Plan your visit

October 14, 1851 – 174 Years Ago: Hoosier Women’s Fight Began

October 18, 2024

Americans began to call for women’s suffrage as early as 1850, 70 years before the 19th Amendment granted white women the right to vote, and 115 years before women of color won the right to vote with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Do you know when Hoosiers began their participation in the women’s suffragist movement?

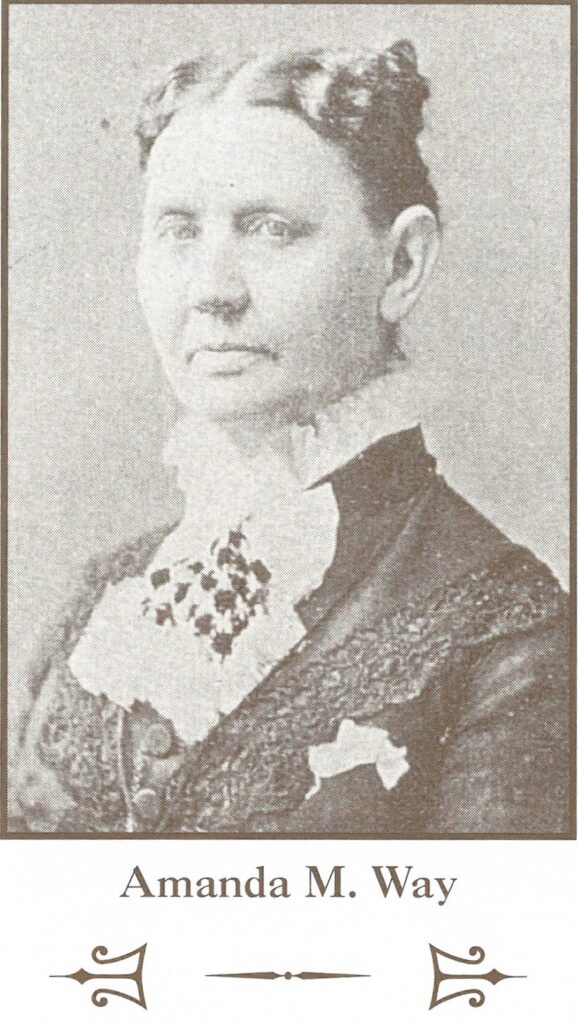

the Greensboro anti-slavery meeting of January 1851, one woman introduced the first resolution in Indiana regarding women’s suffrage. Amanda M. Way, born in Randolph County, Indiana, in July 1828, called attention to the way women of Indiana were being mistreated by laws of the state and country. Following this call to action, the first Women’s Rights Convention was held in Dublin, Indiana, on October 14 and 15, 1851.

