Plan your visit

Maps: Tools to Enhance Understanding and Bring Research Alive

May 6, 2024

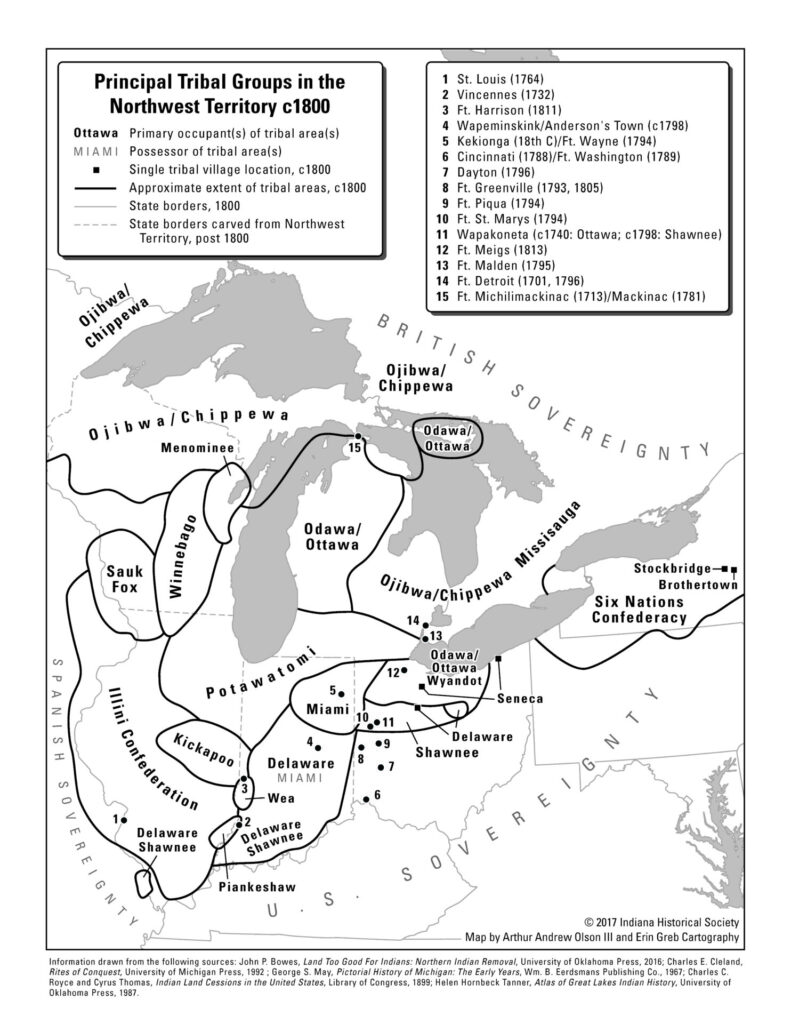

This map by Andy Olson and Erin Greb shows where Indigenous tribal groups were located in the Old Northwest Territory and beyond around 1800. There was much movement among bands within the main groups, and many villages included individuals or families from more than one tribe. The map shows the major groupings on the eve of the treaty era—the period when Indigenous People were forcibly removed to west of the Mississippi River. (Map by Arthur Andrew Olson III and Erin Greb Cartography, 2017, courtesy of Indiana Historical Society. It appeared in part 1 of Olson’s article series, “The 1818 Treaties of Saint Marys,” Connections, Fall/Winter 2017.)

A good map provides an understanding of a place or region that words cannot convey. Added to deep research and compelling writing, maps can help us see where long-gone forts, Indigenous villages, and early settler farms were located. They can show us how people moved from one place to another through forests, over mountains and hills, or on waterways from marshes to rivers. Maps with these representations can be invaluable when trying to learn where and how historic groups lived and how their environments shaped the opportunities and limits of their lives.

IHS Map Resources

The Indiana Historical Society has a vast collection of maps, dating from the 1500s. Each one shows how places, such North America or the Old Northwest, was perceived at a given time, dating back to the fifteenth century. They help us understand not just what was thought to exist in terms of topography, but also what peoples were inhabiting which areas.

