Plan your visit

By the Train Loads: Mexican Repatriation Movement in the Midwest, Part I

August 4, 2022

This is part one of a two-part series.

Within the last few years scholars, and the like, have continued to reflect on the complicated history of the United States; the known and not-so-well known. One of those events is the Mexican Repatriation Movement of the 1930s. Publicly, much of this narrative is focused on western border states like California. The total number of repatriates of Mexican nationality is estimated to be on the low end of 400,000. Due to recent research, that number is now estimated to be over 1 million. Federal records do not exist, except for a small number of formal deportations. Most returned, or “self-deported,” under coercive conditions directed by state agencies and funded by charitable means. After years of research, I have been able to piece together what this movement looked like in Indiana.

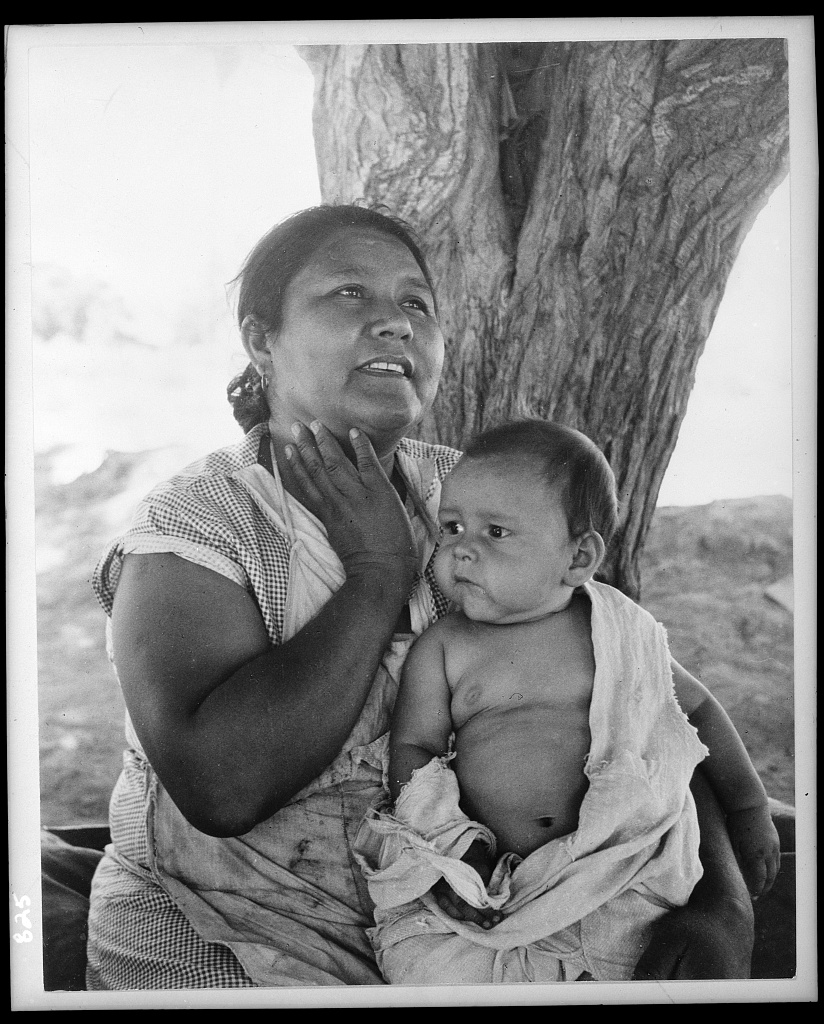

Mexican mother in California. “Sometimes I tell my children that I would like to go to Mexico, but they tell me ‘We don’t want to go, we belong here.'” (Note on Mexican labor situation in repatriation), 1935, Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information, Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

How it Began:

At the start of the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover addressed a joint session of Congress regarding the rapidly declining economy on December 2, 1930. One of his solutions was to further reduce visa availability to new immigrants and, “to more fully rid ourselves of criminal aliens,” especially those “in violation of immigration laws.”

