Purchase Tickets

Farm Life in 1869: The Journal of William Henry Harrison Medsker of Hendricks County

From The Hoosier Genealogist: Connections, Spring/Summer 2019. To receive Connections twice a year, join IHS and enjoy this and other member benefits. Back issues of Connections are available through the Basile History Market.

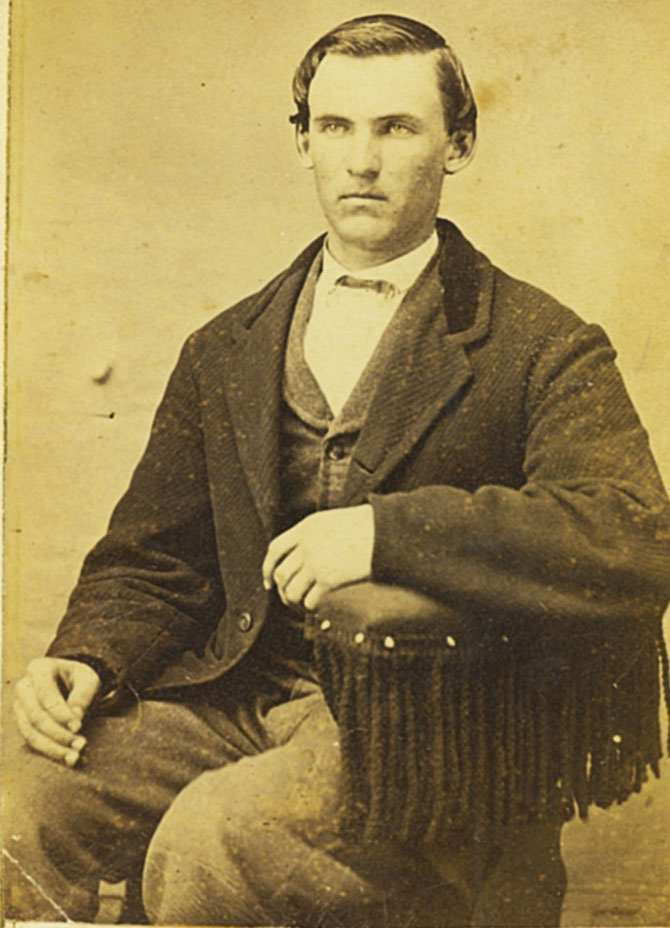

My story begins when I took possession of my great-grandfather’s journal. William Henry Harrison Medsker was nineteen years old when he began recording in a journal his daily activities for the year 1869. My grandmother, Hazel (Medsker) Johnson, who was the youngest of William’s eight children, owned the journal. Grandma had only one child, my father, Marion Johnson, and my brothers and sisters allowed me to take the small, leather-bound book to transcribe and research. In awe of this treasure from almost 150 years ago, I used a magnifying glass to decipher some of the words that are more difficult to read, typed up the entries, and researched the history of the time period.

To determine how my great-grandfather happened to be in Hendricks County, Indiana, near Brownsburg, I consulted Grandma’s large butcher-sheet family tree, family bibles, and books on the history of the area. I traveled to the Hendricks County Historical Society in Plainfield, the Hendricks County Public Library’s Indiana Room, and then to the Brownsburg Public Library. Additional research took me to the Indiana Historical Society and also to my own local Valparaiso (Indiana) Public Library Genealogy Department. Everyone was extremely helpful.

I was able to determine that William’s father, Peter Metsker, was born in Ohio around 1814, though sources vary on the year. Since Peter was a middle child with little chance of inheriting the family land, at about sixteen years of age he struck out in search of his own land and fortune. (1) In The Village of Brownsburg, authors Peg Kennedy and Frankie Konovsek place Peter Metsker in Hendricks County, voting in an election in 1830, but I could find no confirmation of that in other sources. If born in 1814, Peter would have been only about sixteen years old in 1830. Would that have qualified him to vote? (2) It is also possible he was born at an earlier date, making him old enough to vote that year.

