Plan your visit

“Bound for the Admiralty Island”

From The Hoosier Genealogist: Connections, Fall/Winter 2017. To receive Connections twice a year, join IHS and enjoy this and other member benefits. Back issues of Connections are available through the Basile History Market. Photo courtesy of Randy Mills.

Recovering and Reconstructing the Lost Story of My Father’s World War II Adventures

“I am so homesick for Horse Creek.”

In Part I of this series about my father, Keith Ladonne Mills (1924–1978), I told the story of my father’s boyhood, lived in the shelter of a rather isolated rural community called Horse Creek and in the midst of a large extended family. During those early years, he experienced a number of defining experiences: an influential relationship with a family physician named Doc Andy Hall, a bout of severe polio, and a relationship with Mary Frances Coffee, a girl he met in high school and began dating. The latter relationship grew complicated and took up much of his energy and time, but the United States’ entry into World War II pushed to the side those worries and any other personal problems my father may have had.

Ineligible for the draft in 1943, my father underwent an operation and subsequently entered the navy. Family tradition says he did so to escape Mary Frances. My examination of old family documents soon challenged this tradition and cast my father in a new light.

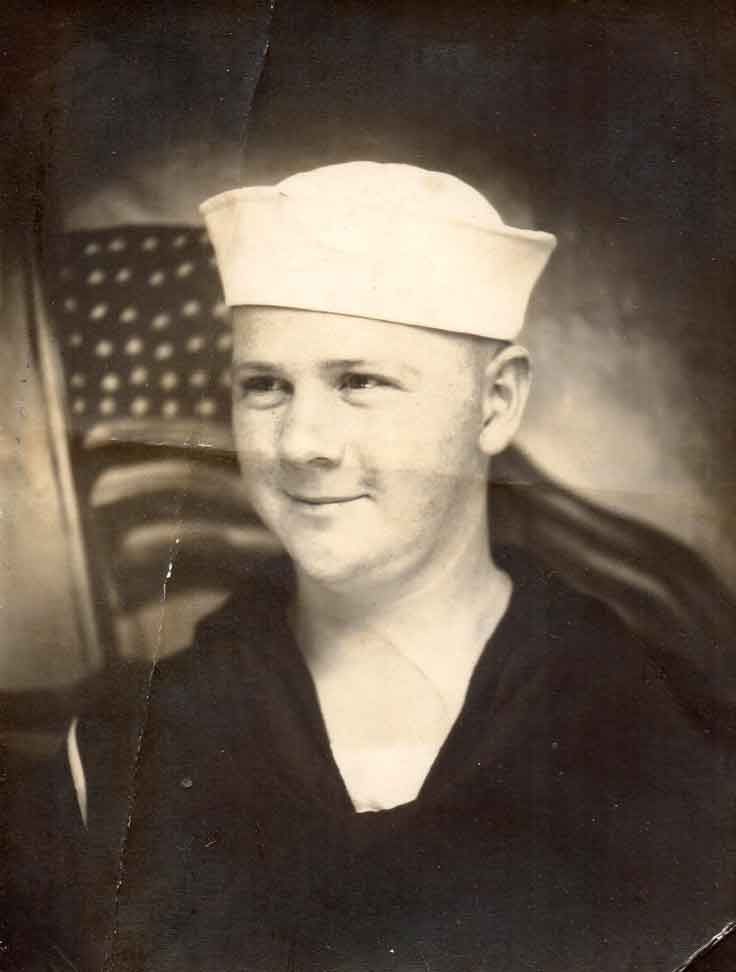

The first photo my father sent home from basic training to his parents and Mary Frances was of him in his navy uniform, his hair cut above his ears, the American flag waving in the background. He looks happy and proud, a sign perhaps that he had very much wanted to follow his friends into the service during the nation’s patriotic mobilization to war.

