Purchase Tickets

Hoosier Confederate: The Civil War Experiences of Henry Lane Stone from Putnam County

From The Hoosier Genealogist: Connections, Spring/Summer 2019. To receive Connections twice a year, join IHS and enjoy this and other member benefits. Back issues of Connections are available through the Basile History Market.

Henry Smith Lane (1811–1881) of Crawfordsville, Indiana, was a lawyer, banker, and politician during the nineteenth century. First associating with the Whig Party upon entering politics, Lane became involved with the newly formed Republican Party in the mid-1850s. Lane assisted in the organization of the party in the state of Indiana, serving as both president of the party’s state convention and chairman of the national convention in 1856. He also served as a delegate at the party’s national convention in 1860, 1868, and 1872. Lane served as a United States senator from 1861 to 1867, being elected to the position after serving only three days as Indiana’s governor. As a senator for the majority of the 1860s, Lane worked during one of the most contentious times in American history: The Civil War. (1)

Lane supported the Union during the Civil War, as did the Republican Party. However, he was not an abolitionist. Lane held loyalty to the United States and was more concerned with slavery’s expansion into new territories and states outside of the South than with the destruction of the institution. He believed his party’s mission was “to restrict slavery to its present limits; to give the free Territories of the United States an everlasting heritage of Freedom and free institutions.” While he did not care about slavery’s continued existence in the South, Lane desired to keep the country’s new additions free. His beliefs were considered moderate within his party, and Lane considered Republican abolitionists extremists. (2)

While Lane’s pro-Union views were shared by those within the Republican Party, as well as with many in Indiana, some individuals within Lane’s family instead supported the Confederacy. One such person was Lane’s nephew and namesake, Henry Lane Stone. Stone fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War, opposing the views of his Union-supporting uncle and choosing allegiance to Kentucky, his state of birth, over Indiana.

Henry Lane Stone

Henry Lane Stone was born on January 17, 1842, in Bath County, Kentucky. He was the son of Sally Lane (1816–1909) and Samuel Stone (1797–1873). Both of Stone’s parents were born and raised in Kentucky, and after their marriage on February 8, 1821, they remained in Kentucky for thirty years. (3) At the time of Stone’s birth, his mother’s older brother and his uncle, Henry Smith Lane, was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. (4)

In his memoir, written late in life, Stone states that the family moved to Putnam County, Indiana, in 1851. Census records support this statement. The 1850 U.S. census records the Stone family living in Bath County, Kentucky, while the 1860 U.S. census places the family in Putnam County, Indiana. (5) The reason for the family’s move is undocumented. It is likely that the family moved north to central Indiana due to Lane family connections. Henry Smith Lane lived north of the Stone family’s residence in neighboring Montgomery County. Another of Sally’s brothers, Higgins Lane, also lived in Putnam County. (6)

Once in Indiana, nine-year-old Henry Lane Stone continued his education. He attended classes in public schools and later an academy in Bainbridge. In 1859 Stone became a teacher and taught in the Putnam County public schools, primarily near Bainbridge. During this time, he began studying law. In spring 1862, Stone was admitted to the bar and became an attorney in the Putnam County Circuit Court. (7) However, in fall 1862, Stone left both Putnam County and Indiana and headed south to support the Confederate States of America by joining their armed forces.

Why Stone supported the Confederacy instead of the Union during the Civil War is not clear. By the beginning of the war, Stone had lived the majority of his life in Indiana, meaning that Stone only had young childhood memories of Kentucky. While he might have had romanticized recollections of his birth state, Stone’s early adult years in Indiana were more recent and perhaps should have made a stronger impact on him. As well, many of Stone’s immediate family members supported the Union, including two brothers, Valentine H. Stone and Richard French Stone, and his mother, Sally. (8)

Sources state that Stone’s father, Samuel, sympathized with the Confederacy and supported states’ rights. Being born and living the majority of his life in Kentucky, specifically Bath County, Samuel did have strong ties to the state. In addition, Samuel served Kentucky and its people in many capacities prior to moving to Indiana, including in the Kentucky state militia (1816–1846), as Bath County state representative (1824–1836), and as magistrate and then sheriff in Bath County (1823–1841). (9) These years of military and political service undoubtedly strengthened Samuel’s allegiance to Kentucky. While the majority of Samuel’s service occurred prior to his son Henry’s birth, Samuel’s influence as a father perhaps shaped Stone’s Confederate loyalties during the Civil War.

