Purchase Tickets

A Civil War Letter from Libby Prison

May 15, 2020

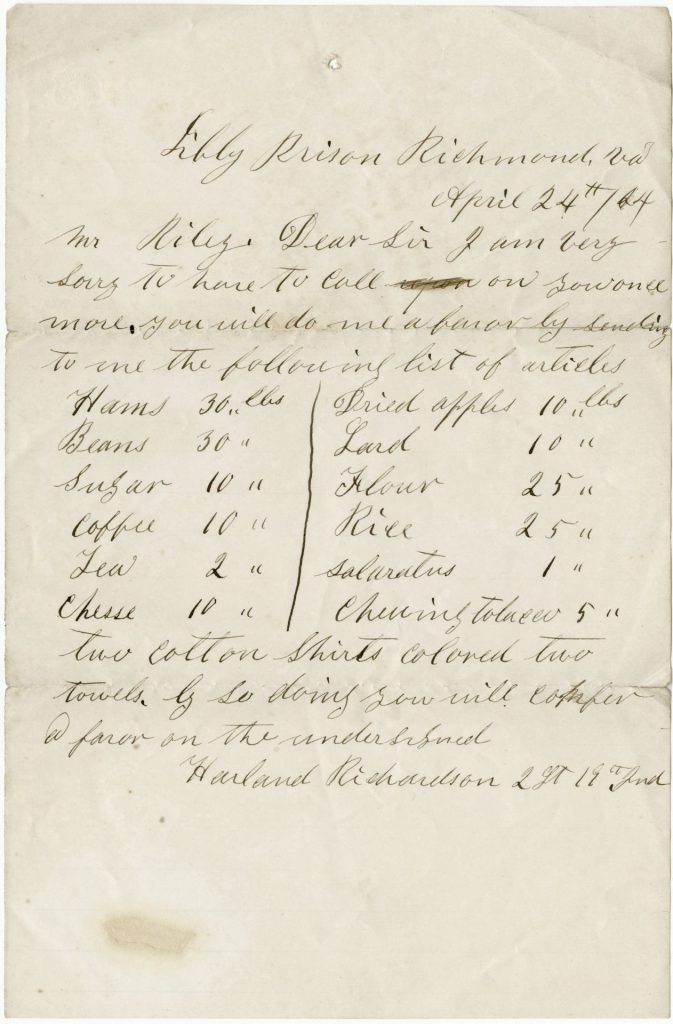

After 40 years of processing manuscript collections, I can still find some that excite me. Such is the case with a recent Civil War letter we acquired, a letter from Lieutenant Harland Richardson of the 19th Indiana (Iron Brigade) to a Mr. Reilly on 24 April 1864.

This is particularly exciting for anyone interested in Civil War history for several reasons. Richardson was in the 19th Indiana which formed part of the Iron Brigade, probably the best fighting unit in the Union Army. He was taken prisoner at the Battle of Gettysburg where the brigade suffered a 64% casualty rate as compared to 28% for the rest of the Union Army. The second aspect is that it was written from the notorious Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, generally regarded as the second worst prison in the South behind Andersonville. And third is the content of the letter itself, while not exciting, is historically significant.

Libby Prison, April 1864

Harland Richardson (1833-1925) was born and spent most of his adult life farming in Perry Township in southern Marion County, Indiana, a profession he was quite successful at. In July 1861, he enlisted in Company F of the 19th Indiana and rose through ranks to Second Lieutenant. Richardson was taken prisoner at Gettysburg and sent to Libby Prison. With the approach of the Union Army toward Richmond, he and most of the prisoners were sent to other prisons deeper in the heart of the Confederacy, and ended up in South Carolina and Macon, Georgia, before being paroled in December 1864. After the war he returned home and married Mary Garside in October 1866.

The Iron Brigade, officially known as the 1st Brigade, 1st Division, 1st Army Corps, was formed in October 1861, from the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin, the 19th Indiana, and later joined by the 24th Michigan. The brigade was comprised of tall, tough and stubborn Midwestern farm boys noted for their ferocity in battle and not yielding. Known as Giants in Tall Black Hats for their wearing of the 1858 Hardee Hat, the unit were famous on both sides of the line. The Iron Brigade distinguished itself at the Battles of Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and at Chancellorsville. They received their name from General George McClellan who said “they must be made of iron” at the Battle of South Mountain.

Richardson was among those who didn’t march out. After being taken prisoner, he was sent to Libby. Originally a tobacco factory and warehouse, the 3-story building was ill suited to serve as a prison. The South was not prepared for the large number of Union prisoners being taken and both living conditions and the food were atrocious. By the time Richardson arrived, only officers were housed in the building. Approximately 1,000 men were housed on the top two floors with 100 men per cell. Add in that there was no glass in the windows, only bars, the elements took its toll on the already starved soldiers. Just two months prior to Richardson’s letter, 109 men escaped through a tunnel they dug with 59 making it to freedom, the largest such escape of the war.

Harland Richardson letter, April 24, 1864

All this brings me to the letter’s significance. The Confederates, realizing the prisoners were starving but had rations to barely feed their own troops, allowed the U.S. War Department to send food to the troops. I presume Richardson was writing to Mr. Reilly for food was in relation to this agreement. From the letter you can see what and how much was needed to sustain his group—such as 30 pounds of ham, 30 pounds of beans, along with rice, flour, lard, coffee, tea, cheese and chewing tobacco. Also stating that he is asking “once more” implies this was not his first request. Since Richardson was apparently also with Supplies with the 19th, it was logical he would be the one charged with making the request.

So, with the right letter content and some historical research one can learn a lot about a little-known aspect of a topic.