I could not understand how Peter could travel through the wilderness at such a young age unless he was with someone else. Family members made the most sense. I was thrilled to find on Rootsweb.com that Peter’s sister Mary (also called Polly) married John Templin in Ohio, and while their first four children were born in Ohio, their next seven children were born in Hendricks County, Indiana. Peter may have traveled west with them. Peter’s older brother John settled in Indiana later, purchasing land in Hendricks County in 1838. (3)

The spelling of John’s name was recorded as “Medsker” instead of “Metsker,” and most documents after 1838 use the “Medsker” spelling. In 1842 after establishing himself as a landowner and farmer, Peter married Elizabeth Brinkley Gray. Four of their children lived to adulthood: John, William Henry Harrison, Mary, and James. (4)

William, often written as WHH, grew up along White Lick Creek near Brownsburg, Indiana. He attended Barlow School, southwest of Brownsburg. From January 4 through March 12, 1869, William mentions attending school almost every day since it was slack time on the farm. I was surprised that he attended school at age nineteen, but I learned that school sessions were short and varied due to seasonal farming activities, and schools accepted young people to age twenty-one at the time. William often returned to the schoolhouse in the evenings to attend spellings, writings, and singings, sometimes several times a week. Evidently these activities were his social life, as he had a good time there and mentions his friends in attendance. Some of the activities were held at other schools, such as Blair, Brown, and Coffin Schools. At this time, small schools were built every two to four miles in Indiana because of the lack of good roads. (5) By early March, William tired of school, writing “Went to school. School seems very dry today. Don’t have any fun any more.” Perhaps the social aspect had worn off or the teacher had become more focused on lessons as the end of school neared.

Much of the journal refers to the weather and to William’s work regimen. In January he shucks corn and chops wood. Splitting rails was an important skill for the pioneer farmer. Not only did the pioneers chop wood to heat their homes and cookstoves, but also to build their homes, barns, fences, corncribs, chicken houses, and other outbuildings. Additionally, William mentions chopping wood for the church, school, and relatives who could not cut wood for themselves.

William and his brother John frequently traveled to “the other place” to feed the livestock and haul manure. They had cows, pigs, sheep, and horses, but I could not tell which property he refers to as “the other place” because Peter owned four parcels of land: 80 acres in section 12, township 16 North, range 1 East; 157 acres in section 22; and two 80-acre parcels along White Lick Creek in sections 27 and 28. (6) Friends’ names listed in his journal would indicate that he most likely lived either in section 22, 27, or 28, not in section 12. In addition, Barlow School was within the vicinity of sections 22, 27, and 28. In addition, sometimes he mentions breaking his horse to ride or to pull a buggy when he goes to “the other place.”

March 23 to April 5 finds William tapping “sugar trees” and boiling the sugar water down into maple syrup. He writes, “Went to writing tonight. James Goudy went home with me after writing. Stopped at Jollies as we went home. We had a good time drinking sugar water.” When the weather cooperates, starting April 8, he prepares to plow. Rain and snow slow his progress, though, forcing him to haul rails, manure, and hay, as well as to reset fence. Twice he mentions “grubbing,” the backbreaking work of clearing trees and rocks from the land.

Because William was a farmer, I used many different sources to understand his references and terminology. First, I usually asked my husband since he is a farmer, and I asked cousins for help also. Of course, the Internet was a great help at defining terms and finding reference books. Two especially helpful books were The Young Farmer’s Manual: Manipulation of the Farm in a Plain and Intelligible Manner from 1860 and a modern work, Childhood on the Farm: Work, Play, and Coming of Age in the Midwest. (7)