Another potential contributing factor to Stone’s sentiments toward the Confederate cause could have been his own childhood experience with slavery. The Stone family owned slaves while living in Kentucky. According to the 1840 U.S. census, two years prior to Stone’s birth, five slaves were living in the Stone household: three men between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-five, one woman between ages twenty-four and thirty-five, and one woman between ages ten and twenty-three. The 1850 U.S. census, only one year prior to the family’s move to Indiana, shows the Stone family owning seven slaves: five men ranging in age from eleven to seventy and two women between the ages of thirty-six and seventy-five. (10) Growing up in a slave-owning household no doubt would have shaped Stone’s perspectives on slavery, most likely normalizing the institution in his mind. Additionally, moving from a slave state to a free state would have presented conflicting viewpoints, potentially leading Stone to hold onto his childhood experiences and beliefs rather than change his perspective.

Fighting for the Confederacy

While fighting for the Confederate States of America, Henry Lane Stone wrote letters to his family, primarily his parents back home in Putnam County. In this correspondence, Stone kept his family up-to-date on his current activities, health, and whereabouts. Also mentioned in the letters are consolations to his mother and confident remarks about the current and impending success of the Confederate military and its cause. (11)

Stone began his journey south on September 18, 1862. He traveled with a friend until reaching Cincinnati, Ohio, where the friend was imprisoned for suspected Confederate loyalties while attempting to leave the city. Stone continued traveling by foot and later by boat, making sure to avoid Union troops along his route. He arrived at his destination of Bath County and stayed with family until enlisting in the Confederate States of America’s military on October 7, 1862. (12) Stone served as a sergeant major of “the Second Kentucky Battalion of Cavalry, under Major [Robert] Stoner, in Gen. John H. Morgan’s Brigade.” (13)

John Hunt Morgan and his men were infamous during the Civil War. While highly respected in the South, they were feared by Union supporters and civilians. The men burned, pillaged, and stole during their travels, wreaking havoc in the towns in which they stopped. They frequently stole horses. With the many miles the group covered each day, their horses tired out quickly, and stealing new ones along the way allowed them to continue at a rapid pace. Since stealing horses was a common practice of both sides, this strategy prevented Union troops from getting the horses first, potentially giving them an advantage over the Confederates. (14) While Stone never mentions stealing any horses in his letters, he does describe in detail some of his own plunders: “I captured a splendid overcoat, lined through and through, a fine black cloth undercoat, a pair of new woolen socks, a horse muzzle to feed in, a [Enfield] rifle, a lot of peuter [sic] plates, knives and forks, a good supply of smoking tobacco, an extra good cavalry saddle, a halter, and a pair of buck-skin gloves, lined with lamb’s wool; also a pretty little cavalry hat, with a yellow wire cord around it.” (15)

Morgan is most well-known to Hoosiers for his raid into Indiana and Ohio in July 1863, in which Stone participated. This campaign included some of the few Civil War battles fought on Union soil. Morgan and his men crossed the Ohio River into Indiana beginning on July 7, and completed their crossing by the evening of July 8. (16) Stone sent his father a letter shortly after arriving back on Hoosier soil, stating “I am here with Gen. Morgan’s Command, which is now crossing the Ohio into Hoosier.” While Henry writes that he hopes the Confederates will come far enough north to allow him to visit with them, he includes a warning: “Wake up old Hoosiers now. We intend to live off the Yanks hereafter.” Stone was confident in General Morgan’s ability to organize his men and impart a serious blow on the Union on their own ground. (17)