Repatriation methods looked different from state to state and were based on the assurances of voluntary self-deportation through fear-inducing tactics like scare heading. This early tactic was implemented in California where immigration raids were regularly reported in local newspapers, splashed with sensationalized headlines. On January 26, 1931, California’s Charles P. Visel, head of the Los Angeles Citizen’s Committee on Coordination of Unemployment Relief sent a press release to all major English and Spanish-language newspapers in Los Angeles. This press release stated there would be future federal immigration raids assisted by the local police and county sheriff. On February 3, 1931, federal agents began to apprehend immigrants in Spanish-speaking neighborhoods, presumably comprised of ethnic Mexican residents. Mass deportations were executed without due process, and some were U.S. Citizens. In later reports, the St. Louis Dispatch noted that Hoover’s solutions resulted in “arrests without warrant, illegal search and seizures and deportation on insufficient evidence.”

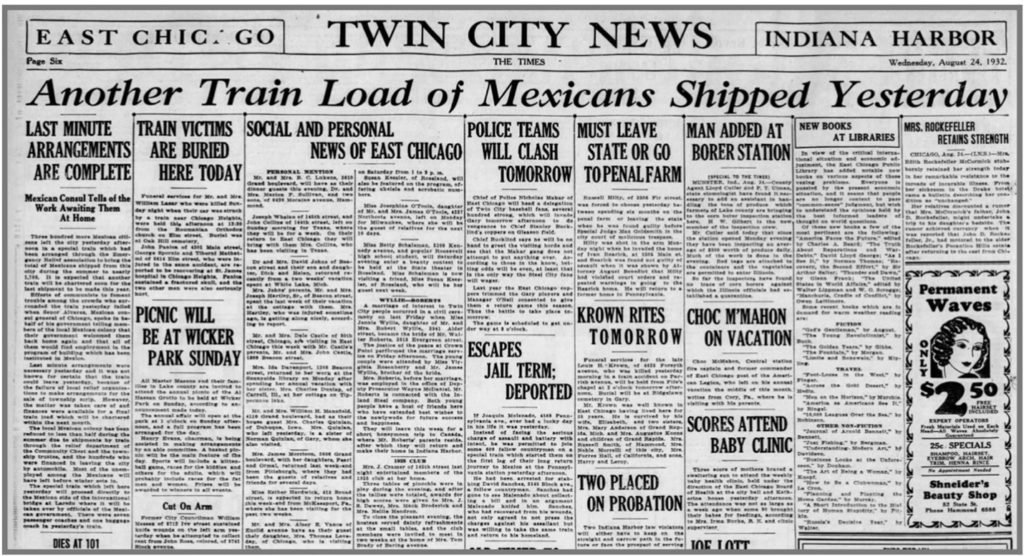

Last Minute Arrangements Are Complete: Mexican Consul Tells Them of the Work Awaiting Them at Home, Twin City News August 24, 1932

Repatriation in the Midwest: Northwest Indiana:

The 1930 U.S. Census National Origin number for Mexicans in Indiana was 9,642 with 9,007 living in Lake County in two areas. Indiana Harbor (East Chicago) had 5,343 Mexican residents, and 3,486 in Gary. They represented 20% of the foreign-born white population for Lake County. At this time, National Origin numbers did not account for U.S.-born citizens of Mexican ancestry; we can reasonably presume this number is larger than initially reported.

In the Midwest and in the State of Indiana, repatriation was subtly coercive, noted explicitly in local newspapers as a “relief program” in response to growing unemployment. Compared to the publicized raids in Los Angeles, this was a much more subversive approach. Ineligibility to be on relief rolls, intentionally withholding assistance to the Mexican colony and societal pressure fueled by the Great Depression only deepened this coercion. The aforementioned coupled with the national anti-Mexican sentiment only exasperated the need for this movement to be implemented in Indiana.

By the Numbers: Funders, Fares and Repatriates:

The Mexican Repatriation Movement was the nation’s answer to the “Mexican Problem.” Northwest Indiana saw the forced and coerced removal of 1,800 from Indiana Harbor (East Chicago) and 1,500 from the city of Gary. In total 3,330 Individuals from Lake County would be sent back to Mexico, 250 of those being children. These numbers were found in a 1932 report titled, The Story of Unemployment Relief Work in Lake County, Indiana. It was published by Walter J. Riley, Chairman of the Lake County Relief Committee and the Indiana Commission for Relief of Distress Due to Unemployment. In this report, section IV in the table of contents explicitly cites this relief program as the “Mexican Repatriation Movement.” More disturbingly, it noted the number of Mexican school-age children in East Chicago and the costs of educating them. Their repatriation was reported as a “saving of $21,000” and would be “saved annually for years to come.” Many resided in the “Block and Pennsy” neighborhood of Indiana Harbor, dubbed “Little Mexico” in The Calumet Region Historical Guide published in 1939.

