Purchase Tickets

Irish Immigrants in the Hoosier Hills

From The Hoosier Genealogist: Connections, Fall/Winter 2018. To receive Connections twice a year, join IHS and enjoy this and other member benefits. Back issues of Connections are available through the Basile History Market.

Large numbers of Irish immigrants began coming to America in the early eighteenth century. Many who made the voyage before the American Revolution came from the northern province of Ulster and were Presbyterian. They entered the country through such places as Philadelphia and Charleston, migrated to the western fringes of the colonies, and settled the rural areas of Appalachia.(1) This largely Presbyterian emigration continued after the Revolution and remained an important part of the Irish exodus until the 1830s. By that time, though, Irish Catholics, especially from the southeastern province of Leinster and the southwestern province of Munster—but also from Ulster—had joined the outflow in increasing numbers. In the middle and later decades of the nineteenth century, Catholics came to heavily dominate Irish immigration to America, and most of them settled in towns and cities of the Northeast and Midwest.(2) This created the impression, still in evidence in some historical work, that the Catholic Irish, in spite of having a rural background in Ireland, became an urban people in America and had almost no impact on the countryside of their adopted land.(3)

More recent historical studies have shown that this was not the case; Irish Catholics established many successful farming communities across the country during the nineteenth century. The stories of some of these communities are now available to us including, for example, those of the Irish families who settled in various rural pockets in the Northeast, especially in parts of upstate New York.(4) Irish immigrants took to farming in several well-defined Irish rural communities in the Midwest too, most remarkably, perhaps, in Beaver Island, Michigan, but also in many locations in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois.(5) In the Plains, too, we encounter Irish Catholic farming communities, especially in parts of Iowa, Kansas, and the Dakotas.(6) Such settlements were less common in the southern states, although a remarkable one emerged in the countryside around Refugio and San Patricio, Texas.(7) Remarkable, too, was Locust Grove, Georgia, the childhood home of author Flannery O’Connor’s great-grandfather that was established by Irish farmers from County Tipperary and was also the inspiration for author Margaret Mitchell’s “Tara.”(8) Finally, several scholars, including most recently David Emmons, have revealed and described a rich mosaic of nineteenth-century Irish immigrant communities, many of them engaged in farming, throughout the far West.(9)

Irish Catholic immigrants settled down to farm in parts of Indiana as well. I became personally aware of a cluster of those communities in the southwestern part of the state quite by accident some years ago. The area in question is in the eastern part of Daviess County andthe adjacent western fringe of Martin County, lying roughly between the towns of Washington and Loogootee. It is largely centered on the small town of Montgomery. The Irish settled in a total of eight contiguous townships here, lying both to the north and south of US 50 in southwestern Indiana.

I became aware of these communities while on a tour of the Amish country in the Washington–Loogootee area one autumn afternoon in the 1990s. I began to pay particular attention to the numerous Catholic cemeteries in the area and was especially surprised to see many Irish surnames on the headstones. The first of these was Saint Michael, near Plainville, several miles due north of Montgomery; others included Saint Peter in Montgomery and Saint Mary in Barr Township, just northwest of Loogootee. There are many Irish immigrants’ graves in the latter two cemeteries (as was specified on their headstones), most of whom were born in the late-eighteenth century or in the first two or three decades of the nineteenth century. For me, knowing as little of the history of the locality as I did at the time, this was a surprise and a mystery. What were these natives of Ireland doing in the middle of “Amish country,” and how did they get there in the first place?

That mystery deepened when I later visited the cemeteries at Saint Patrick in Corning and Saint Patrick in Glencoe, both near the Glendale State Fish and Wildlife Area in the far southeast corner of Daviess County. In these two cemeteries, located in the beautiful hill country of southern Indiana, the nineteenth-century graves were almost all of Irish natives and included many from County Wexford, home of my ancestors. Among those buried in Glencoe were several members of a family named Donnelly/Donnolly, some of whom came from the little country parish of Kilmuckridge where my mother’s family lived in the nineteenth century and where they still live today. As a professional historian who normally tries to avoid becoming emotionally involved in my subject, I permitted myself an emotional moment in a field close to Glencoe’s cemetery one sunny afternoon a few months later. By that point, I knew that the Donnelly family had become farmers in this corner of the Hoosier state and that the field in which I was standing had been part of their Indiana farm. I realized that my ancestors in their little Irish parish would have known these Donnellys and would have remembered when they left for America. I wondered to myself whether anyone else from Kilmuckridge had ever visited them or their descendants in all the intervening years since they left Ireland. My conclusion (convenient perhaps in terms of my desire to tie the story together) was that no one had and that here I was, nearly two hundred years after they had left, doing just that. The looping together of our worlds—our ancestors’ worlds and our modern one—is made possible by modern travel and modern access to research materials, making such convergences no longer a distant dream. There were no Donnellys there anymore to greet me (a family named Doyle lived on the farm at the time), but since then I have met a descendant and shared some laughter and a few tears at the thought of all the pain associated with the story of the Irish diaspora. We shared, too, a few expressions of admiration for those people who, with their fellow immigrants, put a distinctive stamp on this little patch of southern Indiana.(10)