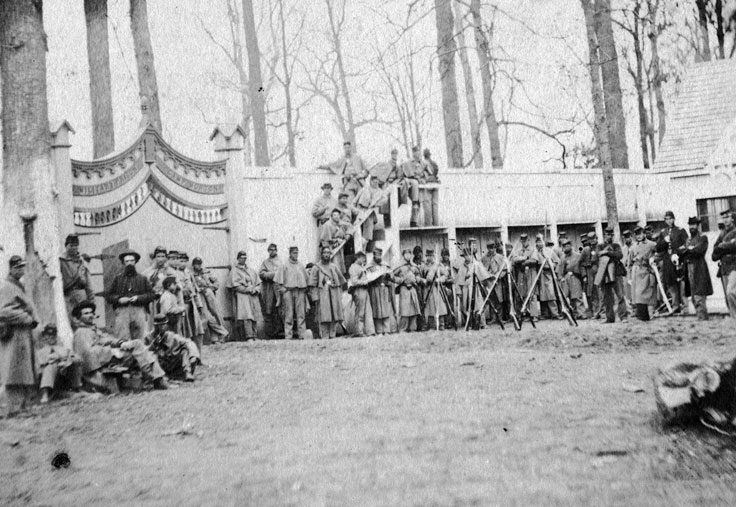

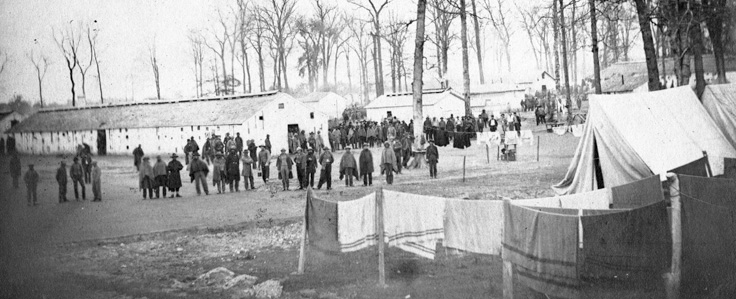

This and the featured image at the top capture life at Camp Morton on the north side of Indianapolis, ca. 1864–1865. Camp Morton was a Civil War POW camp named in honor of Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton that was operational from 1862 to 1865, housing approximately 1,600 Confederate soldiers throughout its existence. Henry Lane Stone was a prisoner at Camp Morton after being captured in 1863, along with fellow Confederate soldiers under General John Hunt Morgan’s command. In 1868, three years after the war ended, the Stair Fair was held on the site of the former camp; the event was held there every year until 1891. (Photo from Eugene F. Drake Camp Morton Photographs, P 0388, Indiana Historical Society. Information from Hattie Lou Winslow and Joseph R. H. Moore, Camp Morton, 1861–1865: Indianapolis Prison Camp [1940]; and Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 1850–1880 [1965].)

From the beginning of the raid until late July, no letters were received from Henry Lane Stone by his parents. On July 21, 1863, Stone broke the silence: “I am now, with 700 others of Morgan’s men, a prisoner of war.” Stone and his comrades were taken captive near Buffington Island, Ohio, on July 18. Stone explains, “The rest of Gen. Morgan’s Command got away . . . but whether they’ll succeed in getting entirely away I can only say, ‘I hope so.’” Morgan and the rest of his men, however, were captured after surrendering on July 26, just days after Stone’s imprisonment. (18)

Stone did not regret his capture nor his allegiance to the Confederacy as he wrote to his parents, “Don’t think I am regretting the past. As sure as a Merciful God lets me live I intend to fight the Yankee’s till victory crowns the Red, White & Red.” (19) Even after capture, Stone remained loyal to the Confederacy.

As a prisoner of war, Stone traveled extensively throughout the late summer and early fall of 1863. He and those captured with him in Ohio, were sent first to Cincinnati and then by train to Indianapolis to be held at Camp Morton, a prisoner-of-war camp on the city’s north side. While at the camp, Stone saw family and friends, some as soldiers working at the camp and others as visitors. Also, he was interviewed for an article published in the Republican-affiliated newspaper, the Indianapolis Journal. In the article Stone is reported to have inquired about “his Democratic friends in Greencastle,” and to have applauded their work “opposing the Government.” He is also quoted as stating, “The Democracy had done a great deal to aid the Confederate cause, but the best way to aid it was to fight for it.” (20) Stone’s statement helps explain why he decided to become a Confederate soldier: fighting was the most effective method for supporting the Confederate States of America, not remaining at home and opposing the Union through political efforts.