Planting crops was quite involved. First, William plows and harrows the ground. Then he plants the grain—oats, wheat, and corn—by hand. The Young Farmer’s Manual relates how grain was planted by hand, an art that few mastered. The sower would carry a bag over his shoulder, take a handful of seed, and throw the grain as the opposite foot rises. The grain should “slip off the ends of the fingers, and not between the thumb and fingers.” For ease of refilling, bags of seed were placed at the end of the row or in the middle of the row if the field was long. The book even includes specific instruction on determining the right size of each handful, the height of the hand, dropping the seed, and sowing on a windy day. (8)

After the corn emerged through the ground, William works to “cross out” the corn. “Crossing out” probably refers to the process of marking the corn rows. Since pioneer farmers did not have weed-killing chemicals like we do today, they planted corn in a checkered manner, plowing both down the rows and between the stalks of corn. (9)

Besides the grain for the animals, William also plants potatoes and watermelons. Twice he mentions finding and picking strawberries and blackberries. In late May after the fields are planted, William helps his mother with the spring cleaning, perhaps moving furniture, beating rugs, and washing heavy quilts. (10)

All was not work for William, however. He was an incredibly social person. In the first thirty pages of his journal, he mentions visiting with seventy-nine people—either he visits them, they accompany him to a meeting or party, or they come to visit him. He enjoys hunting, fishing, and swimming with his friends. Occasionally they spend the night at each other’s houses.

Most Sundays William attends church or goes to “meeting,” perhaps Sunday School, bible study, or a prayer meeting. I could not determine which church he attended most often, but he mentions Abner’s Creek, a Baptist church, and a church in the Burg. Some Sunday evenings he goes to Coffin schoolhouse to “meeting.” Once he attends a Quaker meeting, and the next Sunday he attends the Catholic church in the Burg. Whether he was searching for his spirituality, attending with friends, or just curious, something leads him to various Christian denominations. As an adult, he raised his children in the White Lick Presbyterian Church, and my grandmother attended there until her death in 1978. Since White Lick church was built in 1851 and it was near the Medsker land, that may very well be the church William mentions most often. The church remains today, restored to its original form. A member took me on a tour of it, but unfortunately all the church’s records were lost in a fire. This picturesque little church is sometimes referred to as the Church in the Wildwood. (11)

On Sunday, May 16, William has an adventure. He and his friends evidently “borrow” a handcar from the railroad and use it to pump their way to Clermont, Indiana. “I and F. Lingerman, Jim John Black, E. Togan, and two Irish took a ride on the hand car. We went to Clermont. Got throwed off the track twice but nobody hurt. We went about ten miles in minutes.” The meaning of being thrown off the track is not clear, but it could have led to catastrophe, based upon a headline from the New York Times of August 25, 1899: “Boys Killed and Maimed: Stealing Ride on

Handcar which Ran Away Down Grade—One Dead, Twentytwo Hurt.” At least William reports that no one was hurt in his escapade.

Late June and early July find William plowing the fields and cutting clover. Henry Teak helps harvest the wheat, and then William returns the favor. They cut the wheat and bundle it into shocks, like corn. Later they stack the wheat until needed for threshing or feeding livestock. A month later William is threshing those stalks and helping neighbors thresh for several days. An enjoyable time for the whole community, threshing brought neighboring farm families together. Men would carry the sheaves of wheat, run the thresher, and bag the wheat; women would cook a huge harvest dinner, and the children would play games and run errands. (12)

On Saturday, August 7, 1869, William relates, “Went to the school meeting after noon. Went from there to the Burg awhile. An excitement about the eclipse of the sun. The eclipse was almost total. It got tolerably dark. I saw two stars.”