Who then were these Irish immigrants who came to live in southeastern Daviess County and in the western townships of Martin County? Perhaps the first general comment we can make about them is that they originated in the same three Irish provinces from which most Irish immigrants, including most Catholics, came to America in the decades prior to Ireland’s Great Famine of 1845 to 1849.(11) The burial records from the cemeteries in Daviess and Martin Counties, for example, reveal that out of the 180 Irish natives whose county of origin is specified, 99 (or 55 percent) came from the eastern province of Leinster, 43 (or 24 percent) from the northern province of Ulster, and the remaining 38 were from southern Munster Province and western Connaught Province in approximately equal numbers (around 10.5 percent each). Those from Ulster came largely from counties in the central part of that province (especially Derry/Londonderry and Tyrone), and those from Leinster came largely from the southern half of the province, especially from Wexford and Kilkenny, the two counties that occupy the southeastern corner of Ireland.(12) The pattern might be considered typical for the time, although the large component from Wexford and Kilkenny is somewhat unusual and resembles more the pattern of migration to eastern Canada than to most parts of the United States.(13)

The men and women of these various parts of Ireland made their way to Indiana by a wide array of paths. The local tradition in Daviess County is that they had worked on the Wabash and Erie Canal, which was dug through this part of the state in the late 1840s and early 1850s, but the historical evidence actually suggests that, even though many did come into the area as canal workers, the earliest Irish arrived well before that period. Those pre-canal Irish joined an already established Catholic settlement that had its inception here early in the nineteenth century when some French Catholic settlers established a small community at Black Oak Ridge on the western fringe of present-day Montgomery. The French established Saint Peter Church in Montgomery in 1818 (making it the second oldest Catholicparish in the state).(14) They were joined in those early decades of the century by families of Maryland Catholic origin. The ancestors of these families came from England and settled in Maryland in the seventeenth century. Their descendants crossed the Appalachians in the 1780s and settled in Kentucky, and their children in turn joined the exodus of settlers from the Bluegrass state into southern Indiana in the first two decades of the nineteenth century.(15)

The first members of what would become the Irish Catholic population of Daviess County appear to have arrived in 1821 when three brothers—John, Michael, and Denis Murphy—settled in the small town of Liverpool (later to be renamed Washington). Located about seven miles west of Saint Peter Church, the town was no more than a small cluster of log cabins on the Louisville–Vincennes Road, which ran through heavily forested country at the time. Irish immigration had been at a standstill in the first fifteen years of the nineteenth century (due to the disruption of shipping caused by the Napoleonic Wars), and people like the Murphys would have been in the first wave that entered the United States after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. They were not unique among Irish immigrants in venturing this far west at such an early date. Another Irish family, the Lawlers from County Kildare, had already made their way down the Ohio River in 1819 and begun what would turn into another largely Irish Catholic farming community at Equality, in southeastern Illinois, a few miles northwest of Shawneetown, Illinois.(16)

Two of the Murphys enjoyed considerable success and prominence in their adopted home in the years that followed. Daviess County land records reveal multiple purchases made by John and Michael Murphy during the 1820s and 1830s. John bought two lots in the frontier town the year he arrived (for $50) and later made additional purchases. Michael bought a town lot in 1825 (for $40), and a year later he bought several more lots worth a total of $300. Records show Michael continued to purchase land into the 1830s.(17) These two Murphy brothers were spectacularly successful in financial terms; at the end of their lives, both left large legacies after their debts were accounted for: $30,000 in John’s case; and $20,000 in cash and stocks in Michael’s.(18) As an example of the pre-famine Irish immigrant experience, they demonstrated a remarkable degree of success, and their story suggests the extraordinary level of opportunity small settlements on the Indiana frontier afforded those who had the means to take advantage of them. Given how quickly they did so, it is likely that the Murphy brothers came to America with the capital and education that could facilitate such a rise.

Other Irish families joined the Murphys in Daviess County during the latter half of the 1820s. Though none of them experienced quite the level of success two of the Murphy brothers enjoyed, many established themselves firmly among the farming population of the area. One of the first of these was a native of County Wexford named William Molloy (spelled “Meloy” on his headstone). Wexford had been the center of the 1798 Irish Rebellion against British rule, an event that would have shaped the experience of many of the Irish who settled in this area.(19) Wexford was also one of a block of Irish counties in the southeastern part of the country that had been English-speaking for several centuries and that enjoyed a well-developed economy by the standards of the time. A second such English-speaking area lay in the eastern half of the province of Ulster, and it is perhaps not insignificant that many of the Irish who took up farming in Daviess and Martin Counties in the nineteenth century came from both of these regions.(20)