After a few weeks at Camp Morton, Stone sent a letter to his brother Jim, writing, “We have left Camp Morton, and have now established ourselves within the walls of Camp Douglas.” Stone goes on to describe the trip between Indianapolis and Chicago, where Camp Douglas was located: “We came over from Indianapolis in the night, till we got far above Lafayette; where daylight came upon us, revealing the prairies, which were beautiful indeed. At Michigan City I got my first view of a lake. The sight was very attractive. We got to see but little of this City the prison being rather between Michigan City and Chicago, though it is right in the suburbs of the latter place.” (21)

Stone was imprisoned at Camp Douglas until October 16, 1863, when he escaped. He returned to Bath County without being caught along the way. However, in November, he was captured in his ancestral home and imprisoned again, as he explained by letter: “The last time I was taken prisoner, I was at Jim Lane’s, ‘the old home stead.’” Stone was taken to Mount Sterling, Kentucky, and then, while being transported to another location, he escaped again. He attempted to return south to rejoin the Confederate military, but finding it impossible to evade Union troops, Stone chose instead to flee and went north to Canada to avoid recapture. He took the train from Paris, Kentucky, and traveled through Cincinnati, Toledo, and Detroit before reaching the American–Canadian border. (22)

Escape to Canada and the End of the War

Stone was not the only Confederate soldier or sympathizer in Canada. He estimated, in the town in which he was living, “about thirty of Morgan’s men are here. Rebels, Yankee deserters, and Draft Runners fill this town.” (23) Noting that Canada, being a separate country, was free from United States laws and military force, many individuals who refused to support the Union or the war could remain safe across the border. Stone also noted that individuals in Canada proudly expressed their allegiance to the Confederacy: “Our boys register their names here as soldiers of the C.S.A. I wrote mine so in full.” (24)

During his time in Canada, Stone engaged in a variety of activities. He expressed his hope that he could continue his study of law independently. (25) He also made “segars” (cigars) with fellow Confederate comrades, planning to expand tobacco production if he remained in Canada for an extended period of time. (26) To help pass the time, Stone fished and went squirrel hunting, observing “[Squirrels] are fully as black as the hearts of those infernal Yanks, I’ve shot at before now, and hope to again.” (27) Even while removed from the conflict, the war and his loyalty to the Confederacy were on Stone’s mind.

Stone remained confident in the Confederacy while in Canada. In a letter to his brother Jim, he proudly viewed his Confederate allegiance as an honor, concluding, “How glad I am that I can say I’ve been a consistent man, and an honorable son of the South. My military career is unspotted; I’ve never yet faltered in my duty, on the field, or in camp, or prison.” (28) However, even with this pride, Stone felt it necessary to defend his Confederate loyalties to his father, who thought Stone’s escape to Canada was wrong: “Father, when you look over my career in the past eighteen months, do you feel that I am a traitor? Have I not done my duty, and have I not followed your teachings of right? Do you feel that I’m unworthy to be your son? God forbid! My conscience tells me I am right, and I believe I shall some day reap my reward.” (29)

Stone always planned on returning to the United States and rejoining the Confederate military. In a letter to a friend on Christmas Eve 1863, having only been in Canada for a short time, Stone asked the recipient to “tell Mother her injunction for me to stay here during the war can hardly be obeyed consistently with honor and duty; but for her to rest easy about me till spring.” (30) By April 1864, Stone had begun planning his return, reflecting, “I think it will be by the first of May before I’ll get off.” (31) He ended up returning to the South sometime between mid-spring and early summer 1864, and rejoined General John Hunt Morgan’s regiment. He served under Morgan until the general’s death in September 1864. Stone continued to serve in the Confederate Army until the end of the war, surrendering to the Eighteenth Indiana Infantry Regiment and receiving his parole in May 1865. (32)

After the war, Stone did not regret his support of or allegiance to the Confederate States of America. Put simply in a letter to his mother on June 2, 1865, he stated, “All I regret being in the Army for is the neglecting of my profession.” (33) Later the same month, having returned to Kentucky, Stone expressed that “‘We rebels’ will be as popular as any class in KY ere long; we are apparently so now.” (34) While this popularity might have existed in Kentucky and other Confederate states, the United States government did not view Confederate supporters highly.

