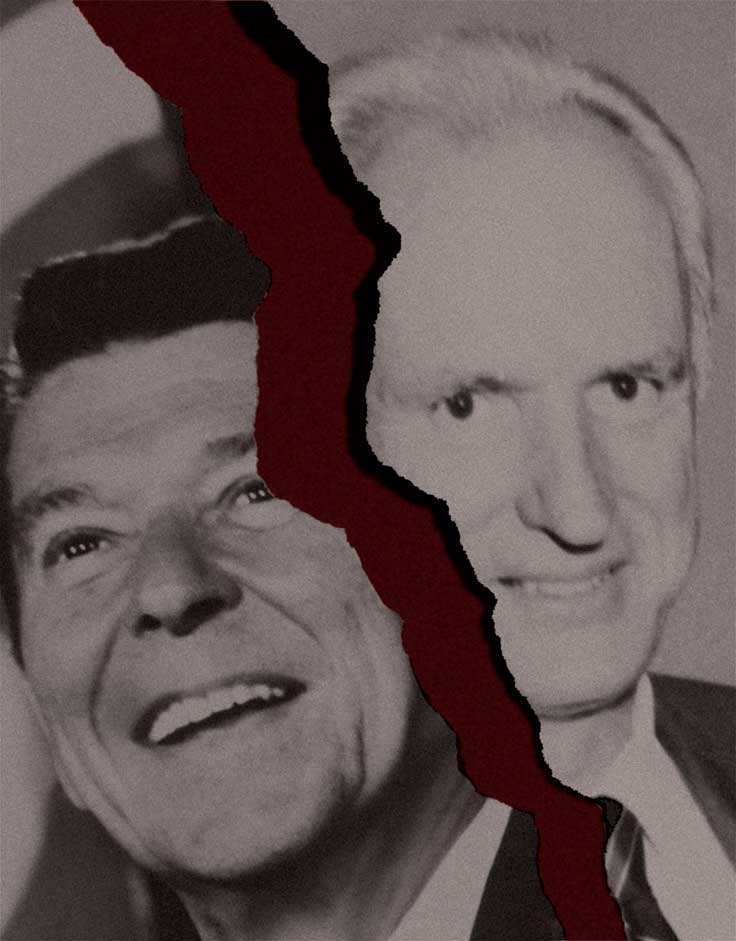

William Hudnut III Versus the Reagan Administration

From Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, Winter 2019. To receive Traces four times a year, join IHS and enjoy this and other member benefits. Back issues of Traces are available through the Basile History Market and at images.indianahistory.org.

“Either I have moved away from them or they have moved away from me”

In 1991 evangelist and motivational speaker Guy Kawasaki interviewed Indianapolis mayor William Hudnut III for his book Hindsights. After a recent failed run for Indiana Secretary of State, Hudnut did not seek re-election as mayor for the first time since 1975. Kawasaki wanted Hudnut to articulate lessons learned from his time in office. Hudnut answered with responses that were out of sync with the normal Republican rhetoric of his time, coming across as dejected with a party he had been a part of his entire political life. When Kawasaki asked about his perceived pivot from party orthodoxy, Hudnut responded: “Well I am out of step with the Republican Party on a lot of things. I think either I have moved away from them or they have moved away from me.”

How was it that after being the Republican face of Indianapolis for sixteen years Hudnut was out of touch with his own party? After all, Indianapolis was the twelfth-largest city in the country and the largest Republican-controlled city. Hudnut had economically transformed the city and as recently as 1988 had been named “Nation’s Most Valuable Public Official” by City and State Magazine and was also nationally visible as president of the National League of Cities. Hudnut’s prominent position should have led to the national stage. Instead, Hudnut was left behind as a castoff by the ultraconservatives of the Republican Party.

A moderate Republican who had lived through the Civil Rights movement and supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Hudnut’s views were at odds with the agenda of President Ronald Reagan and a Justice Department that took its cues and ideology from former Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater. The rhetoric began to dominate the Republican Party platform with the appointment of William Bradford Reynolds as the assistant attorney general in 1981. The two sides within the Republican Party were destined to collide.

What happened in Indianapolis in 1984 between Reynolds and Hudnut is a dramatic example of that collision. In this case, Hudnut publicly opposed Reynolds’s demand to modify the city’s affirmative action consent decree between the Indianapolis Police Department and the Justice Department. The episode was a key test of Hudnut’s leadership. More important, it was a battle for the very soul of the Republican Party at the local level. As more far-right conservatives pushed the Republican Party’s platform away from retaining previous urban Republican commitments of federal aid and other Great Society programs, moderate Republicans at the local level of government were forced to choose between toeing the party line and the needs of their constituents. Ultimately, this shift in party agenda, and Hudnut’s response to it, pushed him out of electoral politics and, in turn, pushed the national party further to the right.