During my father’s time in the service, Mary Frances, who would become his wife, lovingly placed a number of important items—notes, telegrams, draft registration cards, military base newspapers, photos, and letters—in two huge brown scrapbooks. When the scrapbooks came to me, they were so stuffed as to be fat. The most essential items in the scrapbooks were the two dozen letters, telegrams, and postcards, sent mostly from my father to Mary Frances, although a few were to his parents. After reading the collection, I suspected there were many more such pieces of correspondence that disappeared over time. In one of my father’s letters to Mary Frances he mentions that he had already received fifty letters from her.(1) Still, the available correspondence and other new materials shed essential light on my father’s adventures during the war and reveal several heretofore unknown qualities that he possessed as a young man. Weaving his story together with this material and other sources has been one of the most satisfying experiences in my life.

His correspondence reveals a surprising fact—my father almost became a marine. In his first short, tense note sent by telegram to his future wife, he wrote, “So far I am in the Marines but have slight hope of getting in the Navy.”(2) For whatever reason, his initial enlistment in the navy seems to have gone south when he arrived at the Great Lakes Naval Station in Chicago in early March 1944. It may have been during this time that he received what he called brief “Marine training.”(3) Had he stayed this course, he could have faced serving in an arm of the military that would be in savage fighting, reclaiming scores of tiny remote islands from a fanatic enemy and taking heavy battle casualties. But the biggest surprise from the telegram is not about the branch of military in which my father served but about his relationship with his girlfriend. The telegram clearly indicates that he was not escaping Mary Frances.

When my father left the Great Lakes Naval Station, he was still unsure whether he would be a sailor or a marine. He also did not know his destination for basic training. In a hastily written postcard penned to his family on April 5, 1944, he wrote, “Dear Kermit and all: Am on my way. Don’t know where. I will be in the western part of the country, may be a marine. Write when I am stationed. Keith.”(4) He soon discovered his destination was the United States Naval Training Center in Farragut, Idaho.

In the set of letters I came to possess, my father’s first piece of correspondence arrived from Idaho, written to Mary Frances, a little over a month into his training there. This letter is not just shocking in terms of the family tradition of conflict between my father and his future wife; it simply blows the tradition all to pieces. My father wrote:

May 19, 44

Friday night.

Dearest Mary,

Well I received one letter from you today. I never got any tonight. Honey we will have to get married through the week as I won’t have but one Sunday at home I am afraid and it will be time to come back here the following Mon. Yes I am sure we will be happy when we are married and anything could beat the food here, ha. Tomorrow we get our railroad tickets home. Mine cost $50.

Honey about going to [navy training] school I am pretty sure, but anything can happen here in this hole. . . . I will talk to you about it when I get home. I have already taken short marine training and love their type of training compared to this rolling [folding] clothes [properly] etc.

Honey, in about 9 days from today I should be at home with you. We will get married and I will come back and when I get stationed I will send for you. That sounds swell. That will be the happiest moment of my life when I have my darling girl, my mate for life with me. My partner to fight for, to worry together, to enjoy life together and share the tremendous love we have for each other. Hon just keep dreamin’ and we will soon be married.

Another portion of the letter strongly suggests, even with all the talk about marriage, how unacquainted the young couple really was:

Hon, my mother has been sick, and that is the reason she has not written you. She wrote me and said she hadn’t heard from you either. My middle name is spelled Ladonne, honey. Well darling I will close for now. Next week darling I probably won’t have much time to write but I will try to deliver myself to you next Sat., or Sun., or Mon. night. We could be held over until the following Mon but don’t think so. Well, write darling and be patient as I have to be and do the Navy way.

XOXOXO, Lovers forever

Reading the letter left me stunned. I had never seen this side of my father before. Besides letters revealing that my father was a homesick and lovelorn young man, Mary Frances’s scrapbook contains an activity card that indicates that my father regularly attended and participated in the choir at the Farragut base, another surprise to me. The scrapbooks show that my father, so different from the man I would know, was once a nineteen-year-old with the powerful hopes and dreams that are so typical of youth.

A time gap of some extent exists in the letters, and the next one I have was written six weeks later. My father was then taking advanced training at Iowa State University, studying to be a navy electrician’s mate. There is no mention of the marines or marriage in this letter. Perhaps the missing references to marriage explain the missing letters, as they may have contained some very intense and personal dialogue over the issue of marriage that Mary Frances and my father did not wish others to see. The letters that remain in the collection, however, do portray the writing of a love-struck sailor:

June 23rd 44

Friday night.