“Uncle Henry” Assists His Namesake

On April 8, 1919, Henry Lane Stone gave a speech before Confederate veterans reflecting on his experiences during the Civil War. In the speech, Stone gives an autobiographical account of his memories of the war, primarily from 1862 to the late 1860s. One of the last sections, titled “Special Pardon,” details how Stone offered his allegiance back to the United States:

After the surrender in April, 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation, whereby the rights of citizenship were withheld from certain classes who participated in waging war against the United States Government, among whom were those who had left a loyal State and joined the Confederate Army. It became necessary, therefore, for me to obtain a special pardon from the President, which I did in the summer of 1865, through the aid of my uncle, Henry S. Lane, then United States Senator from Indiana. (35)

Stone’s account, while essentially capturing the nature of the events that occurred, omits some key details. While Henry Smith Lane did help his nephew receive a presidential pardon, Stone’s brother Valentine initiated the process, and Stone was not completely appreciative of Valentine’s inclusion of “Uncle Henry,” as Henry Smith Lane is referred to in letters, in the process.

Valentine first sent a letter to Stone on September 10, 1865, requesting, “If you will write out an application for pardon to the president, stating under which claim you are liable and the circumstances of your case and send it to me immediately . . . I can get it put through for you.” (36) Valentine was a major in the Union Army during the Civil War, beginning his service under General Lew Wallace in the Eleventh Indiana Infantry Volunteers. He remained a high-ranking officer in the United States Army after the war. (37) Valentine believed his status might allow him the opportunity to assist his brother.

However, Valentine was unable to obtain a presidential pardon for his brother. On November 11, 1865, Valentine provided Stone with an update:

I have just received a letter from Uncle Henry [Smith Lane] in reference to your pardon. You see I went to see Attorney General [James] Speed and he told me that if I would get a line from Senator Lane requesting it, he would see that the pardon should be granted, so I wrote to Uncle Henry. He says in reply that if you will send to me so that I could send it to him, the Oath of Allegiance taken by yourself. If you will forward this to me I will forward it to him at Washington and he says he will then see Hon. [Andrew] Johnson himself and get for you. (38)

In addition to Lane’s offer of assistance, Valentine told his brother that Uncle Henry “says that he does not think that it will ever be pleasant for you again to live in Indiana. He says: ‘Henry has cast his lot with the South and it will be better for him to remain there.’” (39) Stone himself had expressed similar sentiments to his parents the previous summer: “I fear arrest for treason against the State of Indiana; and the execution of Andy John’s list of exceptions from amnesty.” (40) With tensions high after the war, Stone probably assumed that an ex-Confederate soldier living in a Union community would cause problems.

Stone apparently was not happy that his brother involved Lane in the pardon process. Valentine wrote Stone on November 28, 1865, to tell him he had received Stone’s Oath of Allegiance. In that letter, Valentine expressed his frustration toward his brother’s lack of appreciation:

I assure you none but the kindest motives actuated me, and if I could have effected it by my own individual exertions I should most certainly have done so without asking my Uncle’s assistance. But when I found I could not obtain it without his assistance I asked for it. . . . There was not an unkind word in Uncle Henry’s letter. He seemed (as he has expressed to me before) deeply hurt that you went south, but now that you have done so he seems to think it best (as I do) for you to remain south. (41)

With or without ill feelings, “Uncle Henry” obtained an official pardon for his nephew at the dawning of the year 1866. Lane wrote to Valentine explaining additional steps Stone needed to take to complete the pardon process: “I herewith send you Henry’s pardon. write to him to fill one of the enclosed blanks & send it to Hon. Wm. H. Se[ward], Secretary of State. He had better go to some officer & take the Amnesty Oath, have it endorsed on the pardon.” (42)