When conducting research, one may have to use many different maps to follow the trails of people from long ago. One map may depict the colonial world, while giving only a vague idea of the rest of North America. Another one may give an idea of where different Indigenous groups lived at a particular point in time. A third may show us the routes the pioneers used to travel to the regions of Kentucky and the Old Northwest. Transportation maps are fascinating keys into the lives of early Hoosiers.

New Maps in Connections

What if we could pull all the disparate parts of the different maps together to more clearly see the world as it existed when early Americans, ancient Indigenous tribes, French fur traders, and English militia inhabited the Old Northwest together? Wouldn’t this give us a deeper understanding of the world our ancestors were creating, the challenges faced on all sides, the realization that everyone there was fighting for survival, family, tribe, country—or a combination of some of these goals? In two different series of articles for Connections magazine, author Andy Olson encountered the need for such maps and set about creating them. His first series, on the 1818 Saint Marys Treaties, tells the story of the different tribes involved in the first treaties that initiated the removal of the Indigenous Peoples from the eastern part of the fledgling United States.

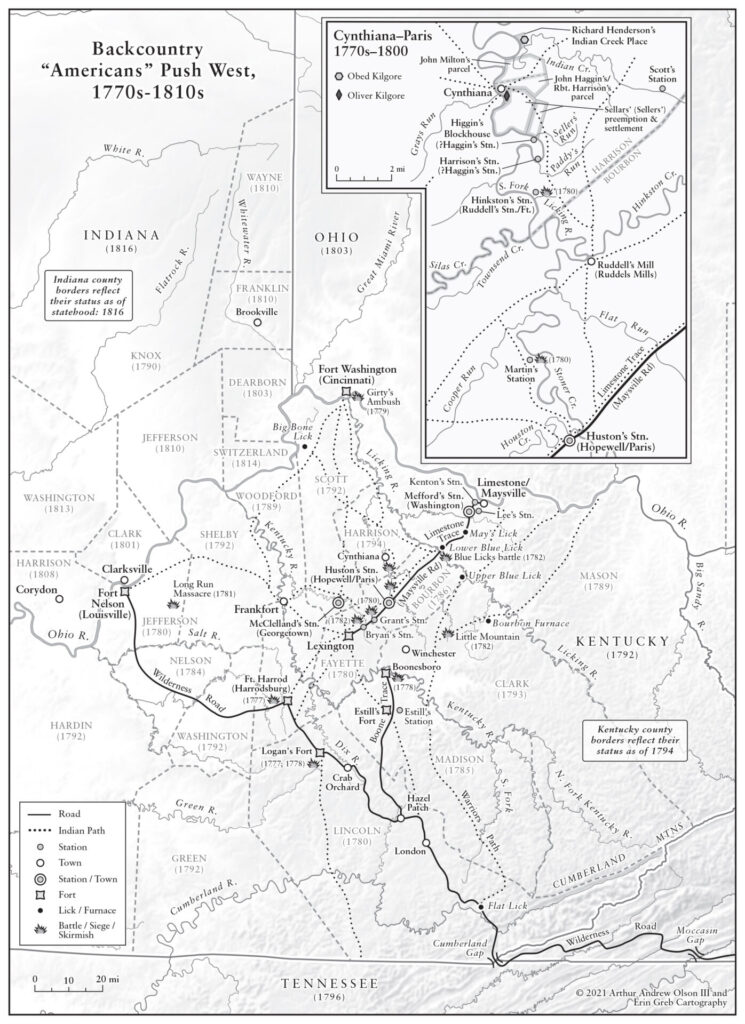

The second article series, available in the Members’ Section of the IHS website, is titled “The History Behind Your Hoosier Genealogy.” Featured in six issues of Connections from Fall/Winter 2020 through Fall/Winter 2023, it contains uniquely crafted maps by Olson and Erin Greb Cartography. Their maps guide us through the early-eighteenth-century backcountry of Pennsylvania, down the Ohio River, into Revolutionary-era Kentucky forts, up through the Indigenous country of Ohio, and into the territory and then fledgling state of Indiana. The detail and clarity of the Olson-Greb maps is stunning and highly useful to historical and genealogical researchers.