William Molloy was born in Wexford around 1780, so he may have fought in 1798. His wife, Margaret, was also a native of Wexford. The couple arrived in Daviess County in the 1820s and settled in Sugar Creek Hills, an area of rolling hills in northern Harrison and northernReeve townships. Molloy was in his forties at the time, old for a pioneer settler, and that may explain his nickname “Grandad.”(21) He did not buy land until 1840, but prior to that time he may have either worked as a hired hand or tenant farmer. Coming from nineteenth-century Ireland, he would have been very familiar with tenant farming. Molloy’s farm was close to Glencoe.(22)

Two other Irish Catholics, John Toy and Phfelix Bradley, both of whom were from the province of Ulster, arrived in the Sugar Creek Hills shortly after Molloy. Toy came from County Tyrone in the central part of Ulster and reached the northern part of Harrison Township in 1827. Like Molloy, he did not buy landimmediately but eventually purchased a tract about a mile northeast of Molloy’s.(23) Bradley also likely arrived in 1827 and established his family on a farm in southern Barr Township, a few miles south of Saint Peter Church. He was from Maghera Parish in County Derry/Londonderry, a locale where the Bradley name was common. A cluster of several families with that surname occupied land near the village of Maghera in the early nineteenth century, and Phfelix is likely to have been a member of that kin group.(24)

Irish families continued to move into the area south and east of Saint Peter in the 1830s at a modest but steadily increasing rate. The new arrivals included James Kelly, Patrick Doran, John Riley, and the wives who probably accompanied them. In 1831 Kelly bought 80 acres of land in the middle of Barr Township near the Louisville–Vincennes Road for $300, a price that suggests both the value of land in the location and also the considerable resources that this immigrant had at his disposal. In 1832 Doran (a name that suggests a Wexford origin) bought 139 acres in eastern Washington Township, and in the same year, Riley bought 80 acres in northeastern Barr Township and added another 80 acres in the same township a year later.(25) Meanwhile, Francis Bradley, whoHILLSmay have been Phfelix Bradley’s son, bought 80 acres, just west of Saint Peter, near the Louisville–Vincennes Road for $425.(26) Another Bradley—Patrick, who emigrated in 1832 (and may have been following his relatives from Maghera to this corner of America)—also acquired land in Barr Township by 1850.(27)

The Irish Catholic population in eastern Daviess County was small but noticeable to outside observers by the mid-1830s. One of those outsiders was Bishop Simon Bruté of Vincennes. In 1836 Bruté decided that the Catholic population living in the eastern fringe of Barr Township was large enough to justify establishing a log church so the settlers in the area would not have to make the journey all the way to Saint Peter on Sundays. He went out himself to join the local priest, Simon Petit Lalumiere, in the task of consecrating the new structure, which became Saint Mary Church in Barr Township. His report on the occasion sheds light on the population that lived roundabout and is a wonderful description of the deep religiosity of this little part of frontier Indiana:

On the day appointed all the good people assembled with the pastor, Fr. Lalumiere, at the little chapel. It was built of logs, as almost all the buildings still are in this part of the country. It is only about from fifteen to twenty years since these settlements were made. There are about 150 families, most of them from Kentucky, but some from Ireland. We formed a procession and went around the chapel and the ceremonies were observed as closely as possible; then I celebrated mass and gave an instruction to those who were present. Some baptisms and a marriage filled up the labors of the day, marked as the first on which I blessed a church in the wilderness.The conduct of the people was full of edification.(28)

This description of the occasion suggests that the Irish component of this rural Catholic population, while discernible, was fully incorporated into the social fabric of the area. By the end of the 1830s, then, eastern Daviess County was home to two Catholic churches—Saint Peter (Black Oak Ridge) and Saint Mary.

Irish settlers continued to arrive. The 1840 census records suggest that at least twenty-two Irish families were living in Barr, Harrison, and Reeve Townships at the time. Since this census did not specify country of birth, however, this may have been an undercount.(29) Land records also suggest a surge in Irish Catholic land acquisition in the area in the late 1830s, a surge that intensified in the early 1840s. A search by last name in the deeds index for the county suggests that while only one Irish family bought land in the late 1820s, twenty-nine families did so in the decade from 1830 to 1839, and a total of fifty did so between 1840 and 1846. This was a substantial leap over the earlier periods.(30)

Naturalization records suggest the same pattern. Thus, of the ninety-five Irish natives who filed for citizenship in Daviess County between 1817 and 1850, ten had immigrated between 1821 and 1830, and sixty-six had done so between 1831 and 1840. Given that Irish Catholics who acquired farms in the United States usually worked in various non-farm occupations before settling down to till the soil, this suggests that many of the Irish of Daviess County likely arrived there in the 1830s or in the early years of the 1840s. This would make the population largely pre-famine in origin, arriving in America prior to the outbreak of the potato blight in 1845 and certainly before the peak of the famine exodus from Ireland took place between 1847and 1852. This group also would have arrived before the peak of the canal-digging project in the area, which took place between 1847 and 1853, almost exactly corresponding to the years of the famine exodus.(31)

The gradual increase in the Irish farming population of the area in the late 1830s and early 1840s led to the emergence of a largely Irish district in an area embracing the southern fringes of Barr Township, the northern third or so of Reeve Township, and the northeastern quarter of Harrison Township. In response to this, the Catholic church established a mission chapel at Glencoe in 1840 named after Saint Patrick and sited roughly in the center of the Irish settlements in those three townships. This church became the religious center of the Irish living and farming in Sugar Creek Hills for the next thirty years and was also the site of a cemetery and a school.(32) This signified the degree to which a large part of the southeastern quarter of the county was then settled by Catholic farmers of various national origins, with the area around Saint Patrick in Glencoe being almost completely Irish.