My Darling Mary,

I am writing you another letter today because I do want you to know that I love you with all my heart. It is 10 after 4 now and they pick up the mail at 4:30 so I must hurry with this. I tried to call you honey but there was no answer so supposed you and Ruby [Mary’s mother] were up town. I will try to call again very soon maybe next week. . . . Well darling, I will get this in the mail because I want it to go out so you will know I love you so much and want you. As I sit here I hear the birds and tractors and I am so homesick for Horse Creek. I could come home in a day but I am in the Navy now. Well, write everyday Honey.

Yours forever, Keith L. Mills

N.T.S. Iowa State College

Ames, Iowa

A week later my father lamented about his feelings of homesickness, and his letter reveals a sense of incredible restlessness:

June 30, 44

Dearest Mary,

Well, tonight finds me very tired. I have been studying and marching like the dickens. I never got any mail today from you and tonight I am very sad, although I do get your pictures of those of you and me and that larger picture of you out and look at them all the time. I love you darling and I am so fed up marching that I am sick at heart. I wish so bad to be home. Honey, this [the college] is a swell place but honestly I would rather go to sea and then I could say I had a part in this war. Write your version on this. I don’t want to be hasty but I can’t stand 4 or 5 months being cooped up in rooms and being restricted in a 2 acre pen. It is like a penitentiary or worse I would put it. Yes, I will be happy when this thing is over. I am pitching softball for the team here and today I gave up 5 hits and got 2 three bag[g]ers [triple hits] for myself. Another boy from Miami Florida is catching and we have quite a team. Well darling I love you so much and want you. Mary if ever I thought you were untrue to me I would die of misery.

My father’s comments about playing softball for a navy team is of great interest to me, as I never had any clear sense of his sports abilities as a young man. Another letter from him to Mary Frances lamented a situation besides homesickness: “I don’t like to study very good. I got behind while I was sick and it is so hard to catch up. I will be a mental wreck when I get through here. . . . I hope you don’t mind my being disgusted with this but everyone here is. Most boys like action and it is very monotonous here baby.”(5) My father’s concerns over his schoolwork had merit. Mary Frances pasted a number of my father’s electrician class worksheets in her scrapbooks. The scores marked on these sheets by instructors were average at best, with one paper being marked in big, bold red ink and underlined: “Wrong Method.” I suppose my father was at last discovering that the real world does not indulge people.

“I will fight my heart out.”

Other letters that soon followed indicate a new topic of concern: my father preparing Mary Frances, and, perhaps himself, for his going to war. Three letters written while he was finishing his advanced training at Iowa State are particularly poignant. My father’s tone shifted as he considered the war and his likelihood of going to sea:

July 11, 44

My Darling Mary,

I received two letters from you today honey. I wished that you could spend 24 hrs a day writing to me honey, but of course you must sleep and eat and have some pastime. Tonight my heart is heavy. Mary I can hardly bear the thought of having to remain away from you much longer. It hurts my heart so that I get sick. But honey you may not believe what I have to say but here it is—people are too optimistic. . . . it isn’t about over yet. We have a long ways to go and my chief told me that by Christmas we would or most of us would be on the sea. I figure I will hit the invasion of the Philip[p]ines which according to the opinion of our general staff will be under¬way about then. Darling I am afraid that it will be quite a spell before we can be together forever. My darling you know if this does happen you know that I will fight my heart out so as to return to [you].

On July 13, 1944, my father wrote Mary Frances, trying to calm her worries about his faithfulness if he went overseas and addressing the same issue from her end:

My darling sweet, please know that I love you with all of my heart sweetest and want you so bad really darling. . . . Mary my love is so great for you. Really my darling you would never have to worry one minute about me for I will be true to you forever darling, oh Mary I wish I were with you to stay to love you up and hold you and kiss you. Honestly sweet it won’t be long until your papa will be out there fightin. It doesn’t seem possible but it is. Wait for me always darling and be true. No one could love you any more than I do baby. . . .

