Purchase Tickets

Airing Our Dirty Laundry

January 25, 2019

This blog is the inaugural in a series we’re calling History Matters. We’ll be talking about the things you’re not supposed to discuss at the dinner table – things that may make some people uncomfortable. These pieces of our history are there if you look but might not be top of mind or in a textbook. We often think of history on the larger scale, but let’s remember that history happened here. It happens every day. And it matters.

A building used to sit on the southeast corner of Raymond Street and Bluff Rd. The building is long gone, but I remember my dad telling me when I was young, “That’s where they send unwedded pregnant mothers.” I don’t know the name of the building, but I was hoping you could send me some information on it, if possible. – J.A.

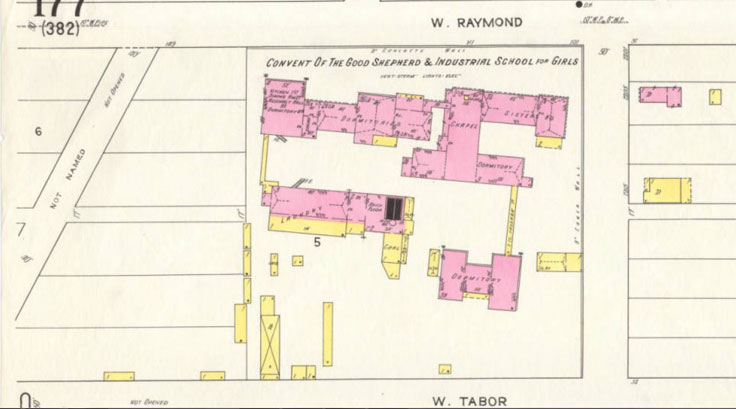

A little over a year ago, this question appeared in our library inbox. None of us had heard of the building, so I looked up the location in our collection of Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map depicting the Convent of the Good Shepherd, 1915. (Digital image from Indianapolis Sanborn Map and Baist Atlas Collection, University Library, IUPUI)

It was a convent, an unsurprising answer. The Catholic Church, after all, has a long history of working with unmarried mothers. But my insides iced over at the sight of the smaller building on the southwest corner of the complex marked “Laundry.” That was when I knew we were dealing not with a maternity home or adoption agency but a prison.

The historical ties binding Catholic convents and laundries are terrible and peculiar. In the 18th century, institutions that are now known as Magdalene Laundries began to creep across western Europe. Overseen by female religious orders, they ostensibly provided refuges where “fallen women” could metaphorically wash their sins away. In reality, they were government-sanctioned, church-run prisons where unpaid inmates labored in commercial laundries.

Magdalene Laundries incarcerated girls and women for years – some even for life – for so-called moral crimes such as prostitution and adultery. A crime was not always even necessary. Being an orphan, or unmarried and pregnant, was often enough to ensure a girl ended up there. Conditions were harsh, talking was mostly forbidden, and corporal punishment was the norm. Women who gave birth in the laundries had their children forcibly taken from them and placed for adoption. Some lost their sanity in addition to their freedom.

Magdalene Laundries especially flourished in Catholic Ireland, where the last one didn’t close until 1996. The laundries’ legacy there is well-known, and in 2018 Pope Francis formally apologized to the citizens of Ireland for the crimes committed against them, saying, “May the Lord … give us strength so this never happens again, and that there is justice.”

Those same crimes occurred here in Indiana, yet few people know of them. The Sisters of the Good Shepherd opened their first American Magdalene Laundry in Louisville in 1843. Dozens more followed, including the Indianapolis Convent of the Good Shepherd and St. Joseph Laundry in 1873. Like other cities who hosted the Sisters, Indianapolis threw the separation of church and state out the window, frequently sending women to work at the laundry in lieu of prison.

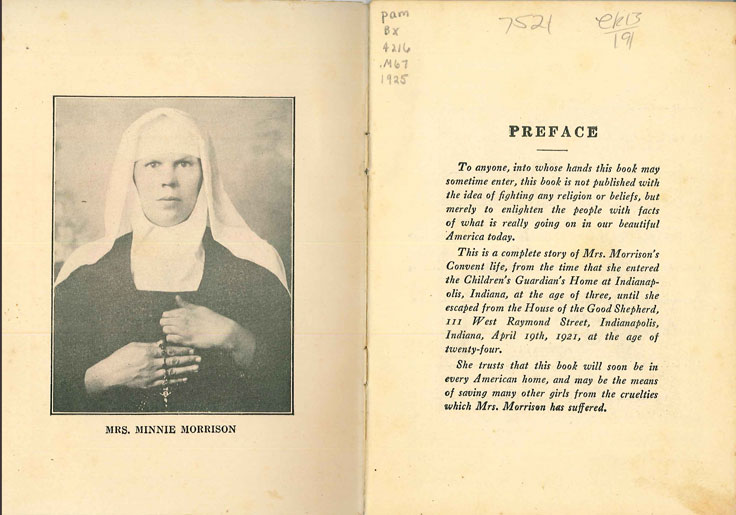

Pages from the Life Story of Mrs. Minnie Morrison: Awful Revelations of Life in Convent of Good Shepherd, Indianapolis, Ind. (A True Story), 1925, in which Morrison contends that she was held unjustly for years and abused by convent staff.

It was only in 2013 that students in the Indiana Women’s Prison higher education program began to uncover the details of whom our local government sent to the laundry and why. While researching the history of their own institution, they noticed a curious fact – for the first 24 years of the Women’s Prison’s operation, not a single inmate had been sent there for sex crimes. It was not that no one had been convicted of such crimes, as it turned out. It was that judges had sentenced them all to work at the laundry. The nuns’ eight-foot concrete wall was not there to keep the secular world out of the convent. It was there to keep people in.

The Sisters and their laundry remained at 111 West Raymond Street for more than seven decades, and last appeared in the Indianapolis city directory in 1955. Eventually, the complex was demolished. Nothing at the site now marks the trials, hopes and sufferings of the women who lived there.

The Sisters of the Good Shepherd no longer run laundries where women are confined against their will. They dedicate themselves to serving women and girls in need through the operation of women’s shelters, halfway houses, job training centers and other institutions.

Top image: Sisters of the Good Shepherd Altar, 1943. (Larry Foster Collection, Indiana Historical Society)

For Further Reading

Life Story of Mrs. Minnie Morrison: Awful Revelations of Life in Convent of Good Shepherd, Indianapolis, Ind. (A True Story), 1925, Minnie Morrison. You can find this book in the collections at Indiana Historical Society.

For the Indiana Women’s Prison students’ full article on the St. Joseph Laundry in Indianapolis, click here.