Plan your visit

Indigenous History in Indiana: Treaties and the Complexity of Language Preservation

November 15, 2021

November is Indigenous History month. Indigenous communities in present-day Indiana, existed for generations, several times over, before European contact. And they continue to exist today. Early European colonizers and American settlers came west into the Northwest Territory, to occupy land now known as the State of Indiana. Indigenous communities that existed before colonization were the Kickapoo, Lenape (Delaware), Miami (Myaamia), Piankashaw, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Wea and Wyandot or Wyandotte (Wendat). The first European contact with these tribes was in the late 1600s with French fur traders.

Potawatomi Chief, (phonetic name) Me-no-quet, 1827 Treaty of Fort Wayne. Portraits of the Most Celebrated Chiefs of the North American Indians. Philadelphia: Lehman & Duval, 1836, E89.L67 1836

What we know of these indigenous communities is through the recollection and written work of those who made their way out west; religious missionaries and those who sought out to occupy Indian land. Indigenous culture and tribal history, especially their spoken languages, were passed down orally and through storytelling. In short, before European contact, it was not a written language. With colonization, treaties, removal, and coerced assimilation, much was lost to future generations through systematic erasure.

The first treaty established in our state, prior to statehood, was the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. This treaty granted early settlers to occupy Indian land north of the Ohio River. Later, William Henry Harrison, first Governor of the Indiana Territory, brokered numerous treaties to purchase Indian-owned land. In 1818 the Treaty of St. Mary’s with the Delaware, Miami, Potawatomi, Wea and Wyandot acquired the largest swath of land, eight million acres, primarily in central Indiana. Subsequently this treaty, in its written form, set the framework for future removal. In 1830, after the federally mandated Indian Removal Act, the Delaware, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Piankashaw, Shawnee, Wea were mostly removed from Indiana. Some Potawatomi and Miami tribes remained, due to previous treaty agreements. In a few short years after the federal Indian Removal Act, both tribes ceded their treaty-protected land and relocated to a reservation in Osawatomie, Kansas. In 1838, a group of 859 Potawatomi began what is known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death. Only 817 survived the 660-mile trek, 28 of those deaths were children.

However, what is lesser known is that not all were systemically removed by this federal mandate. Those who remained were a small population of landowners. Due to this small size; their culture, traditions, especially their languages eventually died out. A more appropriate term, articulated to me by our state Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, Diane Hunter, that certain languages did not die out, but simply went to sleep. Today, the Miami language has been awakened and there is an academic study center dedicated to the preservation of Miami culture and language at the Myaamia Center at Miami University in Ohio.

Remarkably, in our collection, we have several books dating from the early to mid-1800s that are written in the Lenape (Delaware) and Potawatomi languages. This would be the earliest known publication of these indigenous languages in our collection.

