Purchase Tickets

Don’t Touch That Dial: The Early Years of WOWO in Fort Wayne

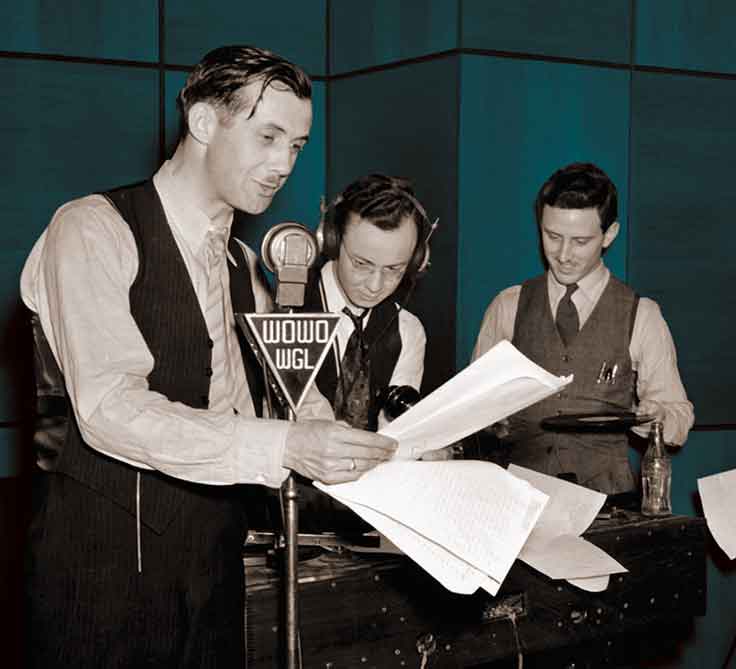

From Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, Winter 2018. To receive Traces four times a year, join IHS and enjoy this and other member benefits. Back issues of Traces are available through the Basile History Market. Photo: first broadcast of basketball game play-by-play, IHS, WOWO Radio Station Photographs Collection, P 524.

Radio station WOWO in Fort Wayne first signed on the air on March 31, 1925, with 500 watts at 1320 kilocycles. The year before, musicians had gathered in the home of Harold Blosser at 2708 South Wayne Avenue for an experimental radio broadcast, which included an opera singer from Bluffton, the Allen County treasurer who did some old-time fiddling, and others. Using a five-watt transmitter, the broadcast had a limited range, but it was a hit. Fred Zieg, owner of the Main Auto Supply store in downtown Fort Wayne, had been looking for a way to promote the sale of Dayfan radios. He was pleased to receive hundreds of calls following this experiment. Kneale D. Ross, a salesman at the store, convinced Zieg that for $150 he could build a radio station above his store at 213 Main Street—WOWO was born. A listener contest came up with the slogan “Wayne Offers Wonderful Opportunities.”

The Indiana Historical Society William Henry Smith Memorial Library holds a WOWO Radio Station Photographs Collection (P 524), consisting of ninety-eight black-and-white photographs that show the station’s facilities and staff members. The majority of photographs are not dated but have been determined to be from the late 1920s through the 1940s. The photographs show musicians, comedic performers, and announcers, as well as programs that were performed in the presence of audiences, including The Hoosier Hop and Modern Home Forum. The first broadcast of a basketball game play-by-play in the studio via Western Union ticker, the Man on the Street program in front of the Patterson-Fletcher Company store, and a quiz show called Do You Know the Answer are also depicted.

In the 1920s there were few rules for radio, and it was a time of great creativity and experimentation. Listeners were so amazed by the sounds that came through their radios that hearing anything at all became entertaining. Radio gave everyone, rural and urban alike, access to a broader world and new ideas. Beyond providing entertainment, radio had the ability to alert people to important news faster than newspapers could. During natural disasters, broadcasters organized relief efforts, provided vital information, and calmed fears. As Hilda Woehrmeyer, an employee of the Main Auto Supply Company and later a WOWO broadcaster, said, “radio makes a neighborhood of a nation.”

General Electric, Westinghouse, Amer-ican Telephone and Telegraph, and the Radio Corporation of America organized the National Broadcasting Company to provide national programming. NBC was the first full-service radio network in the United States. Its first broadcast, at 8:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on November 15, 1926, was a four-and-a-half hour gala of the leading musical and comedy talent of the day originating at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. Performers included Will Rogers, vaudeville comedy duo Joe Weber and Lew Fields, the New York Symphony Orchestra, Vincent Lopez and his

orchestra, and other dance bands. Airing over a network of twenty-five stations as far west as Kansas City, nearly half of the country’s five million homes with radios tuned in to the program.