By what path, then, did these Irish families make their way to rural Daviess and Martin counties? Most, it would seem, landed in ports in the mid-Atlantic states and made their way directly westward over a period of several years through Pennsylvania and Ohio to Indiana. Though there were exceptions—a few moved to Indiana from southern states and also from New England and eastern Canada—the birthplaces of children born to these farmers between their departure from Ireland and their arrival in Indiana strongly suggests that this was the usual pattern. Thus, of the 151 children born by 1850 to Irish farmers who lived in Daviess and Martin counties, a total of 63 were born in the mid-Atlantic coastal states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. Only 9 were born in Canada or New England, 4 in southern states with an Atlantic coastline (Virginia and South Carolina), and 4 in Gulf Coast states (Mississippi and Louisiana). The other 71 children were born in the non-coastal states of Ohio, Kentucky, and Illinois. This evidence suggests a relatively direct westward migration path from mid-Atlantic landing points, a pattern consistent with work on major road, canal, and railroad projects at the time.(33)

The general pattern outlined above conceals the stories of individual family migrations, however, and several of these offer remarkable examples of the complexity of the journey and the resiliency of the immigrants themselves. Three families who settled in the vicinity of Saint Mary and Saint Peter—the Nolans, Cunninghams, and Grannans—provide interesting illustrations of how different the process could be for the families involved.

The Nolans came from or near the town of New Ross in County Wexford and settled in Daviess County in the early 1840s. New Ross had a long-established seafaring tradition and had an especially strong connection with what would be the Canadian maritime provinces of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. The Nolans in Daviess County seem to have followed two brothers, Patrick and James, born in the vicinity of New Ross in 1814 and 1821, respectively. Patrick emigrated sometime in the 1830s and by September 1840 was in Green County, Ohio, where he filed for American citizenship. He was twenty-six years old at the time and may have been working on a canal. By 1847, he was living in Daviess County and was granted citizenship there that year. His brother James left Ireland in the spring of 1841 and landed in New York. He moved west to Ohio quickly and was in Daviess County by that December, a rapid transition from first arrival in the United States to settling in Indiana that probably occurred because he was joining a kinsman already settled on a farm.(34)

Michael Cunningham was born in 1814 or 1815 in County Roscommon just as the Napoleonic Wars were ending. Both of his parents died when he was young, and he and his sister were raised by an uncle. He began working in Roscommon at the age of sixteen, and by the time he was twenty-one (in 1836), he had saved enough money to bring both himself and his sister to the United States. They landed in New York City where Michael worked for a time digging cellars, then moved to Rhode Island where he worked on a railroad, and then moved back to New York where he worked construction jobs in the city. In 1838, just two years after arriving in America, the Cunningham siblings went south to Mobile, Alabama, but left soon after because of an outbreak of yellow fever. Next, they headed north again, making their way up the Mississippi River and living for a time in Chicago, Illinois. Michael worked on riverboats for seven years, mostly on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. In 1840 he visited friends, presumably Irish immigrants, in Daviess County, Indiana, and they persuaded him to buy land there. He purchased 160 acres in Barr Township, very close to Saint Mary Church. He visited his farm every year, gradually improving it and readying it to become his permanent home. He finally settled there in 1843 and a few months later married Julianna Shircliff.(35)

The Grannans came from Lissoy, County Westmeath, and County Longford, and were led to America in 1830 by Bridget Grannan, a widow. Bridget and her children reached Daviess County in the middle of the 1830s, and her son Bernard bought 120 acres in Barr Township in 1837. A year later he married Margaret Bradley, one of the Bradleys of Maghera and probably Phfelix’s daughter, and settled down to life as both a farmer and a millwright. Other members of the family acquired land in Daviess County, too, and by the middle of the century, they owned several large farms.(36)

The Irish who settled on farms in the area around Glencoe included several individuals with equally interesting histories. William Donnelly, the native of County Wexford who may have known my family back in Ireland in the early nineteenth century, was born in 1805. The tithe record from Kilmuckridge, which was probably his native parish, includes only one family with that last name in 1833, and they were farming seven acres of land in the townland of Ballinlow on the estate of the Bruen family, the local landlords, at the time.(37) Donnelly left Ireland with his family in 1822 when he was seventeen years old and sailed to Upper Canada. He worked as a laborer in Canada for two years and then in 1824 took a ship across Lake Ontario to Oswego, New York, and entered the United States. Over the next twelve years, he lived what he later remembered as “an unsettled life.” It is likely that he worked on canals in upstate New York for a time (the Erie was under construction when he arrived in the Empire state), and he seems to have been in Kentucky in the mid-1830s. He got to Daviess County in 1836 and acquired land in northern Harrison Township, not far from where his fellow Wexfordman, William Molloy, was living and close to James Toy. He would eventually acquire almost two hundred acres. His wife, Mary Molloy, whom he married in 1834, was also a native of Wexford and was probably Molloy’s daughter.(38) There is some chance, therefore, that the two families, the Donnellys and Molloys, may even have known each other in Ireland.