On January 8, 1866, Valentine Stone forwarded the good news to his brother, stating “Enclosed please find Pardon for yourself.” Valentine also included the earlier letter from “Uncle Henry” so Stone could see what his uncle had said, perhaps to correct any previous misunderstandings or misconceptions. (43)

Henry Lane Stone’s letters do not answer all questions, though: Did Stone and Henry Smith Lane have a close relationship? Did “Uncle Henry” and his namesake ever have a debate or conversation about slavery or states’ rights that affected their relationship? It would be interesting to know. But even without such answers, Stone’s letters are a dramatic example of a family divided during the Civil War. For the Stone and Lane families, the letters add context and dialogue to two men’s experiences on opposite sides of the conflict.

Notes

1. Betty Alberty, Sister Rachel West, Robert W. Smith, Collection Guide, Lane–Elston Family Papers, 1775–1936, M 0180, Indiana Historical Society; A Biographical Directory of the Indiana General Assembly: Volume 1, 1816–1899 (Indianapolis: Select Committee on the Centennial History of the Indiana General Assembly and Indiana Historical Bureau, 1980), 228; Theodore Gregory Gronert, Senator Henry S. Lane (Crawfordsville, IN: Montgomery County Historical Society, 1900); Stephen J. Thompson, History of Montgomery County, Indiana, with Personal Sketches of Representative Citizens, vol. 1 (Indianapolis: A. W. Bowen, 1978), 367–68; James A. Woodburn, “Henry Smith Lane,” Indiana Magazine of History 27, no. 4 (1931): 279–87; Olin Dee Morrison, Indiana at Civil War Time: A Contribution to Centennial Publications (Athens, OH: E. M. Morrison, 1961), 11. For overviews of the Whig and Republican Parties, see “Whig Party” and “Republican Party,” in Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com. For additional genealogical information on Henry Smith Lane, see Evan N. Miller and Natalie Burriss, “Lane–Elston Family Genealogical Materials from Montgomery County, Indiana,” in Online Connections, Indiana Historical Society, https://indianahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/Miller_Lane-Elston-Family_OC.pdf.

2. Walter Rice Sharp, “Henry S. Lane and the Formation of the Republican Party in Indiana,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 7, no. 2 (1920): 111–12; Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 1850–1880 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau and Indiana Historical Society, 1965), 72, 98–99, 113; Woodburn, “Henry Smith Lane,” 283–84. In his article, Woodburn shows that Henry Smith Lane was not an abolitionist. Regarding Lane’s view of slavery in the Southern states, Woodburn quotes him: “Wherever slavery exists by local law . . . there it is sacred and is protected by the constitution of the United States.” Woodburn also notes that Lane “believed that any general scheme of emancipation should be accompanied by a plan for African colonization.”

3. Henry Lane Stone, from the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography [pamphlet] (New York: James T. White & Co., 1925), 5–6; Henry Lane Stone, “Morgan’s Men”: A Narrative of Personal Experiences by Henry Lane Stone Delivered before George B. Eastin Camp, No. 803 United Confederate Veterans at the Free Public Library (Louisville, KY: Westerfield–Bonte, April 8, 1919), 4–5; E. Polk Johnson, A History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, vol. 2 (Chicago: Lewis Publishing, 1912), 647–49; Samuel Stone, Kentucky, County Marriage Records, 1783–1965, Ancestry.com. Stone’s mother’s first name is referred to in several documents as Sarah, Salley, or Sally. For example, the 1850 U.S. census uses the name “Sarah,” while the 1870 U.S. census gives “Sally.” In this article I use the name “Sally” due to its use in the biography Henry Lane Stone as well as in Sally Stone’s death record. This record also states that Sally died in Jefferson County, Kentucky, and was buried in Greencastle, Putnam County, Indiana. See Death Record, Sally Stone, Jefferson County, Kentucky, 1852– 1965, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky, Ancestry.com.

4. Johnson, History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, 2:647–48; Biographical Directory of the Indiana General Assembly, 1: 228. Johnson’s work specifically states that Henry Lane Stone was the namesake of Henry Smith Lane.

5. Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 4; 1850 U.S. Census for Samuel Stone, Bath County, Kentucky, NARA microfilm roll M432_191, page 109 A, Ancestry.com; 1860 U.S. Census for Samuel Stone, Franklin Township, Putnam County, Indiana, NARA microfilm roll M653_291, page 110, Ancestry.com.

6. 1850 U.S. Census for Henry S. Lane, Union Township, Montgomery County, Indiana, M432_161, page 435B, image 438, Ancestry.com; Johnson, History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, 2:648; Jesse William Weik, Weik’s History of Putnam County, Indiana (Indianapolis: B. F. Bowen, 1810), 393. It is interesting to note that the 1870 U.S. census records Samuel and Sally Lane Stone living in Bath County, Kentucky. This means that Henry Lane Stone’s parents returned to Kentucky after the Civil War, moving from Union-supporting Indiana to the border state of Kentucky. This move would have brought them in closer proximity to their pro-Confederate family. A reason for their return to Kentucky could have been to live closer to their son Henry Lane Stone, who did not feel safe returning to Indiana, according to family letters. Biographical accounts do record Samuel Stone dying and being buried in Indiana; however, I was unable to find his gravesite. See 1870 U.S. Census for Samuel Stone, Sharpsburg, Bath County, Kentucky, NARA microfilm roll M593_446, page 81 A, Ancestry.com.

7. Johnson, History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, 2:648.

8. Ibid., 2:649; Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 5. Along with several immediate family members, Henry Lane Stone’s uncle Henry Smith Lane also supported the Union. However, Lane’s influence on his nephew and the relationship between Lane and Stone is not known. Moreover, Stone’s relationship with his immediate family members would presumably have been more influential.

9. Johnson, History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, 2:648–49; “Even Cataloging a Bandana Leads to Exciting Discoveries,” Kentucky Historical Society Chronicle (2012): 6–7; Henry Lane Stone, 4–5.

10. 1840 U.S. Census for Samuel Stone, Bath County, Kentucky, NARA microfilm roll M0704, page 195, Ancestry.com; 1850 U.S. Census Slave Schedule, Samuel Stone, Bath County, Kentucky, NARA microfilm roll M432, Ancestry.com. The Stone family owned the same number of slaves (five) around a decade prior to Henry Lane Stone’s birth. See 1830 U.S. Census for Samuel Stone, Bath County, Kentucky, NARA microfilm roll M19_33, page 222, Ancestry.com. After the Stone family’s move to Indiana, it is unknown what happened to the slaves the family had owned.

11. Lane–Elston Family Papers, 1775–1936, box 3, folder 13, Indiana Historical Society. All letters cited in this article come from this collection. The collection includes transcripts of Henry Lane Stone’s Civil War letters; the originals are in the possession of the Kentucky Historical Society (Stone Family Papers, MSS 16). None of the letters are addressed to or from Henry Smith Lane, one of the collection’s primary focuses, but he is mentioned in some of them. It is the author’s assumption that the transcriptions were completed as part of genealogical research, noting the collection contains genealogical materials regarding both the Lane and Elston families. For this article, only the transcripts of the letters in the Indiana Historical Society collection were reviewed. In addition, the Lane–Elston Family Papers includes a transcript of Henry Lane Stone’s Civil War diary (box 2, folder 16). Stone’s entries are brief and only from the latter half of the war, not including his early years fighting for the Confederacy.

12. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel and Sally Stone, December 6, 1862, Lane–Elston Family Papers; Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 5.

13. Ibid.; Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, September 22, 1862, Lane–Elston Family Papers. While Stone writes that he was a part of the “Second Kentucky Battalion,” other published sources, including Stone’s own autobiographical account, state that Stone was in the Ninth Kentucky Regiment/Cavalry. See Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 6; Johnson, History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, 2:649.

14. Morrison, Indiana at Civil War Time, 119; William E. Wilson, “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy, or King of Horse Thieves,” Indiana Magazine of History 54, no. 2 (1958): 127.

15. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel and Sally Lane Stone, December 6, 1862, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

16. Margrette Boyer, “Morgan’s Raid in Indiana,” Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History 8, no. 4 (December 1912), 153–54; Hubert H. Hawkins, “Invasion of Indiana: Morgan’s Raid Brought Five Days of Terror and Hoosiers’ Only Contact with War,” in Indiana and the Civil War (Indianapolis: Indiana Civil War Centennial Commission, 1961), 19; Basil W. Duke, A History of Morgan’s Calvary (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1960), 431–37. For more information on John Hunt Morgan and Morgan’s Raid through Indiana and Ohio, see Morrison, Indiana at Civil War Time, 117–19; Flora E. Simmons, A Complete Account of the John Morgan Raid through Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, in July 1863 ([Louisville, KY?]: Flora E. Simmons, 1863); Wilson, “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy,” 119–30; Edison H. Thomas, John Hunt Morgan and His Raiders (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1975); Arville L. Funk, The Morgan Raid in Indiana and Ohio (1863) (Corydon, IN: ALFCO Publications, 1978); Scott Roller, “Business as Usual: Indiana’s Response to the Confederate Invasions of the Summer of 1863,” Indiana Magazine of History 88, no. 1 (March 1992), 1–25; David L. Taylor, “With Bowie Knives and Pistols”: Morgan’s Raid in Indiana (Lexington, IN: TaylorMade WRITE, 1993); David L. Mowery, Morgan’s Great Raid: The Remarkable Expedition from Kentucky to Ohio (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2013).

17. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, July 8, 1863, Lane–Elston Family Papers; For more detail on Stone’s experience during Morgan’s raid in Indiana and Ohio, see Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 10–13.

18. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, July 21, 1863, Lane–Elston Family Papers; Taylor, “With Bowie Knives and Pistols,” 105–8; Thomas, John Hunt Morgan and His Raiders, 85.

19. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, July 21, 1863, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

20. Ibid.; Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 13; Simmons, Complete Account of the John Morgan Raid through Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, in July 1863, 83–85. Simmons’ account includes a transcription of the Indianapolis Journal article.

21. Henry Lane Stone to Jim Stone, August 19, 1863, Lane–Elston Family Papers; Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 13–17.

22. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, February 5, 1864, Lane– Elston Family Papers; Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 13–15.

23. Henry Lane Stone to French Stone, December 20, 1863, Lane– Elston Family Papers.

24. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel and Sally Stone, December 5, 1863, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

25. Henry Lane Stone to French Stone, December 20, 1863, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

26. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, March 13, 1864, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

27. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, April 3, 1864, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

28. Henry Lane Stone to Jim Stone, undated, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

29. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, February 5, 1864, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

30. Henry Lane Stone to Azariah Gordon, December 24, 1863, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

31. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel Stone, April 3, 1864, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

32. Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 20–22; Johnson, History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, 2:649.

33. Henry Lane Stone to Sally Stone, June 2, 1865, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

34. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel and Sally Stone, June 20, [1865?], Lane–Elston Family Papers.

35. Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 34–35.

36. Valentine Stone to Henry Lane Stone, September 10, 1865, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

37. Stone, “Morgan’s Men,” 32–33; “Stone, Valentine Hughes (1839–1867),” Historical Society of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, https://hsmcpa.org/index.php/visit/visit-historic-montgomery-cemetery/vitae/140-stone-valentine-hughes-1839-1867, accessed April 2019.

38. Valentine Stone to Henry Lane Stone, November 11, 1865, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

39. Ibid.

40. Henry Lane Stone to Samuel and Sally Stone, June 20, [1865?], Lane–Elston Family Papers.

41. Valentine Stone to Henry Lane Stone, November 28, 1865, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

42. Henry Smith Lane to Valentine Stone, January 5, 1866, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

43. Valentine Stone to Henry Lane Stone, January 8, 1866, Lane–Elston Family Papers.

Evan N. Miller is a library associate in the Special Collections, Rare Books, and University Archives at Butler University Library in Indianapolis, Indiana. He is currently completing a dual master’s degree in public history and library and information science at Indiana University–Purdue University, Indianapolis. Evan grew up in Montgomery County, Indiana, and enjoys local history. He is a former intern of the Indiana Historical Society Press.