Purchase Tickets

Six Questions With Douglas Wissing, Author of “Gentleman in the Shadows”

May 8, 2020

From America’s post-World War II crusade to democratize Japan, the Korean War, nuclear standoffs with the Soviet Union, the Bay of Pigs, the Vietnam War, and Watergate, Benjamin C. Evans Jr. of Crawfordsville, Indiana, participated in the events that shaped his country’s and the world’s history.

In the IHS Press book “Gentleman in the Shadows,” author and award-winning journalist Douglas A. Wissing examines Evans and his career as an officer and top-level executive with the Central Intelligence Agency. When Evans retired in 1981 after more than two decades at this country’s foreign-intelligence service, the CIA awarded him the Distinguished Intelligence Medal, one of the agency’s highest honors.

Wissing took some time to answer questions about Evans and his work on his biography.

In examining Benjamin C. Evans Jr.’s life as a CIA official, what role did his life growing up in Crawfordsville, Indiana, play in his decision to pursue such a career?

Ben Evans grew up in a prosperous Hoosier family, staunch Methodists who were farm financiers. Based on the family archives, memoirs, and diaries kept by one of the family retainers, it appears that the Evans family’s conservative views, especially during the tumult of the Great Depression when a farm crisis wracked the Midwest, shaped young Ben’s political perspectives. From an early age he abhorred disorder and had a tropism toward maintaining the established social hierarchy.

Ben Evans began attending Culver Military Academy in northern Indiana as a young camper and rose to be the captain of the academy’s celebrated Black Horse Troop. At Culver, Evans was introduced to the military culture, which included training in the social skills that facilitate mutually beneficial interactions between the military’s upper echelons and America’s ruling classes. The connections that Evans made with other Culver cadets who were scions of wealthy families (including many international cadets, especially from Latin America) introduced Evans to the wider world of powerful people. His Culver experience led to his appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, and his subsequent work in U.S. Army intelligence. The rest, as they say, is history.

Was there one individual in his family or in his career that proved to be crucial for his development?

Ben Evans’s grandfather, Frank C. Evans, had an outsized influence on him. The family patriarch, Frank headed up the farm finance company that undergirded their social position. He was also a dapper bon vivant with a deep-seated love of nature. His country estate, Spring Ledge, just outside of Crawfordsville, was a beloved haunt of young Ben. There, under his grandfather’s tutelage, Ben reveled in nature and refined his social graces, including the equestrian skills that served him well at Culver and later in life. A family friend later wrote the two of them were kindred spirits.

During Ben Evans’s early military career in Occupied Japan, he served as aide-de-camp to General Eugene Harrison, who commanded a major swath of Japan around Kyoto during the post-World War II occupation. During the war, Harrison had served as an important military intelligence officer in the European theater, and later served on the government board that established the Central Intelligence Agency. This posting in Occupied Japan proved to be life-changing for Ben Evans. As part of his aide-de-camp responsibilities, he worked closely with the general’s family, which included precocious teenager Jan Evans. The two fell in love, and after a years-long courtship in Washington, DC, married in a society wedding. General Harrison later facilitated Ben Evans’s recruitment into the CIA.

How did his own family, particularly his wife, Jan, deal with a husband/father as a CIA official?

Jan Evans repeatedly told me, “I was a good CIA wife, I never asked questions.” Jan said if she did ask Ben questions about his work, he would say, “Now, Jan, is that on a need-to-know basis?” Through interviews with the Evans and other CIA family members, I learned that intelligence agency families pay an emotional price for these bifurcated lives. The biographer of CIA director Allen Dulles described him as “a guest in his own family home—amiable but detached”—the biographer termed it “emotional anesthesia.”

CIA spouses told me about the critical rite of passage when they told their children what they really did—they were spies, not minor diplomats or internationally itinerant mid-level business executives. “Breaking cover,” they termed it, akin to telling your kids the truth about Santa Claus or the facts of life. I was told the best time for the revelation was when the children in their early teens and posted in the United States. Some children reacted very badly. One intelligence official told me when he told his sixteen-year-old daughter, she shrieked, “You’re an assassin?”

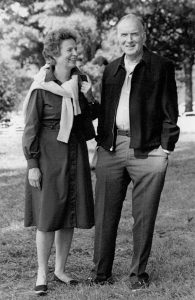

Ben and Jan, courtesy of Jan King Evans.

Evans played a large role in this country’s history during the 1960s and 1970s. Was there ever an incident that shook his faith in what he was doing?