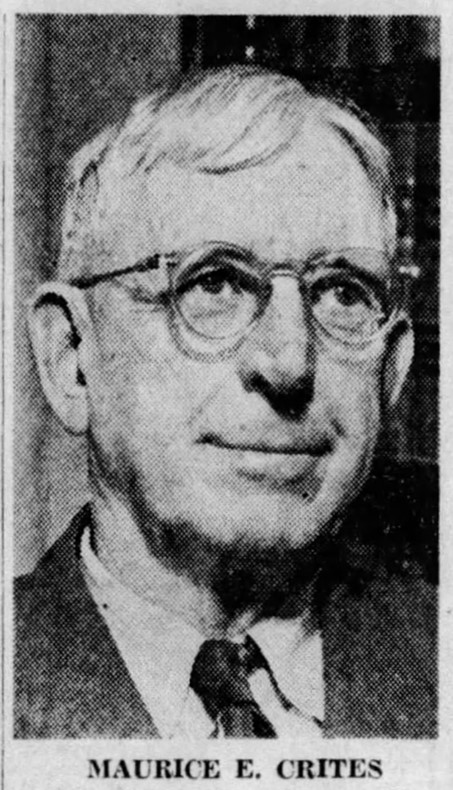

Maurice E. Crites, Ex-Judge, Dies, The Hammond Times, April 10, 1959

Initially, some relief agencies worked with small groups of individuals with repatriation assistance. This program of mass deportation relied on financial assistance provided by industries of East Chicago and Gary. Public philanthropic funds and local organizations would also contribute. Maurice E. Crites was the Lake Superior Court Judge (Lake County), who spearheaded the funding negations for this “relief program.” He previously was the City Attorney of East Chicago, President of the Chamber of Commerce, and the city’s Community Chest. At this time Judge Maurice E. Crites served as the head of the Emergency Relief association of the City of East Chicago. He negotiated with the industries of East Chicago, Gary and the Mexican consular office in Chicago. Concurrently, Mexico was initiating a “back to the land” movement to attract its ex-pats. Funds raised reduced the regular one-way fare to Mexico, from $49 to the charity rate of $15 for adults and $7.50 for children. It was reported that Mexico would provide free train fares at the border to individuals’ respective destinations. For some, this accommodation would be untrue.

The Foundation of the “Mexican Problem” In Northwest Indiana:

In the late 1910s, laborers would be attracted to Northwest Indiana’s bustling industrial lakefront corridor working in numerous rail yards, steel mills and their subsidiaries. Labor agencies and their agents were influential to the Midwestern Mexican diaspora. In 1918, the United States and Mexico would enter into a binational labor agreement (Departmental Order No. 52461/202) due to labor needs during World War I. The United States would solicit Mexican labor in the name of war relief for the first of two times in the 20th Century.

Throughout the 1920s a decline of available foreign workers at the border in Texas incited a series of laws called the Emigrant Agents Acts. Its goal was to restrict the flow of laborers out of Texas to other states, notably the Midwest. Significant financial fines and fees were placed on recruiting agents and bonds were placed on laborers, to ensure their return.

Further aided by bans on Chinese and other Asian groups, restrictive immigration quotas of select Europeans, coupled with the aftereffects of the Mexican Revolution; Lake County saw a period of exponential growth of the Mexican population in the 1920s. This growth resulted in the founding of religious anchor intuitions, a Mexican food company (present-day El Popular, Inc.), mutual aid and cultural organizations (present-day Unión Benéfica Mexicana), and the establishment of cultural traditions, all of which continue to thrive today. Indiana Harbor was the cultural hub of the two established Mexican colonies of Lake County and of Indiana.

Stay tuned for Part Two.