Yours forever

XOXOXOXO

Mary Frances’s response must have been intense, as my father’s next letter of July 17 continued to dwell on the pos¬sibility of his going to war overseas, but with a new twist:

My Dear Mary,

I received two letters from you today and will answer your questions. Yes I believe this war will last probably two more years. . . . They are going to close this school in the near future and I might possibly be transferred to New Jersey. The last Diesel company leaves in August. Chief Gregory said this afternoon after classes that the Navy is closing all of its college and university schools.

Another piece of good news was the possibility Mary Frances would finally be able to visit with my father at the Iowa State naval training facility, along with my father’s parents. Rising tension between Mary Frances and my father’s parents seems apparent, however, as she kept placing pressure on them to hurry as soon as possible to Ames. In the July 17 letter my father spoke of this situation, writing, “Now honey, don’t be so impatient, I am afraid that they won’t come for awhile as my mother said in today’s letter that she wasn’t feeling very good now and that they wanted to wait till they got tires for the car and a C book [a gas ration stamp book based on need], so be patient my darling and they will come soon I hope and you will come with them.”

This misunderstanding between Mary Frances and my grandparents may have persisted, as suggested in a letter written from my father to his parents later in the war, one informing them how much he cared for his gal. “Well here I [am] again today for the second time and to say I am so very, very happy for I got five big long, fat letters from my darling Mary today. Sure lifted a load off of my shoulders.” He continued, “She wants to know why you don’t write or come to see her and you wonder the opposite, so you had better get together, ha ha.”(6)

Expensive telephone calls were another issue between my father and Mary Frances while he was stationed in Ames. “Mary about calling again, write me and let me know if you wish me to, but if I did, ten dollars is all I can send [for calls] until Aug 5th. . . . I have to pay my laundry. I am really having to scrap like hell.”(7) In another letter my father repeated his concerns. “Honey about calling, remember pop hasn’t got much money, so please darling don’t expect them so often. I couldn’t possibly send over $15 and then it would be awfully hard to scrape up.” He signed off on the letter, “I love you my darling with all my heart please believe me.”(8)

Although the correspondence does not mention an Iowa State naval training visit, a photo found in Mary Frances’s scrapbook is a witness to the event. It may also be telling about this juncture of the young couple’s relationship. It shows my father and Mary Frances in front of the main administration building on the Iowa State campus, standing in front of a car. My father is frowning and has his head turned to the side, away from Mary Frances and the camera, while she looks at the camera with an unhappy expression.

Interestingly, my father’s relationship with his future mother-in-law, if the letters give any indication, seems very healthy. He wrote her several letters, all praising Mary Frances. In one correspondence, he cheerfully wrote, “Here comes a few lines this evening. I am hoping you are all O.K. I am as usual, just living for that day when I can go home to my baby. . . . Take good care of her for me Ma. Enclosed in this letter is $50, with which to buy my honey her coat for Christmas. . . . Let me know when you get this, and when you buy the coat and what kind etc. . . . Give baby a big kiss for me. . . . All my love always. Your Future Son-in-Law, Keith L. Mills.”(9)

In late October 1944, my father, along with other sailors who had trained at Iowa State, boarded a smoke-belching train for the West Coast. While staying at a servicemen’s center in Omaha, he wrote Mary Frances a quick letter:

Oct. 20, 44

Friday night

Dearest Sweetheart,

I am lonesome for my baby tonight and get more so as I move farther away from home. I have met about 20 of the other boys so I am not by myself so I won’t have to be punished alone, ha. I am in the USO writing to you, it is sure a swell place. Omaha is a pretty city and rather large. I love you my dar[ling]. You surely know that. . . . hope you love me as much and will be true to me and wait for me. . . . I wish I were home to stay. Maybe it won’t be too long. Well my dear one I will close for this time maybe I will get to write another letter to you on the way. Write every day.

Yours forever.