Throughout the Revolutionary War, battles, skirmishes, or sieges—led or endorsed by the British and nearly always with Indigenous warrior participation—occurred with high frequency in Kentucky. The goal was to confine American settlement east of the Appalachian Mountains, formally known as the 1763 Proclamation Line. This series of invasions was intended to disrupt permanent pioneer encampment. Even as late as the War of 1812, such raids continued to be a threat. American soldiers and settlers built a series of lightly fortified “stations” and more heavily defended forts to protect settlers from such threats. Because the Limestone (Buffalo) Trace/Maysville Road, which served as a primary avenue for pioneer migration to Kentucky’s interior, was closer to Indigenous populations just north of the Ohio River, stations along this artery were more vulnerable to attack than migratory movement along the more southerly Wilderness Road. (Map courtesy of Arthur Andrew Olson III and Erin Greb Cartography, ©2021; originally scheduled to appear in part 3 of Olson’s article series, “The History Behind Your Hoosier Genealogy,” Connections, Spring/Summer 2022, available in the Basile History Market)

A Mapmaker’s Perspective

Recently, Andy and I took a pause from writing and editing his article series to talk about the treasure trove of maps he and Erin Greb have been producing. Andy opened up and told me about his love of maps and about his work with Erin to create the collection of maps for his publication projects:

Throughout my life I have had an interest in maps and what they convey. Long before I began research and writing, I had accumulated a variety of atlases to help me better understand and interpret the world around me. Most people of my generation were familiar with the Nystrom pull-down world maps, prevalent in elementary school classrooms. These whetted my appetite for visual presentations of the world. Then there were the Rand McNally Road Atlases, which, for many of us, provided our first exposure to using maps in our everyday lives—most often for family road trips. The World Book Encyclopedia of the late 1950s was also ever present in my household. Its full-color maps, tailored for school-age children, often incorporated an underlying base map overlaid with flexible see-through sheets that added layer after layer of additional information.

My family also subscribed to National Geographic magazine, wherein maps helped orient readers to different parts of the globe, adding insight to articles about today’s communities as well as those about the generations who lived before us. National Geographic also provided wall-sized political, physical, and specialized maps.

To this day, the large 1981 National Geographic Atlas of the World, sits on my family room table alongside the Indiana Historical Society’s Mapping Indiana book from 2015, offering a history in maps of the Hoosier state. Still scattered around my home are atlases and standalone maps produced over the past fifty years—from those I used to navigate during numerous business and pleasure trips to those providing unique presentations of historical expeditions of discovery made around the world. I have always loved maps.

Thus, it is not surprising that as I began my “second career” of historical research and writing, I quickly realized that the creation of specialized maps to help guide readers would need to become an integral part of clearly conveying the stories. My first project was a book on one of Indiana’s earliest railroads, Forging the Bee Line Railroad (Kent State University Press, 2017). Using the Internet in 2015, I sought a cartographer suited to the task. Fortunately, I came upon Erin Greb Cartography. On Erin’s company website she provided substantial examples of her work and the types of clients for whom she worked. Her strong academic background in geography was complemented by subsequent employment as a textbook map designer with such organizations as MapQuest Publishing and as a cartographer at Penn State’s Department of Geography, where she produced scholarly maps. Erin had made the jump to freelance work in 2007, providing me with the opportunity to engage her on a project-by-project basis. It has proved to be an incredibly important professional relationship.

Erin has taken my myriad of historical discoveries and translated them into accurately mapped portrayals, balancing my desire for detail with her artistic skills, while providing sufficient background information without cluttering the final products. Her maps are striking yet easy to interpret. As she says about herself: “I think in maps. . . . I just can’t get away from it. And I guess that’s why I became a cartographer.” On her website, Erin suggests the passion for her work “comes from bringing all sorts of data together and telling a visual story through the art of cartography.”

