Plan your visit

The Legacy of Figueroa Printers, Indiana’s First Spanish Language Newspaper

December 7, 2023

The early Mexican communities of the 1920s in Indiana Harbor (East Chicago) and Gary were socially active and culturally vibrant. Early laborers came to Northwest Indiana and Chicago around 1918, recruited as foreign laborers to work in war-relief-related industries during World War I via Departmental Order No. 52461/202. The 1920s saw an increase in arrivals of families and individuals from Mexico’s middle class, who were political or religious refugees from the Mexican Revolution. Those who did not come directly from Mexico came from the American west, mostly from the railroad and agricultural industries. The decade not only saw the exponential growth of Indiana’s first Mexican Colony but also the establishment of Indiana’s first Spanish language newspaper, Latino publisher, community library, and the early beginnings of a literary group all housed under one roof at Figueroa Printers on Deodar Street in Indiana Harbor.

Exterior Photo of Figueroa Printers, late 1930s. Courtesy of Irene Osorio, Indiana Historical Society.

In 1925, a young bride by the name of Consuelo Carillo Figueroa and her infant son (Francisco Jr.) would join her husband, Francisco, and brother-in-law in Indiana Harbor. Consuelo lived a life in Mexico unlike many other Mexicans in Indiana, her family owned two Estancias or Haciendas (El Salto and La Quemada) during the Mexican Revolution. Because of this, some of her family members were publicly targeted and executed. Her daughter Irene recounts in a 2017 oral history interview that Consuelo’s father would leave dishes filled with coins in open windows of their home to avoid harassment. By the time Consuelo came to the United States, she had little to nothing left of the life she once lived. What she did bring with her from that life was her education, graduating from El Colegio Renacimiento de Mujeres in Guadalajara, Jalisco.

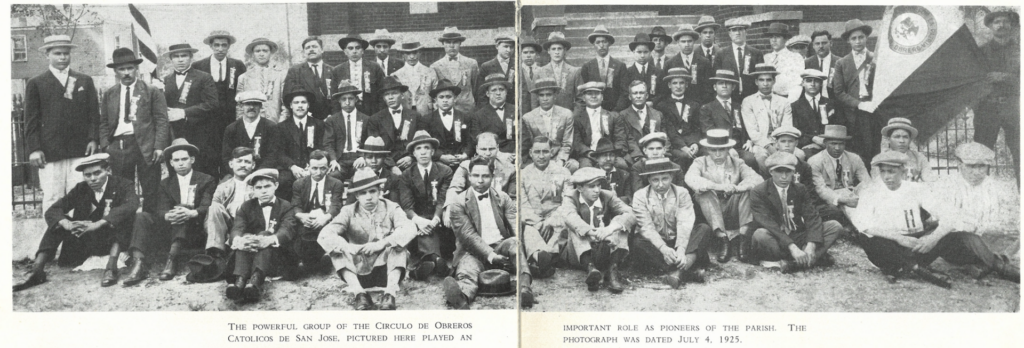

In 1925 her husband Francisco and brother-in-law Benjamin in Indiana Harbor established Figueroa Printers. Francisco and Benjamin, both steelworkers, were a part of the founding and establishment for a local chapter of a mutual aid society called *Circulo de Obreros Catolicos “San Jose” (Catholic workers circle “St. Joseph”) whose slogan was “For God, For Country, and For the Worker.” This chapter originated out of the larger Circulo de Obreros Catolicos group, born out of the late 1800s Catholic Action Movement in Argentina. This is the first chapter of an Obreros group in Indiana, functioning in the same model as the originating group with a mutual aid society and a newspaper to uplift the working class.

The Figueroa printshop on Deodar Street served as one of the many early meeting places for the Obreros and eventually housed a small library for the Mexican colony. Some of the members of this men’s group were editorial staff for Indiana’s first Spanish language newspaper El Amigo del Hogar (A Friend of the Home), a weekly publication that ran from 1925 until the early 1930s.