Another arrival who settled in the general vicinity of Glencoe was Michael Shea, a native of the Catholic parish of Windgap, in County Kilkenny near the western border of County Tipperary. Shea seems to have come from a more substantial background than did William Donnelly: the only Shea family in the parish of Windgap at the time of the tithe survey was a tenant on twenty-four acres (in the townland of Knockroe). Shea left Ireland in 1833, at the age of twenty-two and sailed from Liverpool to Philadelphia. After working there for a year, he moved to New York City and made his way west to Indiana in 1838. He bought land and settled in northern Reeve Township in 1840.(39)

John Jones, a native of County Wicklow who settled on a farm near Michael Shea in northern Reeve Township, had what was probably the most remarkable journey of all. He was born in 1809, immigrated to England when he was in his early twenties, and worked in a soap factory there for six months. Jones left England for Quebec in 1832 when he was twenty-three years old and worked for a few months on farms in Canada before entering the United States at Oswego, New York, following the same path William Donnelly had taken about a decade earlier. He worked on a farm near Oswego for a short time and then moved west and worked on the Wabash and Erie Canals near Fort Wayne, Indiana. Jones eventually left canal work and became part of the crew on a flatboat on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in the late 1830s. He worked on riverboats of various kinds into the early 1840s, moving frequently between New Orleans, Louisiana; Mobile, Alabama; and Cincinnati, Ohio. During that time, Jones also worked occasionally on railroads. Eventually, in 1850, this remarkable rambler married a recently arrived Irish immigrant girl named Mary Gallagher in Cincinnati, and the couple moved to Daviess County, Indiana, bought land in Reeve Township, and settled down to farm.(40)

In sum, the story of Irish immigration to Daviess and Martin Counties provides a fascinating glimpse of Indiana’s complex immigration history. Here, in the center of a region where German, Swiss, and French immigrants were numerous, we find Irish Catholics settling on farms and building rural Irish Catholic communities. These Irish immigrants came primarily from the provinces of Leinster and Ulster and began to arrive in the area well before the Great Famine and before the canal project in this region was underway. The paths they took across the United States ran mostly from the mid-Atlantic states straight west, although their stories include some tales of extraordinary travels before they eventually arrived at their Hoosier homes. They acquired farms in significant numbers in the 1830s and early 1840s, and by the time of the 1850 census, they had created the foundation of a viable and long-lasting Irish enclave in the heart of the southern Indiana countryside.

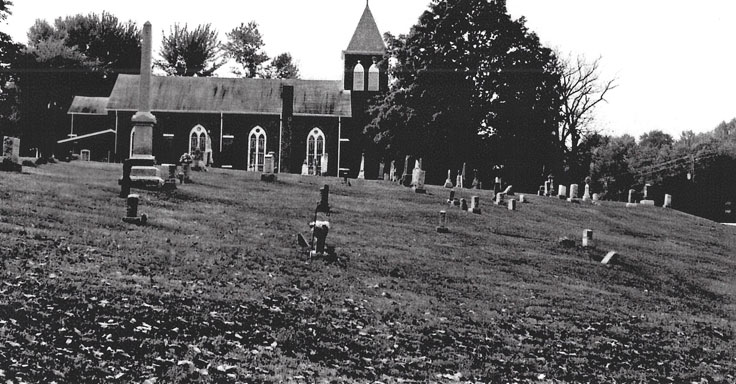

Image: Saint Patrick Catholic Church Cemetery in Corning, Indiana, holds many graves of Irish immigrant farmers. (Photo by Maria Gahan, 2004)

Part 2 of this article will appear in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of THG: Connections. It will explore the kind of community the Irish immigrants of Daviess and Martin Counties built by 1850 and how the community evolved over the second half of the nineteenth century.

Notes

1. Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 137–68, esp. 137, 161–68.

2. Ibid., 193–235, esp. 193; Marianne S. Wokeck, Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to North America (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 167 219; Miller, Emigrants and Exiles, 345–53.

3. For a lively discussion of the emphasis of historians on urban Irish American Catholics, see Donald Akenson, BeingHad: Historians, Evidence, and the Irish Exodus to North America (Port Credit, ON: P. D. Meany Publishers, 1985); and “An Agnostic View of the Historiography of the Irish Americans,” Labour 14 (Fall 1984), 123–59.