Thursday, September 30, he writes, “I, John, S. Bursott, and Mary went to the fair today. Started at 6 am, got there at 8. I had a good time. We started home at dark and got home at 11.” I assume that William, his brother John, sister Mary, and a friend took the train from Brownsburg to the Indiana State Fair. Luckily, they did not attend a day later because on that day the state fair was the scene of a steam boiler explosion that killed almost thirty people. (13)

October finds William cutting up corn and “stripping cain.” Sugar cane, or sorghum cane, was raised to provide sorghum for sweetening in the kitchen and to add to the livestock feed. The plant looks similar to corn except for a seed head at the top. At harvest time each stalk was cut by hand and the seed head removed for next year’s planting. The leaves were stripped off, and the cane stalk fed through a squeezing machine to extract the juice, which was boiled down into thick syrup. The stalks were fed to animals as well. (14)

Through October and part of November, William gathers apples in addition to his daily chores. Some he sells in town, and others he uses for cider. One night he, “John, Mary, and Martha Hylton went down to Jim Sheetses to an apple peeling.” He reports that he “had a tolerable good time.” They may have cooked the apples with cider and molasses to make apple butter and then divided the apple butter to take home. One day in October, William works on the road. According to Kennedy and Konovsek, “farmers generally were assigned the task” in Hendricks County of maintaining the roads throughout the year. (15)

On October 27 William writes of a puzzling event, “I went over to the church to night. We organized a society.” He called it the Star Society, and they met weekly. Eventually he relates, “Decided tonight that we would have an Exhibition the 21 of this month [December]. We elected performers most of them tonight.” I was perplexed by this society. Was the purpose just a gathering of friends? What kind of “exhibition” did they hold? Online research presented several possibilities but nothing conclusive. Childhood on the Farm shed some light on the matter, stating that young adults in farming communities would form social organizations for entertainment and enlightenment. (16)

I contacted the Robert T. Ramsay Jr. Archival Center at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, and posed my question of what the society could have been. The consultant there revealed that literary societies were popular on campus and across the country at that time. They were a common form of socializing in the mid-nineteenth century and a precursor to the college fraternity system. Literary societies held speeches, debates, and readings, and showcased some of them at exhibitions. This is most likely the purpose of William’s Star Society. (17)

Unfortunately, the society’s exhibition was not well attended because of bad weather, but William enjoyed it nonetheless. Then on December 22 he had another treat: He and his sister and her friend traveled to Crawfordsville for an exhibition. For two days he stayed with a friend and then returned to Brownsburg to see another exhibition.

Also in December William mentions, “Killed hogs today.” According to Feeding Our Families: Memories of Hoosier Homemakers, butchering day was a big day for farmers and their families. Butchering was hard work—dirty, smelly, greasy. Neighbors would often gather and butcher several hogs at a time. The process involved killing/shooting the hog, scalding the hog in hot water, scraping the bristles, hanging and gutting the carcass, and cleaning the entrails for sausage. Cleaning the entrails was the women’s worst job because of the mess and the smell. If the hog had worms, holes in the casing would have to be trimmed. The hog’s bladder was cleaned and blown up as a balloon for the children. Fat from the hog was rendered into lard through heating and then pressing. After the lard was pressed out, cracklings (the rind) were left to eat. Children would sometimes then throw corn kernels into the tablespoon or so of lard left in the bottom of the kettle and feast on the delicious popcorn produced. (18)

I was disappointed that William recorded nothing special for Christmas Day because I wanted to know how the family celebrated Christmas. He simply writes, “I am at home this morning. Nice day. Hauled hay before noon. I went over to Dan Flins after noon. Stayed until evening. Went down to Will Hyltons a few minutes. Went home. Stayed there tonight. Had a very good time after noon.”

On January 5, 1870, William’s brother John marries Hester Patterson, and they enjoy “a splendid supper.” After the wedding William goes to the Star Society and is elected treasurer. In several pages at the back of the journal William records the monthly cash account for the society through December 1870. He also records what he pays for personal items and how much he pays friends for their work. His records also show how much he pays his father for various animals and how much money he borrows from his father at 10 percent interest. Perhaps by this time he is establishing his own farm.