The first coast-to-coast broadcast followed on New Year’s Day 1927, with coverage of the Rose Bowl football game in California. Beginning that day, NBC ran two networks, identified as NBC-Red and NBC-Blue.

Radio stations provided their own local programs for a few hours a day. Through affiliation with a network they would fill other hours with national programming. Early in 1927, WOWO increased its power to 5,000 watts. On September 18, 1927, WOWO became a pioneer station of the CBS network along with fifteen other stations. In 1928 Zieg bought another station that became WGL (What God Loves) and operated it from the WOWO facilities.

In 1928 the new Federal Radio Commission ordered most stations in the country to change their broadcast frequencies at 2:00 a.m. Central Time on November 11. The purpose was to reduce interference and generally add some order to the growing radio industry. WOWO moved to 1160 kilocycles. The following April, WOWO’s power was increased to 10,000 watts. At this time, the station shared its frequency with WWVA, a radio station in Wheeling, West Virginia. The two stations adhered to a schedule, with one station signing off before the other began its broadcast.

In the 1930s WOWO was the first station to broadcast a basketball game and the first to air a Man on the Street program, which it did from the lobby of the Old Indiana Theater. The Hoosier Hop was a weekly half-hour show on WOWO beginning in 1932 that aired for more than fifteen years except for an interruption during World War II. The show had a rural flavor and offered such fare as traditional American folk music, square-dance music, and yodeling.

Bob Sievers spent his entire career at WOWO, first signing on the air on December 4, 1932, when he was a freshman at South Side High School. His starting salary was five dollars per week. Through all four years of high school, he signed the station on the air each morning from the Gospel Temple after completing his Fort Wayne Journal Gazette newspaper route. Sievers remembered having to walk up a long stairway to the second floor of the Main Auto Supply Company building to get to the WOWO studios. “I remember the one studio where we did a lot of announcing had old wooden doors that you closed,” he said. “The rats chewed holes under the studio door where they could run in and out.”

Sievers became a full-time announcer at WOWO on August 2, 1936, the same month that Zieg and his associates sold WOWO and WGL to Westinghouse. Sievers’s five decades on the air were interrupted only by his military service during World War II and the Korean War.

Howard D. “Tommy” Longsworth was hired as a staff musician at WOWO in 1936. He recalled performing in the studio above the Main Auto Supply Company: “So, you had these little narrow stairs that you had to go up, and every time you did—according to what kind of an instrument you were carrying—you would generally bang it on the wall, because there wasn’t any light going up there. You finally got up to the end of this, and then you came into a hall. At the end of one hall was what they called Studio A and the other end of the hall was Studio B.” The studio was a room about twenty feet by thirty feet with no acoustical treatment. Longsworth remembered having the window open in the studio on a hot day and the noise from a car below on the street made “all kinds of racket. So this went over the air, too. We would have to go over there real quick and slam the window down so it wouldn’t drown us out. . . . You just thought of it as you went along. It wasn’t planned at all.”

The station’s engineering controls were in a small closet in the studio and the first transmitter was on the building’s roof. A small room encased in glass allowed about five or six visitors to watch performances. Longsworth said he would hang out there waiting to see if he could get on the air if there was extra time or somebody failed to show up. He recalled barking like a dog for a program sponsored by Wayne Dog Food and getting paid more to do that than for playing his bass fiddle.

On May 1, 1937, WOWO joined the NBC-Blue Network, which became ABC in 1943. That same month the station moved into new studios built by Westinghouse at 925 South Harrison Street. More than 10,000 listeners visited the studios in the two-day open house and congratulatory messages were received from around the world, including one from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The station now had more studios, and these had observation rooms that were tiered and could seat about fifty people. The studios themselves could hold 100 to 150 people for shows with live audiences.