4. For a good example of an Irish American farming community, see Daniel J. Casey and F. Daniel Larkin, “From Dromore to the Middle Sprite: Irish Rural Settlement in the Mohawk Valley,” Clogher Record 12, no. 2 (1986), 181–91.

5. Helen Collar, “Irish Migration to Beaver Island,” Journal of Beaver Island History 6 (1976), 27–50. On the Irish in Wisconsin, see Grace McDonald, History of the Irish in Wisconsin in the Nineteenth Century (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1954); for the Illinois story, see Paul Gates, The Illinois Central Railroad and Its Colonization Work (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934; repr., New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1968), 89ff.

6. Kenneth P. Smitz, “Father Thomas Hore and Wexford, Iowa,” The Past: The Organ of the Ui Cinsealaigh Historical Society, 11 (1975–1976), 3–20; Peter Beckman, The Catholic Church on the Kansas Frontier, 1850–1877 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 1943), 70; David Kemp, The Irish in Dakota (Sioux Falls, SD: Rushmore Publishing House, 1992).

7. Graham Davis, Land! Irish Pioneers in Mexican and Revolutionary Texas (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2002).

8. David T. Gleeson, The Irish in the South, 1815–1877 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 30; Kieran Quinlan, Strange Kin: Ireland and the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005), 4, 118–19; Sarah Gordon, A Literary Guide to Flannery O’Connor’s Georgia (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2008), 48.

9. David Emmons, Beyond the American Pale: The Irish in the West, 1845–1910 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010); R. A. Burtchell, “Irish Property-Holding in the West,” Journal of the West 31, no. 2 (1992), 9–16.

10. For a more detailed account of my encounter with Daviess County andthe traces of the Irish there, see Daniel Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley: Irish Catholic Settlement in Daviess County, Indiana, 1821–1850,” in The Wexfordman: Essays in Honour of Nicky Furlong, ed. Bernard Browne (Dublin, Ireland: Geography Publications, 2007), 89–134. Thomas Donnolly of Kilmuckridge is discussed on page 127.

11. S. H. Cousens, “The Regional Variation in Emigration from Ireland between 1821 and 1841,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 (1965), 15–30, esp. 18.

12. Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 97–99. Irish county of origin is specified on these 180 gravestones. FindAGrave.com contains images of many gravestones of individuals mentioned in this article as well.

13. John J. Mannion, Irish Settlements in Eastern Canada: A Study of Cultural Transfer and Adaptation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974), 19–20.

14. Herman Joseph Alerding, A History of the Catholic Church in the Diocese of Vincennes (Indianapolis: Carlon and Hollenbeck, 1883), 87–90, 251; L. Rex Myers, Daviess County, Indiana, History, vol. 1 (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing, 1988), 195; The Short History of St. Peter Catholic Church, St. Peter Catholic Church, http://stpetermont.org/St.%20Peter%20Short%20History.html, accessed October 2018.15. Gregory Rose, “Hoosier Origins: The Nativity of Indiana’s United States-Born Population in 1850,” Indiana Magazine of History 81, no. 3 (September 1985), 201–32; Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 103; A. O. Fulkerson, ed., History of Daviess County, Indiana: Its People, Industries, and Institutions (Indianapolis: B. F. Bowen and Co., 1915), 196.

16. The History of Knox and Daviess Counties, Indiana (Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing, 1886), 675, 726; Miller, Emigrants and Exiles, 193–95; For the Lawler family story, see J. T. Dorris, “Michael Kelly Lawler: Mexican and Civil War Officer,” Journal of the Illinois Historical Society 48, no. 4 (Winter 1955), 366–401.

17. Evidence of land purchases made by the Murphy brothers can be found in the Deed Index of Grantees, Daviess County, Indiana, Recorder’s Office, courthouse, Washington, Indiana. Some examples follow: Deed of Sale, William Chapman to John Murphy, July 16, 1821, Deed Book A, vol. I (1817–1852): 279–80; Deed of Sale, Amory and Hannah Kinney to John Murphy, August 8, 1827, Deed Book B, vol. I (1817–1852): 338; Deed of Sale, Thomas and Sarah Teming to Michael Murphy, October 29, 1825, Deed Book B, vol. I (1817–1852): 119; Deed of Sale, Amory and Hannah K[i]nney to Michael Murphy, November 10, 1826, Deed Book B, vol. I (1817–1852): 199. Twodeed of sale records for land purchased by Michael Murphy in 1832 appear in Deed Book C, vol. I (1817–1852): 100. For an example of John Murphy’s prominence in the community, see History of Knox and Daviess Counties, 612. John was a member of a committee established in Washington, Indiana, in 1841 to oversee the construction of the new county courthouse.

18. Will of John Murphy, October 25, 1873, Will Records, Daviess County, Indiana, vol. I (Sept. 1854–June 1887): 287–90; and Will of Michael Murphy, Decem-

ber 4, 1876, Will Records, Daviess County, Indiana, vol. I (Sept. 1854–June 1887): 426–27, in Recorder’s Office, courthouse, Washington, Indiana. Each Murphy brother’s “legacy” is an approximate total value derived from each brother’s will by summing all financial bequeaths and bond values listed and subtracting all listed debts.

19. Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 106, 127; For the most comprehensive recent compendium of work on the Irish Rebellion of 1798, see Thomas Bartlett, David Dickson, Daire Keogh, and Kevin Whelan, eds., 1798: A Bicentennial Perspective (Dublin, Ireland: Four Courts Press, 2003).

20. On the geography of language in nineteenth-century Ireland, see Garrett Fitzgerald, “Estimates for Baronies of Minimal Level of Irish-Speaking amongst Successive Decennial Cohorts: 1771–1781 to 1861–1871,” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 84C (1984), 117–55, esp. 127.

21. Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 106, 127. The Molloys’/Meloys’ gravestones in the cemetery at Saint Patrick of Glencoe, Indiana, attest to their origins in Wexford. History of Knox and Daviess Counties, 593.

22. Deed Index of Grantees, Daviess County, Indiana, vol. I (1817–1852), Recorder’s Office, courthouse, Washington, Indiana. There are several deed of sale records indexed here, identifying William Molloy’s land purchases; Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 127.23. Deed Index of Grantees, Daviess County, Indiana, Deed Book E, Vol. I (1817–1852): 96–98. John Toy bought 80 acres in two tracts in Section 23/2/6 in September 1840; Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 125; History of Knox and Daviess Counties, 593.

24. Myers, Daviess County, Indiana, History, vol. 1, 281; Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 106–7, 123; 1831 Ireland Census for Phfelix Bradley, Maghera, Londonderry, National Archives of Ireland, available at http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels

/c19/007246495/007246495_00126

.pdf, accessed October 2018. It seems likely that Phfelix Bradley and his wife, Mary, are the leaders of the Bradleys mentioned by Myers. They would be the parents of Margaret and, therefore, also likely the “Mr. and Mrs. Bradley” mentioned in Margaret (Bradley) Grannan’s obituary from August 28, 189[9]. According to the obituary, in an unknown Washington, Indiana, newspaper, her family first came to Maryland and Ohio before settling in Indiana in 1827.

25. Deed of Sale, Elisha and Mary Perkins to James Kelly, February 25, 1831, Deed Book C (1817–1852): 73. Kelly’s land was in Section 20/3/1. Deed of Sale, John J. Eleanor O’Brian to Patrick Doran, April 14, 1832, Deed Book C (1817–1852): 385–86. Doran’s land was in Section 5/2/7. Deed Book C (1817–1852), page 77 contains two deeds of sale for land purchased by John Riley in 1832 and 1833. Riley’s land was in Section 2/3/5.

26. Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 106–7, 123; Deed of Sale, John and Rachel Shepard to Francis Bradley, November 17, 1834, Deed Book C (1817–1852): 310. Bradley’s land was in Section 22/3/6.

27. The author researched abstracts of naturalization records from Daviess County on index cards at the Washington, Indiana, Public Library. The original records were apparently housed in the clerk’s office in the county courthouse in Washington, consisting of the orders written in order books for the county’s courts. For more information aboutwhere to find naturalization records in Indiana see the Foreword in An Index to Naturalization Records in Pre-1907 Order Books of Indiana County Courts (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 2001), v–vii. This book also contains indexed data for the naturalization records found in this article. Subsequent notes will indicate “Name of individual (Patrick Bradley in this case), Naturalization Records Abstracts, Washington Public Library.” 1850 U.S. Census for Patrick Bradley, Barr Township, Daviess County, Indiana, family no. 1211, National Archives microfilm M432_140, page 171B, digitized by Family Search, available on Ancestry.com. Emigration from Derry/Londonderry was at an unusually high level in the 1820s and 1830s. See David Fitzpatrick, “Emigration,” in Ireland Under the Union, Volume 1: 1801–70, vol. 5, A New History of Ireland, ed. W. E. Vaughan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 620.

28. Alerding, History of the Catholic Church in the Diocese of Vincennes, 252.

29. Fulkerson, History of Daviess County, 195–97. The 1840 U.S. Census for Daviess County, Indiana, is accessible online through Linkpendium at http://www.linkpendium.com/daviess-in-genealogy/cen/. The records, provided by My Heritage, are browsable by township, which brings up links to an alphabetical list of names of heads of household in the census. The 1840 census does not record place of birth. However, the 1850 census does record country (or state) of origin. Working with knowledge of those names can help in determining country of birth for the 1840 census.

30. Deed Index of Grantees, Daviess County, Indiana, vol. I (1817–1852), Recorder’s Office, courthouse, Washington, Indiana. Calculations are based on the last names of families known to be of Irish origin.

31. Naturalization Records Abstracts, Washington Public Library; James Shannon, Catholic Colonization on the Western Frontier (New York: Arno Press, 1976), 125–33; William W. Giffin, The Irish, vol.1, Peopling Indiana (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2006), 34–36.