In 1984, under the direction of Reynolds, the Justice Department’s Civil Rights division filed a motion in federal court to modify government hiring consent decrees in Indianapolis and fifty-five other cities. The targeted decrees were affirmative action hiring agreements between the city police departments and the Justice Department. In Indianapolis’s case, the consent decree called upon the IPD to more closely reflect the city’s diverse population. By demanding modification to the agreement, Reynolds aimed to effectively end affirmative action in government hiring.

On January 8, 1984, the Justice Department sent a letter to Hudnut indicating its interpretation of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision Memphis Firefighters vs. Stotts. The case held that affirmative-action goals did not need to be considered over bona fide union seniority rights when applying to layoffs. Hudnut responded that he did not interpret the Stotts decision to be relevant to Indianapolis’s specific decree and therefore had no intention of voluntarily modifying it. On April 29, 1985, the Justice Department filed a motion against the city in district court requiring a modification of the consent decree. Hudnut released a statement declaring the city would see Reynolds in court. Invoking a phrase from a popular civil rights rallying cry, he declared: “We must keep a steady course toward the future; we will not turn back after coming this far.”

As the largest Republican-controlled city in the nation, Indianapolis was an unusual target for the Reagan administration. Hudnut had maintained a close working relationship with many in the Republican Party at the federal level. He struggled to find a reason why Indianapolis was being put on the defensive. Hudnut found the demand from the Justice Department to amend the city’s specific decree absurd, going so far as to refer to it as the “injustice department.” The decision to sue the city came across like an ambush rather than a concerted effort to change party direction in the best interest of constituents. Not only did Hudnut vow to take the Justice Department to court, but he also warned the Republican Party about pushing the rhetoric of such a polarizing issue, believing it would alienate African Americans from the Republican Party.

In Indianapolis the City-County Council voted unanimously and across party lines to support the mayor’s stance. Letters concerning Hudnut’s position poured in to the Indianapolis City-County Building. Some complimented Hudnut for standing up for affirmative action and the “premise that all men are created equal,” while others praised him for his Christian values in protecting the program. Minority members of the Republican Party, some not even Indianapolis constituents, made sure to commend Hudnut on his rationality on the issue in comparison to other prominent Republicans.

Of course, not all the mail was supportive. Increasingly swayed by Reynolds’s merit-based argument, staunch conservatives saw Hudnut as turning against the party, with one writing, “Will the real Hudnut please stand up? If you are a liberal let us know, if you are a conservative, then look at this policy through conservative eyes and see the great harm it’s done.” Some refused to believe evidence of systemic oppression, asking, “Why does the city administration insist that the marketplace is prejudicial and is unwilling to select properly qualified to employ?” One person went so far as to chastise Hudnut for wanting affirmative action because Indianapolis “already had black police officers and firemen,” either not realizing or not acknowledging that by 1986 the larger African American presence on the force was mainly because of Hudnut’s affirmative-action policies.

Hudnut and Reynolds came from very different backgrounds that shaped their respective agendas regarding affirmative-action policies. Hudnut was ten years older than Reynolds, an age gap that made an enormous difference in terms of their experience with the civil rights era. Born in Cincinnati, Hudnut came from a family of Princeton University alumni; both his father and grandfather graduated from Princeton and pursued careers as ministers. Hudnut attended Union Theological Seminary and studied the importance of inclusivity in addressing social-justice issues under the tutelage of theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. After graduating with a master’s degree in 1957, Hudnut became a pastor and remained one for more than ten years before he started to become interested in a life in politics.

Hudnut was a minister when Americans were in the throes of the civil rights movement. He was deeply affected by Doctor Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and was preaching for peace and justice in its aftermath. “I cannot speak for any of you, although I hope I do,” Hudnut said after King’s death, “but I can say for myself that there is emptiness in my heart this weekend—and grief—and shame—and disgust—and fear—and bitterness—and a great deal of sadness.” As Indianapolis’s mayor, Hudnut joined only nine other cities in the country by dedicating King’s birthday a holiday. He also was the first mayor in the nation to initiate Black History Month in his community.

Hudnut came to Indianapolis in 1964 to serve as a minister at the Second Presbyterian Church, which was first served by Henry Ward Beecher. Coincidentally, Hudnut’s grandfather married a Beecher, who was a cousin of Harriet Beecher Stowe of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame. Advocacy for civil rights, it seemed, was in the mayor’s DNA. Hudnut, like Beecher, sought to use his pulpit as a platform for change. He did not just preach, but was actively involved in the Indianapolis community. He gave sermons at churches around the city, including African American congregations. He made a point to volunteer at the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Marion County Mental Health Association and was familiar with most of the problems facing the inner city. He used his role in politics as an extension of his role as minister in that it was another way to serve the community.