Sievers said that audience participation was an important part of WOWO. He recalled:

For each studio that we had when we were on Harrison Street or on Washington Street, or even the original station down on Main Street, for each program that we had, we would have a big observation room for people to sit there and watch the program. . . . For instance, Jane Weston conducted the Modern Home Forum ladies’ program in the morning. Ladies would sit right in the studio and watch her bake. We always had a roving microphone where we would talk to the people in the audience. . . . I had a man on the street program . . . from a number of different locations . . . and everybody would gather around the sidewalk, and I would introduce the show by saying, “One moment, one moment, please.”

Modern Home Forum was a home-maker show that aired on WOWO from 1937 to the early 1960s. It had a live studio audience most of the time and offered household hints and cooking lessons. It was hosted by “Jane Weston,” which was an air name used by several different women at WOWO over the years in homage to Westinghouse, the station’s owner. The name was used on a number of Westinghouse stations for local homemaker programs. WOWO’s first Jane Weston was Dorothy Wright, who was born in West Lafayette, Indiana, the daughter of Reverend Manfred C. Wright.

The popularity of programs was based on how much mail people in the show received. Whether the comments were negative or positive was not taken into account. Jane Weston offered a lot of giveaways to the audience, so she would receive hundreds of thousands of pieces of mail for that. In the daytime the station did local broadcasting and advertisements. The network affiliations provided the big, prime-time evening shows, such as Dragnet, The Shadow, The Ed Sullivan Hour, and Jack Benny.

In 1941 the North American Radio Broadcasting Agreement required most AM stations to change frequencies. This resulted in a massive shifting of radio-station dial positions across the country. A photograph in the collection shows WOWO staff as the station moved from 1160 to 1190 kilocycles at 2:00 a.m. Central Time on Saturday, March 29, 1941. That same year WOWO was authorized to stay on the air continuously full time. It aired national shows such as Fibber McGee and Molly and The Lone Ranger. Some of WOWO’s local shows were also broadcast more widely through networks.

The Hoosier Hop was revived in July 1943 as a studio broadcast with a cast of about fifteen people. By October it moved to the Shrine Auditorium in Fort Wayne, where a cast of more than thirty performed to crowds numbering 4,000. The cast also appeared at fairs, bond rallies, and other civic functions. On May 5, 1944, the Hoosier Hop began to air on the Blue Network to a wider national audience with a full fifty-five-minute show.

The WOWO Photographs Collection includes several photos of Franklin Tooke, who began his broadcasting career at the station in 1935. He became a Westinghouse employee the next year when the company bought the station. Beginning in 1946 he worked as program director and general manager at other Westinghouse stations in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Boston, and Cleveland.

Eldon Campbell was hired as an announcer at WOWO in 1938 and became program director in 1941. He worked at WOWO until 1945, when he moved on to a station in Portland, Oregon. From 1950 to 1956 he was an executive sales representative with Westinghouse Broadcasting in New York City. In 1957 Campbell became vice president and general manager of Indianapolis’s WFBM radio and television (today WRTV), a position he held until 1973. He also taught a radio and television management course at Butler University. In 1974 he became director of the Department of Commerce for the State of Indiana. He was active in Indianapolis civic affairs including the 500 Festival committee, the Boy Scout Council, and Junior Achievement. He was presented the Jefferson Award for outstanding public service in 1987 by the Indianapolis Star.

Hilliard Gates (born Hilliard Gudelsky) was hired as an announcer by WOWO in 1939. He remembered: “WO and WGL—we were together in those days and came out of the same studios, but not the same programming. We were a Blue network NBC station—Red network on WGL. They were both owned by Westinghouse and they were broadcasting simultaneously. We didn’t duplicate very often. We might on a July 4th parade or something like that—put it on both stations. We had sales people for WGL and sales people for WOWO. . . . The announcers did both stations.” Gates said that when he first arrived at the station he asked, “How do you know if you’re on WO or WGL?” The answer he got from the program manager was, “You’ll know.” But apparently it was not always clear. Gates recalled a time when “Sievers had to make a station break, and he was in the booth where you say, ‘This is WOWO Fort Wayne.’ You know, NBC had the chimes, and then you came in and said, ‘This is WOWO Fort Wayne.’ And one noon, it was time for the station break, and Bob said, ‘This is ah, ah, WOWO—no, this is WGL—no, it’s WOWO.’ Finally, he said, ‘What the hell station is this anyway?’”

Gates was a sportscaster, announcing the high school games on WGL and the college games on WOWO. When Gates first arrived in Fort Wayne, the station was broadcasting only basketball. He convinced the station manager that WOWO could cover college football games. And then when the Pistons started to play professional basketball in Fort Wayne in 1941, WOWO aired all of its games until the team moved to Detroit in 1957.