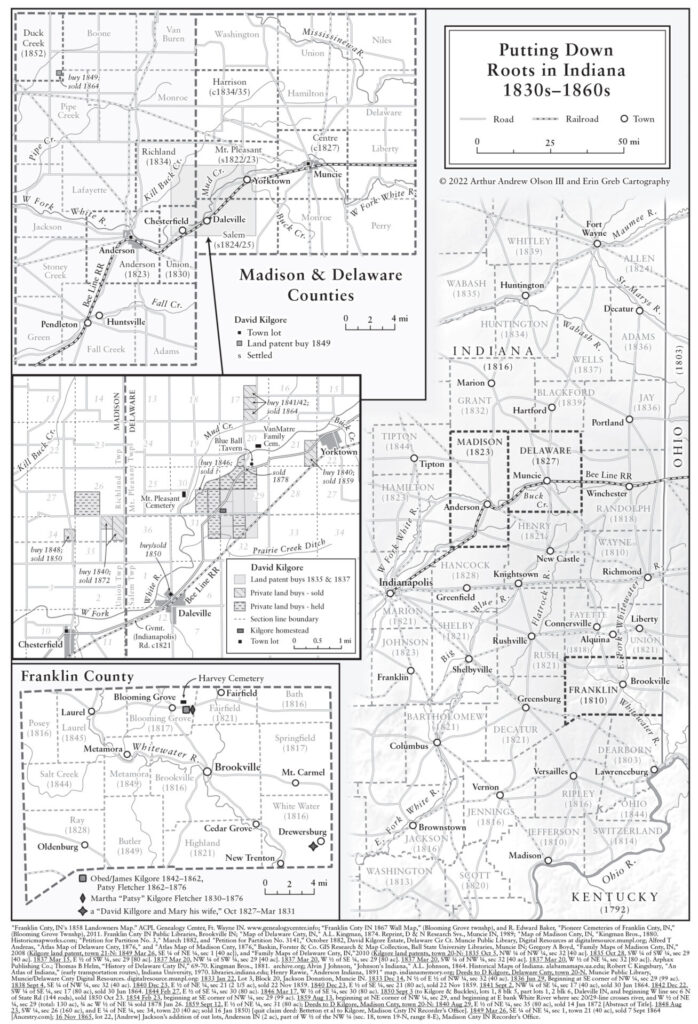

Since our initial work on the railroad book, for which she created or annotated eight maps, Erin has created a variety of maps for my two Connections series. Our work has evolved over the past eight years to include representations of several sub-maps integrated onto a single page (or two-page spread). Ours is an iterative back-and-forth process, often resulting in five or more versions before finally arriving at a mutually satisfying result. Without her skills, it would have been difficult to tackle and interpret the level of detail conveyed in my articles. Erin’s work has brought my articles to life. I am both grateful and amazed by what she has accomplished.

The IHS Press is also grateful and amazed by the maps made by Erin Greb and Andy Olson. His work to discover the day-to-day worlds in which our ancestors traveled informs Erin’s work. Together, their maps provide much-needed windows onto the transportation routes, villages, forts, and people who lived in our region before us, paving the way for the world we live in today.

The initiation of land auction sales of “New Purchase of Indiana” parcels in Franklin County’s Brookville, beginning in 1819, led to a large influx of pioneers first to this land office town and county, and then to acquired parcels to the north and west. Counties such as Madison and Delaware were soon organized around two former villages of the removed Delaware (Lenape) Indigenous Nation. In these two instances, Anderson (named after chief Anderson [Kikthawenund]) and Muncie (named for the Munsee/Muncee tribal group of the Lenapes) became their respective county seats. Enterprising new arrivals soon acquired land from both the government—known as “land patents”—and private individuals. (Map courtesy of Arthur Andrew Olson III and Erin Greb Cartography, ©2022; published in part 5 of Olson’s article series, “The History Behind Your Hoosier Genealogy,” Connections, Spring/Summer 2023)