In 1975 Hudnut decided to run for mayor and won. From the onset of his tenure in office, he attempted to address IPD hiring discrimination. He acknowledged the minority discrepancy problems in 1977 in one of his first speeches as mayor. “In our city, the disparity between the proportion of black officers on the Indianapolis Police Department and the proportion of black citizens in the Police Service District is glaring: 11 percent versus 22 percent,” he noted. “Slowly that gap must be closed. It will only be done as a strong recruitment is mounted in the black community and as qualified blacks in greater numbers compete with whites for the few slots that open each year.” By 1984 Hudnut had been mayor for almost a decade and was intimately aware of the city’s needs. He genuinely believed in affirmative action and what it was meant to do for Indianapolis’s African American community.

Beatreia Burgess, age eight, receives an award from Hudnut during a Youth Service Sunday. (Indianapolis Recorder Collection, Indiana Historical Society)

Reynolds, who proudly traced his lineage to the Pilgrims, took a much different path into national politics. His mother, a DuPont of the DuPont industrial company, was a member of one of the wealthiest families in the Mid-Atlantic region. He was educated in boarding schools and graduated with a history degree from Yale University. After becoming editor of the law review and graduating second in his class at Vanderbilt University, Reynolds went straight into corporate law with the prestigious firm of Sullivan and Cromwell.

In 1970 U.S. Solicitor General Erwin Griswold asked Reynolds to join his staff. Reynolds remained in his office for three years before returning to a private firm in the Washington, D.C., area. He was only experienced in a few civil rights cases before coming to the Justice Department in 1981. Attorney General William French Smith admitted that Reynolds had no desire to be in the Civil Rights Division, opting instead for the Civil Division, in which he specialized. Smith saw Reynolds’s inexperience as an advantage, however, because he had the chance to influence Reynolds’s views. Likewise, Reynolds had no known objectionable stance available for congressional leaders and civil-rights advocates to oppose. Smith’s successor, Edwin Meese, opposed Reynolds’s appointment, citing his lack of experience in civil rights. Reynolds rightfully acknowledged his inability to relate to civil-service attorneys moved by a “mission” to advocate for civil rights. He once told a reporter that he did not realize civil rights was such an “emotional subject.”

With Reynolds, the Justice Department sought to move the courts to adopt color-blind language to the Civil Rights Act, which they believed allowed only “merit-based” equal opportunity, not group preferences. Reynolds argued that affirmative action as it was being applied was allowing a person’s individual rights to supersede another person’s based on race alone. This application was to him in di¬rect opposition to the purpose of the Civil Rights Act, especially Title VII, which prohibited employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sex, race, color, national origin, and religion.

Reynolds and Hudnut could not be further from each other in their opinions on civil rights, yet they were both staunch Republicans. The hallmark of a Reagan conservative was to follow an absolute ideology and let the chips fall where they may. Hudnut was less comfortable issuing absolutes without considering the consequences affecting his city. “The danger in absolutism is the complete identification of a political position with the Divine,” he warned. Some of his earliest sermons in the 1960s reflected his sentiment that it was not productive to divide people, calling instead for empathy, love, and understanding as a way to reach a middle ground. “Instead of slipping to the extremes, where there is death,” said Hudnut, “the way of love is the way of patience and understanding; of listening and hear¬ing, of dialogue and communication.”

For Hudnut, leadership entailed a consensus in deciding difficult issues: he thought reflexively and opposed strict ideology. Upon meeting with Reynolds in 1985 to discuss the implications of Stotts, he remarked that Reynolds struck him as “being a rigid doctrinaire ideologue who had no sensitivity to the problems of governing a community and only cared about pushing his conservative views.” The battles Hudnut faced were not mere intellectual abstractions, rather, they were daily realities. Furthermore, affirmative action was an institution by 1984. Even if Hudnut was in agreement with Reynolds, there existed no clear road for an urban mayor to end the program.

Indianapolis’s consent decree took almost five years to complete and had been implemented for another five years by the time Reynolds filed suit against the city in 1984. The sudden demand to dismantle all the work Hudnut had fought for simply at the behest of a new administration demoralized the mayor, who believed it was wrong for Reynolds to attempt to wipe out a policy that was decades in the making over his specific interpretation. Reflecting on the episode in 1988, Hudnut recalled, “The destabilizing influence of putting local government on this kind of yo-yo was considerable.”