William married Melinda/Malinda Jane Merritt on December 20, 1871. She was eighteen; he was twenty. Together they had eight children: Nora, Cora, Ora, Mary, Lillian “Lillie,” Charles, Pearl, and Hazel (my grandmother). The property where they raised their family is now owned by another couple, who have attempted to keep the home as true to the original structure as possible. (19) When the current owners refurbished the fireplace, they discovered the original brick fireplace used by the Medskers. They graciously showed my grandmother the home before her death and showed me more recently. They also provided an 1890s picture of the home and took me on a tour of the surrounding area.

William Henry Harrison Medsker’s 1869 journal provides a glimpse into one young man’s life in the countryside of mid-nineteenth-century Indiana. Education and the Star Society were important to him, as can be seen from his numerous mentions of both in his journal. William lived a long life, farming until he was sixty, and dying on January 27, 1930, at age eighty. One obituary states, “Uncle Billy, as he was familiarly known was a good citizen, of a cheerful disposition, known for his generous spirit, no one in need ever appealing to him in vain.” It goes on to report that, at the time of his death, William had eighteen grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. He was buried in Greenlawn Cemetery in Brownsburg. (20)

Notes

1. 1870 U.S. Census for Peter Medsker, Lincoln Township, Hendricks County, Indiana, NARA microfilm roll M593_322, page 446B, available at Ancestry.com; “Mary M. ‘Polly’ Medsker Templin,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/23624783/mary-m_-templin, accessed May 2019; “Peter Medsker,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/58899975, accessed February 2019. According to these sources, Mary and Peter were siblings. As well, an obituary for Mary from the Hendricks County Republican, September 5, 1895, lists Mary’s birthplace as Highland County, Ohio, making it possible that Peter was born in the same place. The majority of the documentation on Peter’s birthplace includes only the state, not the county. This source also lists Peter as having six siblings. He was not the exact middle child, but he was neither the oldest nor the youngest.

2. Peg Kennedy and Frankie Konovsek, The Village of Brownsburg (Robinson, IL: Lamplight Publishing, 1998), 18. Voting in the early nineteenth century was limited to white men and landowners and sometimes had preliminary tests, though some states had different laws. For a general timeline of voting in the United States, see “History of Voting,” Scholastic: Teachers, https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/history-voting/, accessed February 2019.

3. R. Hunziker, “Various Families from Hendricks and Morgan County, Indiana: Mary Medsker,” RootsWeb, https://wc.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=rmhunziker&id=I10095, accessed February 2019; Gregory Boyd, Family Maps of Hendricks County, Indiana, with Homesteads, Roads, Waterways, Towns, Cemeteries, Railroads, and More (Norman, OK: Arphax Publishing, 2006), 119. Peter is also shown as owning land at this time. His last name is spelled Metsker.

4. R. Hunziker, “Various Families from Hendricks and Morgan County, Indiana: Peter Medsker,” RootsWeb, https://wc.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=rmhunziker&id=I9754, accessed February 2019. Noting Peter had lived in Hendricks County since circa 1830, it is probable that in the time between his arrival and his marriage a decade later he had bought land. The 1840 U.S. census did not record land ownership. However, the 1850 U.S. Census lists Peter as a farmer owning real estate with a value of $1,360. See 1840 U.S. Census for Peter Medsker, Hendricks County, Indiana, NARA microfilm roll M704, page 39, Ancestry.com; and 1850 U.S. Census for Peter Medsker, Brown Township, Hendricks County, Indiana, NARA microfilm roll M432_150, page 157A, Ancestry.com. See also 1880 U.S. Census for James Medsker, Hendricks County, Indiana, NARA microfilm roll 283, page 662C, Ancestry.com; Boyd, Family Maps of Hendricks County, Indiana, 114. The latter source lists Peter Metsker as having bought land in 1838.

5. Kennedy and Konovsek, Village of Brownsburg, 32, 41; Pamela Riney–Kehrberg, Childhood on the Farm: Work, Play, and Coming of Age in the Midwest (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2005), 62, 64.

6. Atlas of Hendricks County, Indiana, to which Is Added Various General Maps, History, Statistics, Illustrations (Chicago: H. Beers and Co., 1878), 25.

