Plan your visit

Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Indianapolis, and Slaughterhouse-Five

August 14, 2020

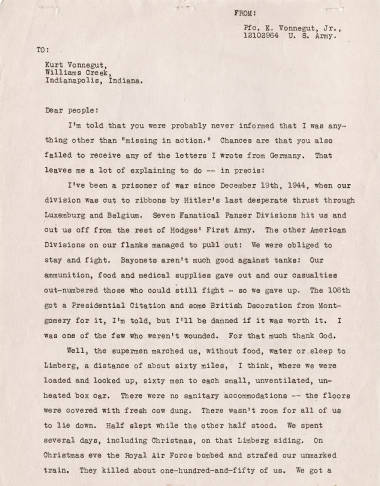

On May 29, 1945, twenty-one days after German forces had surrendered to the victorious Allied armies, a father in Indianapolis received a letter from his son who had been listed as “missing in action” following the Battle of the Bulge. The young man, an advance scout with the 106th Infantry Division, had been captured by the Germans after wandering behind enemy lines for several days. “Bayonets,” as he wrote his father, “aren’t much good against tanks.”

Eventually, the Indianapolis native found himself shipped to a work camp in the open city of Dresden, where he helped produce vitamin supplements for pregnant women. Sheltered in an underground meat storage locker, the Hoosier soldier survived a combined American/British firebombing raid that devastated the city and killed thousands of men, women, and children. After the bombing, the soldier wrote his father, “we were put to work carrying corpses from air-raid shelters; women, children, old men; dead from concussion, fire or suffocation. Civilians cursed us and threw rocks as we carried bodies to huge funeral pyres in the city.”

Letter from Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. to Kurt Vonnegut, May 29, 1945; Indiana Historical Society, SC1509

Freed from his captivity by the Red Army’s final onslaught against Nazi Germany and returned to the United States, the soldier — Kurt Vonnegut Jr.— attempted for many years to put into words what he had experienced during that horrific event. At first, it appeared to be a simple task. “I thought it would be easy for me to write about the destruction of Dresden, since all I would have to do would be to report what I had seen,” Vonnegut noted.

It took Vonnegut, who died on April 12, 2007, more than 20 years, however, to produce Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade, A Duty-Dance With Death, published in 1969. The book proved to be worth the wait. Released to an American society struggling to come to grips with its involvement in another war, in a small Asian country named Vietnam, Vonnegut’s novel struck a nerve, especially with young people on college campuses across the country. Although its author termed the work a “failure,” readers did not agree, as Slaughterhouse Five became a best seller and pushed Vonnegut into the national spotlight for the first time.

His experiences always seemed to help shape what Vonnegut wrote. Especially important was his life growing up in Indianapolis. Revisiting his birthplace in 1986 to deliver the Indianapolis–Marion County Public Library’s annual McFadden Memorial Lecture, Vonnegut told a North Central High School audience, “All my jokes are Indianapolis. All my attitudes are Indianapolis. My adenoids are Indianapolis. If I ever severed myself from Indianapolis, I would be out of business. What people like about me is Indianapolis.”

Born on November 11, 1922, Kurt Vonnegut Jr. was the second son of Kurt, an architect, and Edith (Lieber) Vonnegut. Fourth-generation Germans, the Vonnegut children were raised with little, if any, knowledge about their German heritage: a legacy, the junior Vonnegut believed, of the anti-German feelings vented by Americans during World War I. The anti-German feeling so shamed Kurt’s parents, he noted, that they resolved to raise him “without acquainting me with the language or the literature or the music or the oral family histories which my ancestors had loved. They volunteered to make me ignorant and rootless as proof of their patriotism.”

Vonnegut’s time in Indianapolis’s public schools started him on the path to a writing career. Attending Shortridge High School from 1936 to 1940, Vonnegut, during his junior and senior years, edited the Tuesday edition of the school’s daily newspaper, The Shortridge High School Echo. He developed an easily understood writing style, explaining that he wrote for his “peers and not for teachers, it was very important to me that they understood what I was saying.”

Shortridge Daily Echo Editors, Circa 1940; Indiana Historical Society, M0482

After graduating from Shortridge, Vonnegut went east to college, enrolling at Cornell University. Vonnegut’s days at the eastern university were interrupted by America’s entry into World War II. “I was flunking everything by the middle of my junior year,” he admitted. “I was delighted to join the army and go to war.” In January 1943 he volunteered for military service. Although he was rejected at first for health reasons (he had caught pneumonia while at Cornell), the army later accepted him and placed him in its Specialized Training Program.