Since 1968 Marion County had consistently voted Republican in the general election. In the 1980 and 1984 presidential election, Reagan carried greater Indianapolis by a 10-percent margin. Nationally, Reagan won the majority of the top 100 highest-populated counties in the country in both elections. Despite this party support in urban areas, the Reagan administration continued to cut federal programs that aided large cities. Reynolds’s lawsuit was a culmination of Hudnut’s frustrations about Republicans at the national level. To Hudnut, the suit was a realization of the administration’s intent to dismiss urban areas, departing from what he believed to be the central mission of the GOP.

Reynolds’s quest, however, ended anticlimactically. The Justice Department was forced to drop the consent decree suit against Indianapolis in 1986 after two Supreme Court cases effectively invalidated Reynolds’s efforts. The Supreme Court upheld the validity of consent degrees in Firefighters vs. Cleveland and upheld affirmative action hiring goals in Sheet Metal Workers vs. EEOC [Equal Employ¬ment Opportunity Commission]. The ruling specifically stated that the goals of affirmative action to increase minority participation did not violate Title VII. After the decision came down, Reynolds accused Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan Jr. of misinterpreting the Fourteenth Amendment with his “radically egalitarian jurisprudence.” Criticizing the decision, Reynolds also noted: “Nothing threatens our civil rights and political liberties more than a theory that sees their protection as the result of the benevolence of any public official or any particular institution of government.”

Hudnut won the affirmative-action argument in Indianapolis, but overall the Republican Party moved toward Reynolds’s brand of conservative absolutism. Reynolds resigned his position with the Justice Department in 1988 to pursue opportunities in commercial litigation. Since then, he has largely remained out of the political spotlight. He addressed the direction of affirmative action in federal policy occasionally in the 1990s on various panels, but only to restate and defend his positions and arguments from his time with the Reagan administration.

Hudnut won the Indianapolis mayoral election in 1988, his last in the city he helped rise from a community known as “India-No-Place” to national prominence. Fallout from his support of affirmative action affected his 1990 bid for Secretary of State. Hudnut’s campaign slogan stated boldly: “A Vote for Bill Hudnut is a Vote for Equal Opportunity.” His campaign focused on reminding voters that he stood up to the federal government in support of affirmative action. His message of equality, however, was not well received with the growing Republican base that was becoming more rigid in its ideology. Hudnut’s refusal to toe party lines on affirmative action had some Indiana delegates openly questioning whether or not he could continue to call himself a Republican.

Although not the only Republican foe of the Reagan administration in 1984, Hudnut made himself one of the most visible. Hudnut stated in 2016 that the key for a successful city was to “foster a city of civility and collaboration.” The strict Republican ideology that Reynolds presented was in contrast to Hudnut’s personal convictions on what he deemed “Republican.” Even if the conservative ideology made sense on paper, Hudnut believed it did not help govern, it aimed to divide. For Reynolds, the context of the law and how he believed it was meant to be applied was the only thing that mattered. For him, moral convictions were not appropriate to apply to the law. Both men insisted, however, that they were the heirs to the Republican Party.

What is clear is that the GOP moved away from moderate positions and party members such as Hudnut. The choices that remained for Hudnut and other moderates at the end of the Reagan administration were to fade out of prominence while still questioning party goals or fall in line. Hudnut made it clear: he would not be swayed just for electability, but he did leave Indianapolis. He continued to be concerned about urban issues after he moved to Washington, D.C., in 1996 to serve as a board member for the National League of Cities. He also worked for the Urban Land Institute from 1996 to 2009. His last run at public office was on the town council in Chevy Chase, Maryland, where he was selected as mayor in 2004 and served until 2006, as a Republican.

Hudnut died on December 18, 2016, after arguably one of the most partisan Republican platforms in modern memory had been written. The current administration of President Donald Trump may not be directly a result of the type of conservatism associated with Reynolds, but nevertheless remains far from the moderate Republicanism associated with Hudnut. For now, Hudnut’s career remains an outlier of remembrance for moderate Republicans who aimed to effectively govern their local communities by implementing bipartisan solutions under a policy of “come, let us reason together.”

Tiffany Costley received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in American political history at the University of Indianapolis. She is now studying law at Indiana University’s Robert H. McKinney School of Law. This is her first article for Traces.

For Further Reading

William H. Hudnut III Collection. University of Indianapolis Civil Leadership and Mayoral Archives, Indianapolis, IN. | Hudnut, William III, and Judy Keene. Minister Mayor. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1987. | Kabaservice, Geoffrey. Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, from Eisenhower to the Tea Party. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. | Smith, William French. Law and Justice in the Reagan Administration: Memoirs of an Attorney General. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1991. | Wolters, Raymond. Right Turn: William Bradford Reynolds, the Reagan Administration, and Black Civil Rights. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1996.