This newspaper served as outreach for this group, with essays on Catholicism, education, the arts, and Mexican culture. They reported happenings in Mexico, across the United States and in their own community. There were numerous local announcements, some of note were of an upcoming information session about the new St. Catherine’s Hospital (est. 1928), regarding hospital etiquette and protocol, and job opportunities at the growing Inland Steel Company (presently Cleveland-Cliffs, Inc.).

The goals of this group were to start a Roman Catholic church, establish a library, educate the colony, and create wholesome forms of entertainment. This was all achieved by the end of the decade. Notably, they were critical in the early Latino Arts Movement in Indiana. Unfortunately, this was a men’s group, and the work and critical support of women in the colony were not well documented. However, we know that women like Consuelo was as much a part of Figueroa Printers and the publishing of the newspaper as the men, evidenced by her business card for the print shop. Although not publicly listed as a part of the newspaper editorial staff, she was known to review content before the moveable type was set for printing.

Francisco and Consuelo’s business cards for their print shop, Figueroa Printers. Courtesy of Irene Osorio, Indiana Historical Society.

In a recently acquired letter from 1931, the secretary of Circulo de Obreros Catolicos “San Jose” wrote to Consuelo, requesting her to serve on a jury for a “Concurso de Pensamientos,” an essay contest that was part of a festival for the group’s 6th anniversary. Accompanying the letter was the request for essays and its requirements. From personal accounts of other researchers who knew Consuelo when she was living, she was highly regarded.

[Cropped Photo] Silver Anniversary, Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish, East Chicago, Indiana 1927-1952

Group Photo of Circulo de Obreros Catolicos “San Jose” (likely) in front of St. Demetrius Roman Catholic Church at (3901 Butternut Street) on July 4, 1925, Indiana Historical Society

Cropped photo from El Amigo del Hogar, April 17, 1927. Future and Past Presidents of Circulo de Obreros Catolicos “San Jose” (1925-1927), L to R: Eduardo I. Robles, Benjamin Figueroa, and J. Jesus Cortes. Courtesy of Irene Osorio, Indiana Historical Society

Previously mentioned, the Figueroa brothers were part of the founding of the group, Circulo Obreros de Catolico “San Jose,” they are pictured in the two photos above. Francisco is in the top photo, seated in the third row fourth from the right. And in the second photo Benjamin is seated in the center, he is noted as this group’s first president. Benjamin would return to Mexico sometime after the Great Depression or during the Mexican Repatriation movement. Francisco and his family would remain, and he kept on with Figueroa Printers, sustaining the business by doing commercial and personal printing. Francisco would pass away in the early 1950s, but Figueroa Printers remained in business until the late 1980s, ran by Francisco’s two sons. Those two sons went on to start The Latin Times, a bilingual newspaper in 1956, which ran until the late 1970s. It documented the Viva Kennedy movement, community perspectives during the era of urban renewal, and other key moments of Latino History in Indiana. After The Latin Times ceased publication, the printshop would continue to do commercial printing for local government and businesses until the Figueroa brothers retired.

Figueroa Printers served as Indiana’s first Spanish-language newspaper publisher, and the story of the business and the people who ran it solidifies Francisco and Consuelo Figueroa’s place in Indiana history.

(*) The Circulo de Obreros Catolico (Catholic Workers Circle) was a part of the Catholic Action Movement that began in Argentina in the late 1800s, championed by a German Redemptionist leader and exile, Frederico Grote. Frederico or Frederick (Fredrik or Frederik) was a German Catholic leader, stripped of his citizenship and exiled during Kulturkampf in 1873 for his participation in the Catholic Socialist Movement. After being ordained in Luxemburg he was sent to Ecuador as a missionary in 1879 and transferred to Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1884. There, he collaborated with local leaders of the movement. Part of his work was to support the establishment of an insurance organization or mutual aid society, assisting the financial needs of workers. They published a newspaper, serving as the outreach arm for this organization, educating and uplifting the working class.