At the time of this letter’s writing, news of the American invasion of the Philippines had just broken. General MacArthur had indeed kept his promise to return. The invasion was in line with my father’s earlier prediction, save for it taking place two months before Christmas. The knowledge of the event likely heightened his concerns about going overseas. The next evening, a Saturday, he wrote from Denver, telling Mary Frances he still had “a long way to go” and that he would probably “get to California sometime Monday.” He ended the letter by saying “I love you Mary,” asking her to “please be true” and adding, “I always will.”(10)

A week later my father watched from the deck of the USS Exchange, a banana boat refitted for military use, as it sailed under the San Francisco Golden Gate Bridge and headed west to sea, the mainland fading away into the hazy distance.(11) It must have been both a scary and an exciting time for an inexperienced young man from a backward place called Horse Creek.

“I am writing this at sea”

What I know about my father’s journey to the South Pacific and to Manus Island comes from some unique materials in Mary Frances’s scrapbooks and from my search for other contextual materials. Regarding the latter, Peter Schrijvers wrote an insightful book that offers important context for my father’s experiences as he traveled west to war. Schrijvers notes that most servicemen heading for the Pacific War theater were “reluctant soldiers, thrust into a volatile odyssey by forces beyond their control.” Once on the West Coast, many servicemen laid eyes on the Pacific Ocean for the first time, a view that Schrijvers points out, “presented itself as a frontier of unfathomable proportions to most American soldiers. . . . Many a GI from the numerous landlocked states had never laid eyes on any of the seas bordering the US.”(12) Other exotic scenes awaited my father, scenes far beyond his Horse Creek-bound imagination.

Schrijvers relates another interesting aspect of many ser¬vicemen’s westward voyage, the practice of an ancient sailors’ ritual when crossing the equator. An elaborate and intense event of initiation turned novice “pollywogs” into seaworthy “shellbacks.” The mythical figures King Neptune and Davy Jones were always present at the exotic ceremony in the form of role-playing sailors, who also dressed as other archetypical ocean characters. Many servicemen remembered the ritual as one of the more unique experiences of their service and highly valued the elaborate certificate they received for being involved in the rite. Schrijvers notes that “sailing across the equator into that unknown southern part of the world and its mysterious ocean remained an important rite of passage, a test of stamina made worse by the prospect of battle.”(13)

My father took part in this ancient ceremony, which included some hazing and typically ended with the shellback candidates climbing up on a platform from which they were then pushed into large tanks filled with salt water.(14) Among the most interesting artifacts in Mary Frances’s scrapbook is the ornate certificate, on parchment-like paper—the Ancient Order of the Deep—declaring my father’s promotion from pollywog to “trusty shellback.” The document is dated November 17, 1944. My father also made mention of the initiation in a brief note on a half sheet of paper, also tucked away in one of the scrapbooks. “I guess I have it made. I am now a shellback.” Another short note indicated he also knew his destination at this juncture: “I am writing this at sea, bound for the Admiralty Islands.”

The bits of information gained from my father’s certificate for crossing the equator are significant. Manus, the largest island in the Admiralty Islands chain, is located just south of the equator; thus I know the approximate time of his landing there, likely about a week after the November 17 ceremony. This estimate is also supported by a short letter he sent his family in late November.

During the war, letters were typically censored whenever they gave too much detailed information about location, troop movement, or any event that could lead to heavy American casualties. This may be why my father wrote in generalities about a horrible event that occurred a couple of weeks before his arrival at Seeadler Harbor, the huge U.S. Navy base on Manus Island. The tragedy was apparently still the topic of sad conversations when he arrived.(15) On November 10, 1944, the USS Mount Hood, a large vessel holding more than four thousand tons of ammunition for the ongoing Philippines invasion, exploded while at anchor in the middle of Seeadler Harbor. The cause of the explosion was never discovered. A navy commander remembered, “One minute she was a ship teeming with life, humming with activity. Seconds later, she was a vast black billowing bier which marked the spot where 350 Navy men perished without a trace.”(16) In his only mention of this disaster, my father stated: “I’m really down today. In this war death can take hundreds of men in a split second even when there is no fighting going on. Life isn’t very fair I guess.”(17)