Family lore tells of Ben Evans having an emotional breakdown. According to family stories, he threw up at his desk at the CIA after being told he had to organize an assassination of someone he knew. He had to take a leave of absence and see a CIA-vetted psychiatrist. A CIA psychiatrist told me that psychological breakdowns were not unusual in the intelligence services, where professional duplicity and black arts sometimes creates unresolvable ethical quandaries, especially for morally bound, duty-driven individuals, such as Ben Evans.

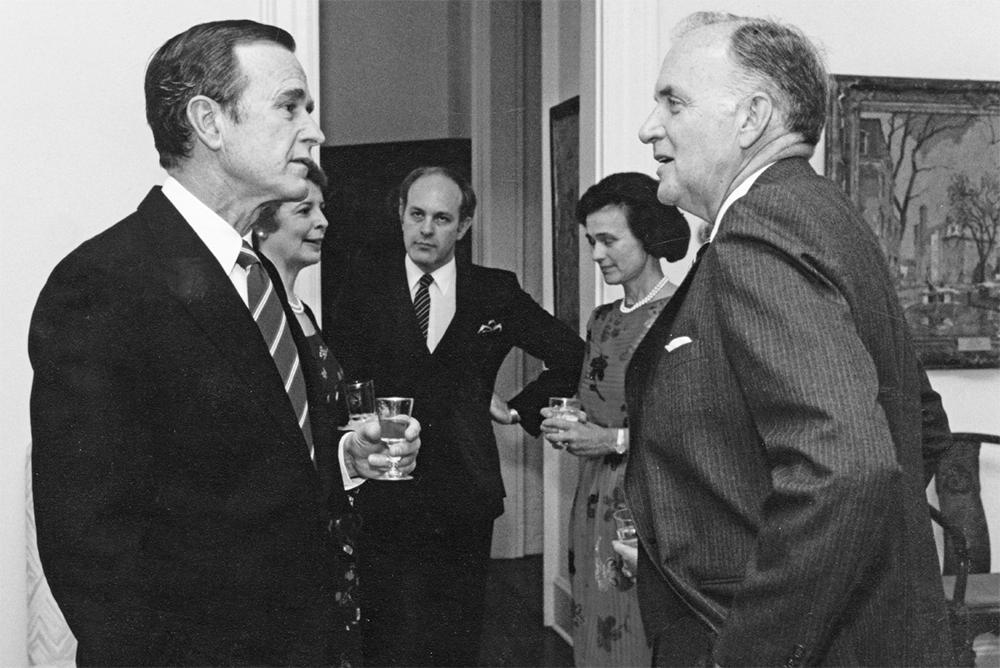

Vice President George Bush talks with Ben Evans. Jan King Evans is behind the vice president. Courtesy of Jan King Evans.

Because the CIA did not provide its “official” records for Evans, how did you go about piecing together Evans’ biography? Was there one source that played a critical role in your research?

The CIA refused to release classified documents relating to Ben Evans and his work in the agency—the spooks refused to even confirm Evans worked there, though he was a top executive through four presidential administrations and seven Directors of Central Intelligence.

So I had to utilize caches of declassified CIA documents that were in various repositories, such as National Security Archive at George Washington University. It was painstaking, time-consuming work to search these vast archives. The search yielded thousands of documents, but despite my best efforts at filtering it still was a needle-in-a-haystack research process. Added to that was the secondary research: mountains of histories, memoirs and biographies; obscure government documents about even more obscure subjects that were part of Ben Evans’ life. A lot of Internet work; a lot of time in the Indiana University libraries looking at Cold War-era books; lots of time interviewing CIA officers, staff and experts, as well as family members, including many hours of interviews with Jan Evans. I went down a lot of rabbit holes. I tell people that writing about the CIA career of Ben Evans was like putting together a jigsaw puzzle that had been through a shredder.

Can you talk about your writing process? Do you have a time you like to write, a place where you prefer to do your work?

A project like this envelops your life. I have an office at home, where I did much of the Internet research and the phone interviews. Reading the mass of books and documents happens everywhere—at the desk, on the sofa, in bed late at night and early in the morning. I always carried a book to read if I had a few minutes while eating lunch or waiting for an appointment. I flag books with post-it notes. Some books had so many flags they looked like porcupines. Yellow pads with notes; old-school 3 x 5 cards; docs on the computer; boxes and boxes of notated documents. Once I had the Gentleman in the Shadows structure determined, I could organize the material by chapter.

Eventually there came a time when all the parts and pieces of sundry information had to be organized and the first draft of each chapter written. For that tightly focused work, I went to the Monroe County Library in downtown Bloomington, where there is a quiet study room with big windows and long maple tables to spread out the reference material while I typed away on my MacBook. You won’t be surprised to learn my library hideout was the Indiana Room.