Vonnegut eventually ended up as a battalion intelligence scout with the 106th Infantry Division, which was based at Camp Atterbury, just south of Indianapolis. It was while he was with the 106th that he met and became friends with Bernard V. O’Hare, who joined Vonnegut as a prisoner of war in Dresden and would go on to play a large role in the genesis of Slaughterhouse-Five. On Mother’s Day in 1944 Vonnegut received leave from his duties and returned home to find that his mother had committed suicide the previous evening. Edith Vonnegut had grown increasingly depressed over her family’s lost fortune and her inability to remake that fortune by selling fiction to popular magazines of the day.

Three months after his mother’s death, Vonnegut was sent overseas just in time to become engulfed in the last German offensive of the war – the Battle of the Bulge. Captured by the Germans, Vonnegut and other American prisoners of war were shipped in boxcars to Dresden, the first “fancy city” he had ever seen, Vonnegut said. As a POW, he found himself quartered in a slaughterhouse and working in a malt-syrup factory. Each day he listened to bombers drone overhead on their way to drop their explosives on other German cities.

On February 13, 1945, the air raid siren went off in Dresden and Vonnegut, some other POWs and their German guards found refuge in a meat locker located three stories under the slaughterhouse. “It was cool there, with cadavers hanging all around,” Vonnegut said. “When we came up the city was gone.”

Freed from captivity by Russian troops, Vonnegut returned to the United States and married Jane Marie Cox on September 1, 1945. The young couple moved to Chicago where Vonnegut worked on a master’s degree in anthropology at the University of Chicago. While going to school, he also worked as a reporter for the Chicago City News Bureau. Vonnegut left school to become a publicist for General Electric’s research laboratories in Schenectaduy, New York.

While working for GE, Vonnegut began submitting stories to mass-market magazines. His first published piece “Report on the Barnhouse Effect,” for which he received $750, appeared in Collier’s February 11, 1950, issue. “I think I’m on my way,” Vonnegut wrote his father. “I’ve deposited my first check in a savings account . . . and will continue to do so until I have the equivalent of one year’s pay at GE. Four more stories will do it nicely… I will then quit this goddamn nightmare job, and never take another one so long as I live, so help me God.”

Vonnegut quit his job at GE in 1951 and moved to Cape Cod to write full time. His science background — the course he took in high school and college and his work at GE — influenced his work. When it came time for him to respond to life as a writer, he responded to it as a scientist would. His novels included Player Piano (1952), The Sirens of Titan (1959), Mother Night (1962), Cat’s Cradle (1963), and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965).

After briefly touching on his World War II experience in other his other books, Vonnegut in 1969 delivered to the reading public a book dealing with the Dresden bombing. Slaughterhouse Five is the story of Billy Pilgrim, like Vonnegut, a young infantry scout captured by the Germans in the Battle of the Bulge and taken to Dresden where he and his other prisoners survive the February 13, 1945 firebombing of the city. Pilgrim, whose character is modeled on a GI named Joe Crone, a fellow prisoner of war from the 106th Division who died in Dresden, copes with his war trauma through time travels to the planet Tralfamadore, whose inhabitants have the ability to see all of time — past, present, and future — simultaneously. The book is so short, jumbled and jangled, Vonnegut explained, because “there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre. Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again.”

Although Vonnegut considered the book a failure — it had to be, he said, as it “was written by a pillar of salt”—the public disagreed. Written during the height of the Vietnam War, Slaughterhouse Five’s compassion in the face of terrible slaughter struck a nerve with an American populace trying to come to grips with the war and a society that seemed to be, at best, headed for major changes. After all, Vonnegut’s book was released during a year that saw such shocking events as Neil Armstrong taking the first step on the moon, the New York Mets winning the World Series, more than a half a million youngsters gathering on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in New York for a music festival called Woodstock, and the uncovering of a massacre of Vietnamese civilians by American troops in a village named My Lai.

Reflecting about his war experience in Dresden, Vonnegut, who died on April 11, 2007, responded by claiming that only one person on the entire planet benefited from the bombing. “The raid,” Vonnegut said, “didn’t shorten the war by half a second, didn’t free a single person from a death camp. Only one person benefited — not two or five or ten. Just one.” That one person was Vonnegut who, according to his own reckoning, received over the years about five dollars for every corpse from the sales of Slaughterhouse-Five.