Hoosier broadcasting legend Tom Carnegie (born Carl Kenagy) started as an announcer for WOWO in 1942. He took a train on the Wabash Railroad from Kansas City to Fort Wayne for an interview at WOWO and accepted the job and a salary of thirty-four dollars per week. At Kansas City radio station KITE he had been paid fifteen dollars per week for working a minimum of sixty hours a week while still in college. WOWO program director Campbell had Kenagy change his name when he started at the station.

Carnegie said that in the beginning of his time at WOWO, he arrived at the station at 6:00 a.m., “ripped the news off the wire,” organized the news himself, and then read it on the air at 6:30 a.m. Eventually he was asked to join Jane Weston on the half-hour homemaker show at 1:00 p.m. to ad-lib about recipes. He was paid an extra three dollars a week for participating on that show. In a 1994 interview, he recalled, “I took my first three dollar talent fee and bought a coffee table. I will always remember that, and I still have that coffee table.” He also remembered that the station was “originating programs regularly to both the Red and the Blue NBC networks. Back in that era, the Red Network was the number one network of NBC, and the Blue Network was trying to be established on its own. The Blue Network eventually became ABC, but they were both owned by NBC at that time.

“What a wonderful opportunity for me as a youngster to have lots of ballgames to do, lots of opportunities for ad libbing, lots of opportunities for studio programs, for just simple station breaks. No recorded station breaks—everything was live. . . . Once in a while I would forget which station I was on. I would go into a studio, and that studio would be WOWO at that time, and a half-hour later, it could be a WGL studio,” Carnegie recalled.

NBC picked up some of WOWO’s musical programs, such as The Hoosier Hop, which was performed by local country musicians who worked for the station as well as doing shows on the side. WOWO had a studio orchestra on staff, which was very rare.

Carnegie learned how to broadcast a basketball game by Western Union ticker. The local National Basketball League team at that time was the Fort Wayne Zollner Pistons, owned by Fred Zollner who had a piston-manufacturing company. To save money, Carnegie did not travel to away games. A Western Union operator would sit in at the game in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, for example, and “would send back dot-dash-dash, what was going on.” Sometimes Carnegie would have to call a time-out, even when one was not actually called at the game, just so he could catch up and figure out what was happening. He worked at WOWO for three years. Carnegie was lured to WIRE in Indianapolis, where he became the chief announcer for the Indianapolis 500. He began to teach radio at Butler in 1949, and founded radio station WAJC there. In 1953 he moved to television, as director of sports for WFBM Channel 6, a position he held until 1985.

WOWO increased its power over the years and switched back and forth from AM to FM. There were also changes in ownership and programming format. In the 1950s radio got new competition for audiences from television. People could now see what was happening instead of only hearing about it. The early days of television mirrored the early days of radio in terms of people’s amazement and the lack of sophistication of programming. On February 1, 1954, WOWO’s power increased to 50,000 watts, as powerful as any station in the country. WOWO earned the nickname “The Voice of a Thousand Main Streets” and became one of Indiana’s best-known stations.

The station’s personnel looked back on WOWO with fondness and appreciation. “My entire fifty years at WOWO, our staff, we were really always like one big happy family,” Sievers recalled. “We had our Christmas parties and our summer get-togethers at the lake and had cook¬outs—the engineers, the producers, the sales staff, all the different departments.” WOWO had a booster club, a softball team, and a basketball team. The station played against other company teams, such as General Electric and Magnavox. Gates said that the station’s staff “was a family, and that’s why they were so successful,” and remembered that “the greatest group of people that I worked with in my radio career was the staff that Westinghouse assembled at WOWO in Fort Wayne.”

Barbara Quigley is senior archivist, visual collections, for the Indiana Historical Society William Henry Smith Memorial Library. Her article on the library’s Lassen Family Photographs Collection (P 562) appeared in the summer 2017 issue of Traces. In 1999 the IHS Press published “In the Public Interest”: Oral Histories of Hoosier Broadcasters, compiled and edited by Linda Weintraut and Jane R. Nolan. The book includes interviews with such WOWO personnel as Tommy Longsworth, Bob Sievers, Eldon Campbell, Hilliard Gates, and Tom Carnegie.