Purchase Tickets

Reckoning with Riverside

February 14, 2019

History Matters is a blog series where we’ll be talking about the things you’re not supposed to discuss at the dinner table – things that may make some people uncomfortable. These pieces of our history are there if you look but might not be top of mind or in a textbook. We often think of history on a larger scale, but let’s remember that history happened here. It happens every day. And it matters.

I’ve been thinking about my privilege a lot lately, specifically my white privilege.

I just finished White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngelo, a book I normally wouldn’t have picked up. I love fiction, and it’s what I generally read – contemporary literature, classic, historical fiction. I’ve been making an effort to read more nonfiction the last couple of years, and White Fragility was referenced in a book I read late last year – We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy by Ta-Nehisi Coates. His essays made me think more about what inequality looks like, how it is played out every day around the country, and whether I might be part of the ongoing problem unintentionally but nevertheless culpably.

So, I bought White Fragility immediately. And then I chickened out. It sat on my Kindle for several months begging me to step outside my comfort zone and face some ideas that may be difficult. DiAngelo begins, “I am mainly writing to a white audience; when I use the terms us and we, I am referring to the white collective. This usage may be jarring to white readers because we are so rarely asked to think about ourselves or fellow whites in racial terms.” Deep breath.

We all know this image of Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Little Rock Nine, and the white woman screaming at her, Hazel Bryan, taken in 1957 when Little Rock schools were integrated. (Image from Indiana University Bloomington Archives Photograph Collection)

From elementary school through high school, we cover aspects of the Civil War and the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s in history class. Here in the North, we’re taught simple narratives: The North fought the South over the issue of slavery in the Civil War and the civil rights movement took place in the South. It was about black students going to white schools, sitting at the front of the bus and sitting at the same lunch counter as white people. As DiAngelo puts it so well, “when white Northerners saw the violence black people – including women and children – endured during the civil rights protests, they were appalled. These images became the archetypes of racists. After the civil rights movement, to be a good, moral person and to be complicit with racism became mutually exclusive. … (These images of black persecution in the South during the civil rights movement of the 1960s also allowed Northern whites to position racists as always Southern.)”

The way we learn about these events in American history, at least in my northern city’s predominantly white suburb, reinforces this idea. It wasn’t about segregation in my neighborhood, my city, my state.