7. S. Todd Edwards, The Young Farmer’s Manual: Manipulation of the Farm in a Plain and Intelligible Manner (New York: C. M. Saxton, Barker, and Co., 1860); Riney–Kehrberg, Childhood on the Farm.

8. Edwards, Young Farmer’s Manual, 351–64. Planting seeds without any farm implements or machinery is covered in Chapter 8, “Sowing Grain by Hand.”

9. Timothy A. Nelson, farmer and husband of the author, in discussion with the author, July 2011; Cross-plowing is briefly discussed in Edwards, Young Farmer’s Manual, 322, 334.

10. Riney–Kehrberg, Childhood on the Farm, 44.

11. History of Hendricks County, Indiana, together with Sketches of its Cities, Villages and Towns, Educational, Religious, Civil, Military, and Political History, Portraits of Prominent Persons, and Biographies of Representative Citizens (Chicago: Inter-State Publishing, 1885), 665, which states that “Mr. and Mrs. Metsker are members of the Presbyterian Church.” See also Kennedy and Konovsek, Village of Brownsburg, 100–1.

12. Eleanor Arnold, Feeding Our Families: Memories of Hoosier Homemakers, 1890–1930 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 133–44.

13. “Explosion of a Steam Boiler at the Indiana State Fair,” Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, 1869, Newspaper Graphics Collection, P 0100, Indiana Historical Society.

14. “Who Are We?” Townsend Sorghum Mill website, http://www.townsendsorghummill.com/, accessed February 2019.

15. Kennedy and Konovsek, Village of Brownsburg, 119.

16. Riney–Kehrberg, Childhood on the Farm, 151–52.

17. Robert T. Ramsay Jr., Reference Consultant, Archival Center at Wabash College, in discussion with the author, Fall 2011. For more information on literary societies in the Midwest, see Becky Bradway–Hesse, “Bright Access: Midwestern Literary Societies, with a Particular Look at a University for the ‘Farmer and the Poor,’” Rhetoric Review 17, no. 1 (Autumn, 1998): 50–73.

18. Arnold, Feeding Our Families, 40–46.

19. R. Hunziker, “Various Families from Hendricks and Morgan County, Indiana: William H. H. Medsker,” RootsWeb, https://wc.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=rmhunziker&id=I23680#s1, accessed February 2019; Obituary for Malinda Jane (Merritt) Medsker, Brownsburg Record, May 9, 1924, available on Brownsburg Public Library Obituary Finder, obit.bburglibrary.net/obitsystem, accessed February 2019; The 1880, 1900, and 1910 U.S. censuses, available on Ancestry.com, show William and Malinda Medsker and their family living in Lincoln Township, Hendricks County, Indiana, which is the location of Section 22.

20. Death Certificate for William H. H. Medsker, Indiana Archives and Records Administration, Indianapolis, Death Certificates, Year: 1930, Roll: 01, available on Ancestry.com; “Uncle Billy Medsker Died Here Monday,” unnamed newspaper, article clipping, January 31, 1930, found in family bible of John T. and Hester A. Medsker, courtesy of Janet Owen. For additional obituaries for William H. H. Medsker, see also “Death at Brownsburg,” Danville Republican, January 30, 1930; and “Obituary for H. H. Medsker,” Plainfield Messenger, January 30, 1930.

Nancy J. Nelson, from Hobart, Indiana, taught English at Hebron High School for thirty-one years. After retirement she wrote “A Year in the Life of William Henry Harrison Medsker: His Personal Daily Journal, 1869,” and had a few copies spiral bound. Copies are available at the Indiana State Library, and at the public libraries in Hendricks County, Brownsburg, and Porter County in Indiana. She also wrote and bound a similar piece using her Grandma Hazel’s journal and photos detailing a 1907–1908 trip to California that she took with her family, including William Medsker, titled “Grandma Hazel’s Journal.”