The naval base at Seeadler Harbor, located on the northeast side of Manus Island, was one of the largest bases of the war and served as a staging area for the invasions of New Guinea and the Philippines. Interestingly, the scrapbooks contain only this one letter from the time of my father’s arrival there. The letter gave no clue as to what he saw or thought when he first glimpsed the busy harbor. However, an account written by Colonel Thomas B. Protzman, commanding officer and a naval doctor on the hospital ship USS Hope, gives an idea of the fantastic site my father must have seen when the USS Exchange sailed into the harbor in late November: “From a panoramic view Seeadler harbor is a beauty; it’s semi-circu¬lar with small palms covering coral reefs scattered here and there; the harbor itself is 6 miles wide and 120 feet deep. This is my first close view of a south sea island and it looks like the jungle is coming right down to the sea with some even growing into the water.”(18)

Beyond the huge harbor, my father would have also seen a portion of the lush, jungle-covered island. Protzman remarked that Manus Island had “fine roads” that the navy “had built in just a few months, converting the island into a well developed and huge base for troops, supplies, repair facilities, and an excellent harbor.”(19) At the south end of the island rose a 2,356-foot mountain that had once been an active volcano. It is difficult to say what my father’s feelings were about his arrival on Manus Island, for in the earliest photos that he sent home from there, he is always alone, with a guarded expression.

My father would spend the lion’s share of his time in military service working in the military transportation department at the Seeadler Harbor base. In his motor pool assignments, he would soon meet and interact with a people who, on first glance, seemed more exotic than anything he could have imagined while living in his Horse Creek community. These interactions, along with other events in his life while he served on Manus Island, would come to greatly define my father as a man, creating in him an even deeper love for his rural community and for his future bride. Fate, however, would be kinder to my father while he served overseas than upon his return.

To be continued in the Spring/Summer 2018 issue of THG: Connections.

Notes

1. Letter from Keith Mills to Mary Frances Coffee, January 2, 1945.

2. Telegram from Keith Mills to Mary Frances Coffee, March 1, 1944.

3. Letter from Keith Mills to Mary Frances Coffee, May 19, 1944.

4. Postcard from Keith Mills to “Kermit and all,” April 5, 1944.

5. Letter from Keith Mills to Mary Frances Coffee, July 13, 1944.

6. Letter from Keith Mills to “Dearest Pop, Mom, and Brother,” May 29, 1945.

7. Letter from Keith Mills to Mary Frances Coffee, July 17, 1944.

8. Letter from Keith Mills to Mary Frances Coffee, July 16, 1944.

9. Letter from Keith Mills to Ruby Coffee, October 4, 1945.

10. Postcard from Keith Mills to Mary Frances Coffee, October [21?] 1944.

11. The knowledge of the name of the ship on which my father sailed overseas, the USS Exchange, came from the certificate he received in his equatorial crossing ceremony. Among the photos in Mary Frances’s two scrapbooks are a number of shots of the Golden Gate Bridge.

12. Peter Schrijvers, The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in the Pacific during World War II (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 3, 5.

13. Ibid., 7.

14. Ibid.

15. See Bill Adler, ed., World War II Letters: A Glimpse into the Heart of the Second World War through the Eyes of Those Who Were Fighting It (New York: Saint Martin’s Griffin, 2003), for a discussion of the heavy censoring of the letters of servicemen and women.

16. Chester Gile, “The Mount Hood Explosion: The Official Investiga¬tion and Eyewitness Accounts by Survivors,” Proceedings (United States Naval Institute, February 1963), on the OoCities.org website, http://www.oocities.org/.

17. Letter from Keith Mills to “Dear Family,” November 22, 1944.

18. Testimony of Thomas B. Protzman, October 17, 1944, WWII US Medical Research Centre, https://www.med-dept.com/.

19. Ibid.

Randy Mills is a professor of history at Oakland City University in Oakland City, Indiana. He is the author of several books, including Jonathan Jennings, Indiana’s First Governor, published by the Indiana Historical Society Press; and Troubled Hero: A Medal of Honor, Vietnam, and the War at Home, published by Indiana University Press. He is also the editor in charge of the Journal for the Liberal Arts and Sciences published by Oakland City University and available for free, online at http://www.oak.edu/academics/school-arts-sciences-jlas.php.