32. Daviess County Interim Report (Indianapolis, IN: Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana, 1987), 62, part of Indiana Historic Sites and Structures Inventory, digitized online by Indiana University–Purdue University, Indianapolis, University Library, http://ulib.iupuidigital

.org/cdm/ref/collection/IHSSI/id/12411, accessed October 2018; B. N. Griffing, Atlas of Daviess County, Ind.: From Actual Surveys under the Direction of B. N. Griffing (Philadelphia: Griffing, Dixon and Co., 1888), 53. A map of Harrison Township shows a Catholic church, cemetery, and school in the location where Glencoe’s Saint Patrick Cemetery is found today.

33. 1850 U.S. Census for Madison, VanBuren, Barr, and Reeve Townships, Daviess County; and McCameron, Brown, Perry, and Rutherford Townships in Martin County, available on My Heritage through Linkpendium (see note 29 above). The 1850 census recorded place of birth, be that the various states or the nation of origin. Of the 63 Irish children born in mid-Atlantic coastal states, 37 were born in Pennsylvania, 10 in New York, 10 in Maryland, and 6 in New Jersey. Of the 71 children born in the non-coastal interior, 55 were born in Ohio, 14 in Kentucky, and 2 in Illinois. See also Peter Way, Common Labor: Workers and the Digging of North American Canals, 1780–1860 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), xiii–xvii.

34. Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 124; John Mannion, “A Transatlantic Merchant Fishery: Richard Welsh of New Ross and the Sweetmans of Newbawn in Newfoundland, 1734–1862,” in Wexford History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County, ed. Kevin Whelan (Dublin, Ireland: Geography Publications, 1987), 373–421; James Nolan, Naturalization Records Abstracts, Washington Public Library.

35. History of Knox and Daviess Counties, 812–13.36. 1850 U.S. Census for Barnard Grannon, Barr Township, Daviess County, Indiana, microfilm roll M432_140, page 157B, image 150, available at Ancestry.com; Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 107, 113, 125–26; Myers, Daviess County, Indiana, History, 281.

37. Tithe Applotment Records, Patrick and Catharine Donnoly, 1833, Kilmuckridge, Wexford, Ireland, Book 95, http://titheapplotmentbooks.nationalarchives.ie/reels/tab//004625684/004625684_00509.pdf, accessed October 2018. A townland is a subdivision of a parish. In the days before standardization of measurements, there were actually a number of different types of acres, including the English, Plantation/Irish, Cunningham, and so on. All these were different in area. The Tithe Book reports that the Donnolys in Kilmuckridge worked 5 acres, 1 rood, 10 perches, or about 5 5/16 Irish acres, which works out to roughly 7 statute acres—the acre predominate in the United States and more broadly since the international standardization of units. For more information, see J. H. Andrews, Plantation Acres: An Historical Study of The Irish Land Surveyors and His Maps (Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 1985); and “Measurements,” University of Nottingham: Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham.

38. William Donally, Naturalization Records Abstracts, Washington Public Library; Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 111–12, 127. Mary is listed in the parish register for Saint Patrick of Glencoe, Indiana, under her married name Donnolly, directly below that of William Donnelly, who is indicated as her husband. William Meloy and his wife Margaret are also listed in this parish register. The register shows that all four came from County Wexford. History of Knox and Daviess Counties (pp. 593, 862–63) provides a general overview of Donnolly’s journey to Indiana, whereas the naturalization records reveal more details, though there are no significant discrepancies.

39. Tithe Applotment Records, James Shee, 1833, Tullahought, Kilkenny, Ireland, Book 101, http://titheapplotmentbooks.nationalarchives.ie/reels/tab//004625728/004625728_00302.pdf, accessed October 2018. It is assumed that Michael Shea was the son of James Shea since Michael’s naturalization record shows that he came from Windgap Parish, and James was the only Shea/Shee listed in this parish (Michael Shea, Naturalization Records Abstracts, Washington Public Library); Gahan, “From Kilmuckridge to the White River Valley,” 112, 123–24, 126. In Ireland, there are multiple types of parishes including civil, Church of Ireland, and Catholic. For more details, see “What Is a Parish?” in Ireland XO News, Ireland XO Reaching Out, https://www.irelandxo.com/ireland-xo/news/what-parish, accessed October 2018; and “Understanding Irish Land Divisions,” DoChara: Insider Guide to Ireland, https://www.dochara.com/the-irish/roots/land-divisions/, accessed October 2018.

40. History of Knox and Daviess Counties, 877–8.

Daniel Gahan is professor of history at the University of Evansville, Indiana. He spent his early life in England and Ireland and came to the United States in 1977. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the National University of Ireland, a master’s from Loyola University of Chicago, and a doctorate from the University of Kansas. He has taught at Evansville since 1986. His teaching and research interests focus on Europe in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, with special emphasis on the impact of the French Revolution on Ireland. His book, The People’s Rising: Wexford 1798 (1995), looks at the Irish rebellion which was inspired by events in France in the 1790s.