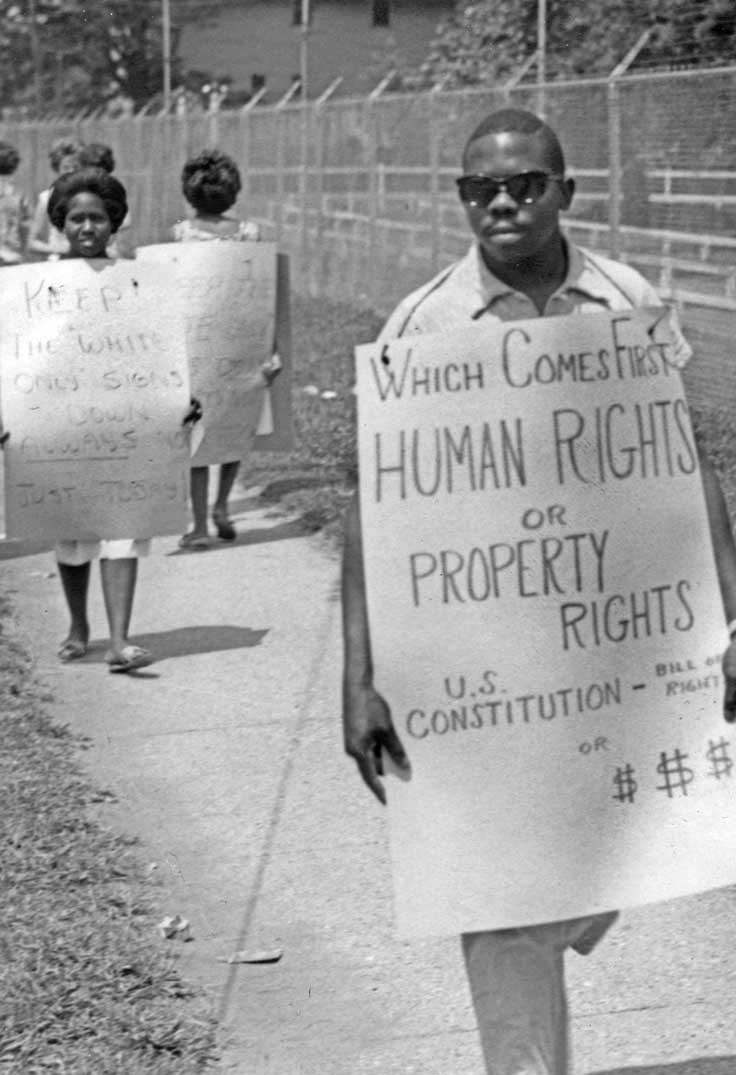

NAACP Youth picket outside Riverside Amusement Park in June 1962. (Indianapolis Recorder Collection, IHS)

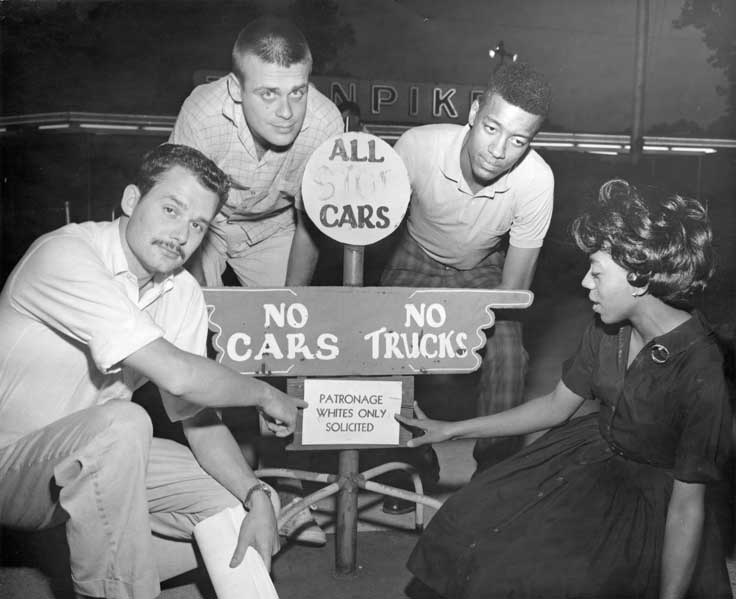

But the photos at the top of the page and right above, taken in 1962, tell a different story. A story that is much like the story of school segregation in Indiana – yes, it existed.

Riverside Amusement Park opened in 1904. But it wasn’t officially segregated until 1919. Schools in Indiana began segregating formally in the late 1920s and early 1930s. This step backward in racial equality is perhaps not surprising to everyone – the 1960s weren’t that long ago. Maybe you witnessed the picket line outside Riverside Park when NAACP youth carried signs asking, “What comes first: human rights or property rights?”

Riverside did allow African-Americans to enjoy the park – once a year – which is referenced in the sign the woman is carrying. It says, “Keep the white only signs down ALWAYS not just today.” In the February 2006 issue of Black History News and Notes, Paul R. Mullins notes that days in which blacks were allowed were called (cringingly) “Colored Frolic Day.” To the black community, the day became known as “milk cap day,” because each person had to offer up a milk cap to gain entrance.

These local stories are the ones we need to recall when we think about racism. It’s not a North/South issue. It’s an American issue. Will you be stepping out of your comfort zone soon? I want to hear your thoughts and start a meaningful conversation.

Further Reading

“Archaeology and Urban Renewal on Indianapolis’s Near West Side,” Black History News and Notes, Paul R. Mullins, February 2006, Vol. 28, No. 1.

Hoosiers and the American Story, James H. Madison and Lee Ann Sandweiss, IHS Press, 2014. See chapter 11, “Justice, Equality, and Democracy for All Hoosiers.”

Indianapolis Recorder Collection Images, Indiana Historical Society

“See Action Near on ‘White Only’ Sings at Riverside,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 21, 1962. Hoosier State Chronicles

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People to Talk About Racism, Robin DiAngelo, Beacon Press, 2018.

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, Ta-Nahisi Coates, One World, 2017.