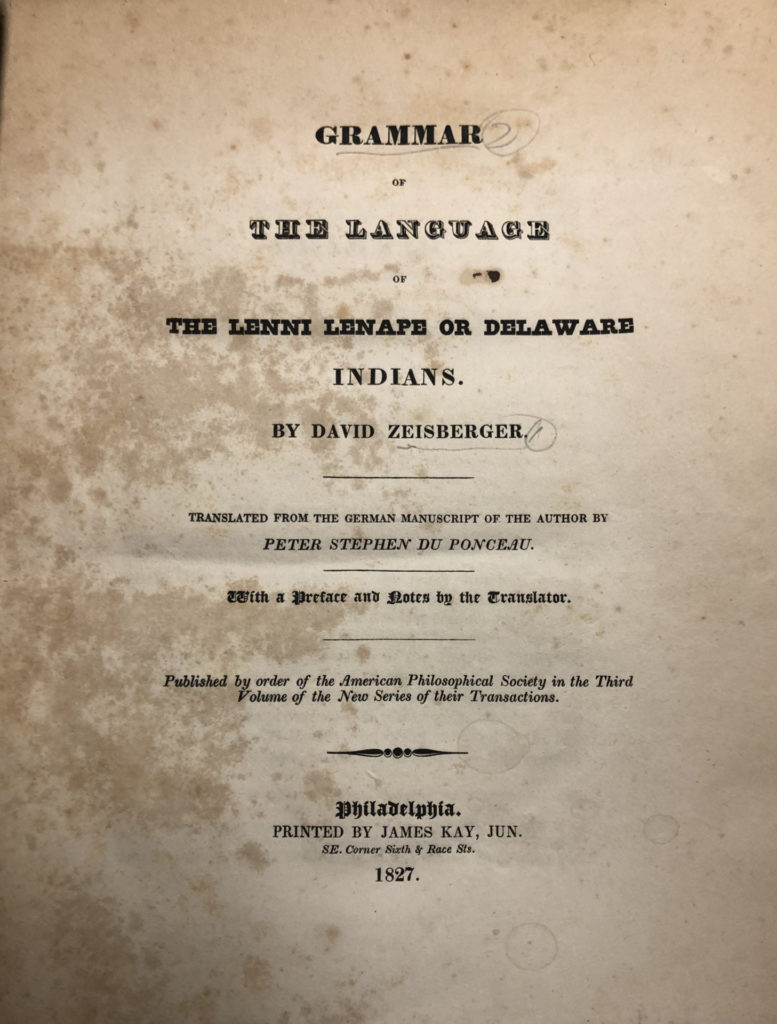

The books in our collections were written through the perspective of religious missionaries, of Catholic and United Brethren denominations. Two books were written by a Christian missionary of the United Brethren, David Zeisberger. He was a Moravian clergyman and missionary who lived among indigenous tribes in Ohio. He worked within these communities preaching the gospel. He was a pioneer of written indigenous languages, most notably of the Lenape (Delaware) language. One of the two Zeisberger publications in our collection is a hymnal titled, A Collection of Hymns: For the Use of the Delaware Christian Indians, printed in 1847. The other is a grammar book titled, Grammar of the Language of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware, printed in 1827. Both are translated from English or German texts.

Grammar of the language of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians. PM1032.Z3 1827

David preached and lived among indigenous tribes and Indian converts for sixty years until his death. In the preface of the grammar book, it noted the lack of written sources of indigenous languages and the increasing interest among others, in particular religious missionaries.

“It is but lately that the forms of the languages of the American Indians have begun to attract attention; I am satisfied that the more they are known, the greater astonishment they will excite in unprejudiced minds.”

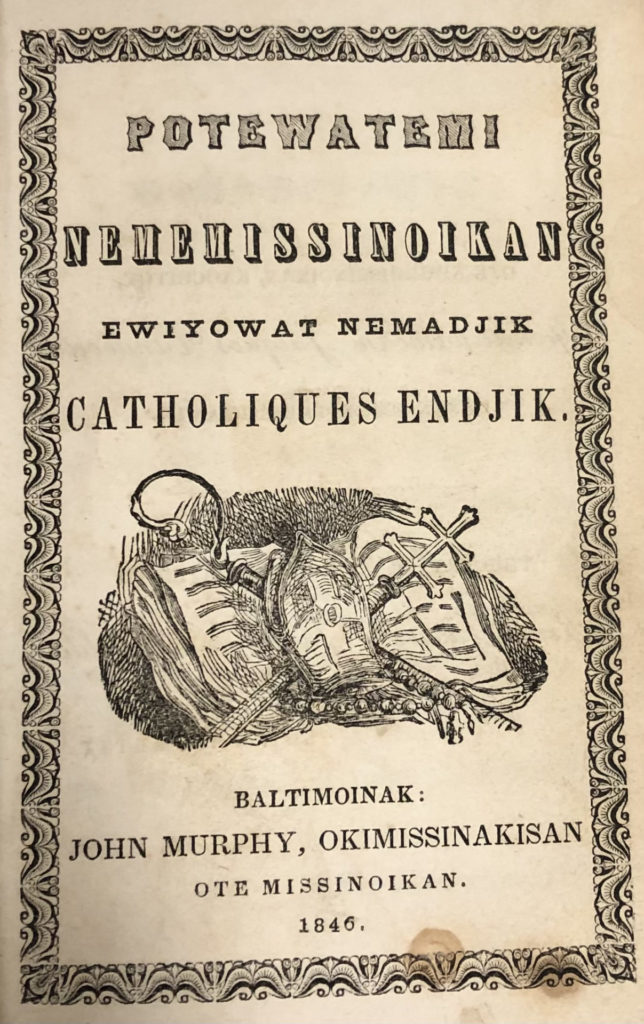

Also in our collection are two Catholic prayer books, entirely in the Potawatomi language. The first is Potewatemi Nemeussuinukan Ewiyowat Nemadjik Cathoiliques Endjik, by Christian Hoecken, printed in 1846. And Potewatemi Nemëmiseniükin Ipi Nemënigamowinin by Maurice Galliand, printed in 1868.

Potewatemi Nememissinoikan Ewiyowat Nemadjik Catholiques Endjik PM2191.Z71 – 1846

These texts are extraordinary examples of language preservation of indigenous languages. Present and ongoing discoveries of the exploitation of Indigenous communities in Canada and the United States add a layer of uncomfortable complexity to it all. History is complex and at times, uncomfortable. By leaning into this discomfort, it gives us the space to learn and grow.