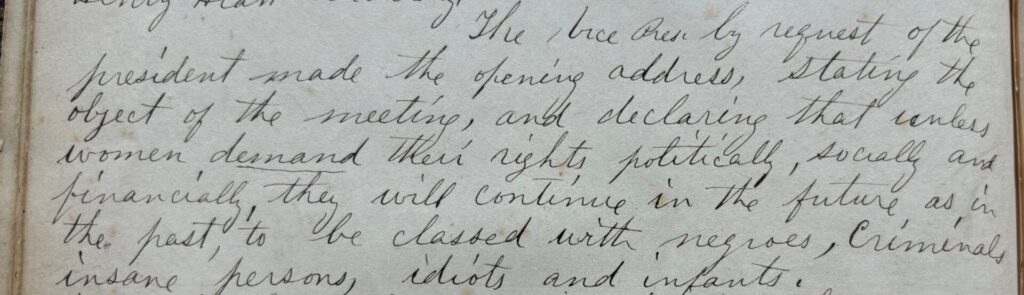

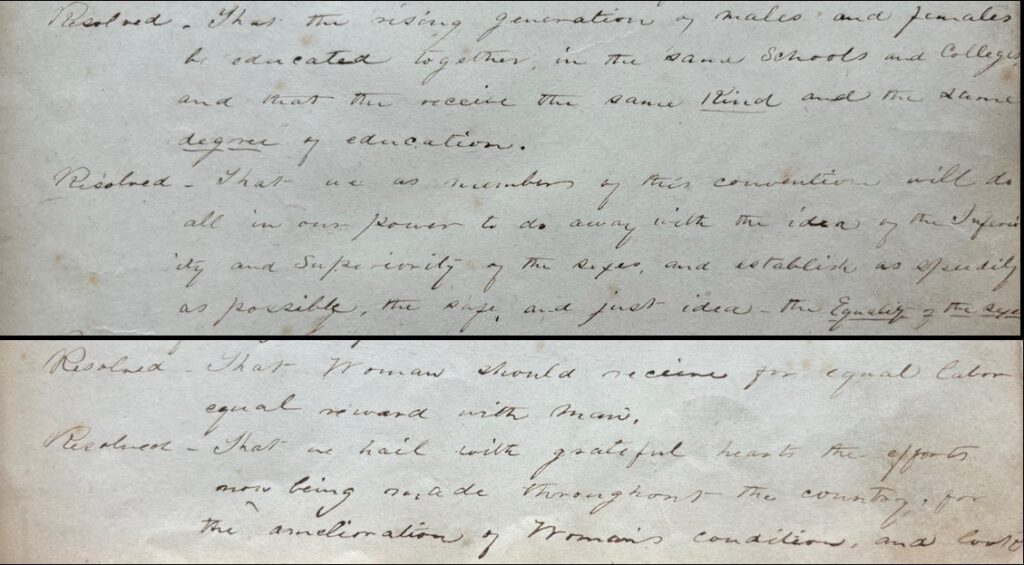

The first elected officers of the Indiana Women’s Rights Convention were Hannah Hiatt, president; Amanda M. Way, vice-president; and Henry Hiatt, secretary. Henry C. Wright was a guest lecturer at this meeting, well-known throughout the States as an abolitionist and feminist. By 1852, the Indiana Women’s Rights Convention adopted a constitution and drafted multiple resolutions to lobby for. A few included the right for women to vote, equal opportunities for education, the dissolution of the idea of superiority and inferiority between sexes, and equal pay for equal labor.

Indiana Women: 150 Years of Raised Voices: Sesquicentennial of Indiana’s First Woman’s Rights Convention, Indiana Historical Society, Pam.Q HQ 1236.5 .I6 I6 2001

Excerpt from minutes of the first meeting, Women’s Suffrage Assoc of Ind., Indiana Historical Society, BV2577

Women’s Suffrage Assoc of Ind., Indiana Historical Society, BV2577

The Indiana Women’s Rights Convention would meet annually until events of the Civil War dictated they postpone meetings, instead putting all their efforts into supporting the war and their families. Amanda M. Way would be the one to pull everyone together again in 1869, renaming the organization the Indiana Woman’s Suffrage Association as a chapter of the National Woman Suffrage Association.

They continued growing their membership and organizing committees to lobby for amendment of the Indiana Constitution but were constantly facing roadblocks; in 1881, the state legislature finally approved an amendment granting Hoosier women the right to vote, but this was withdrawn at the 1883 meeting, where it was found that the law was “mysteriously” not recorded in official records.

(*Read with sarcasm*) I am now convinced this is why notetaking and record-keeping became socialized as “women’s work.” Women weren’t going to let that happen again.

Following that, the suffragists became more organized and persistent. More petitions, more speeches at open session, more publications in local newspapers, more councils and committees to establish women in the state house (the Women’s Franchise League, the Legislative Council, the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society). World War I would slow things once more as suffragists dedicated part of their energy to support the country, but they continued to fight for the cause.

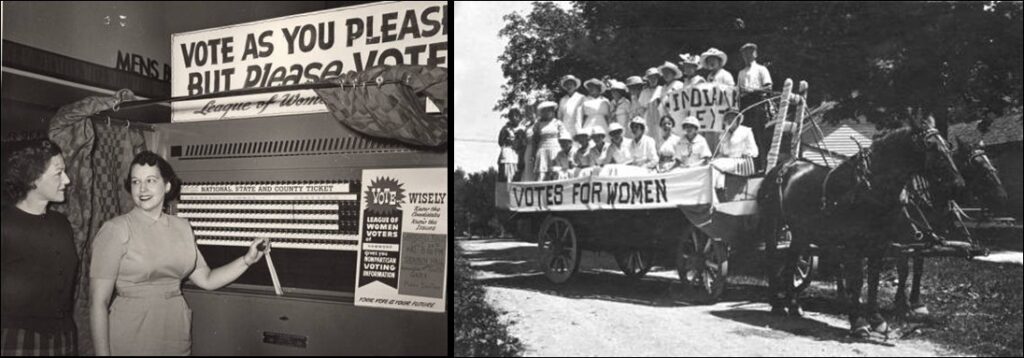

In 1917, Hoosier suffragists finally had a breakthrough. The Indiana General Assembly passed three laws benefitting women’s suffrage, including the right to vote for presidential electors, state offices, and municipal elections. That year, women flocked to register to vote. By the end of the summer, 80% of registered voters in Porter County, Indiana, were women (Morgan, 2019).

LEFT: Voting Booth, League of Women Voters, Indiana Historical Society, M0612. RIGHT: Postcard, Suffragists in Hebron, Indiana, Indiana Historical Society, P0408.

The Indiana Supreme Court would strip these rights and find the newly passed laws unconstitutional before the end of October, but that only fueled the suffragist motivation to participate in Carrie Chapman Catt and the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s “Winning Plan.”

And win they did! Indiana became the twenty-sixth state to ratify the 19th Amendment following U.S. Congress’ approval, on January 16, 1920. White women were granted the right to vote. On May 26, 1965, forty-five years later, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 granted English-speaking women of color the right to vote, and an extension in 1975 would grant non-English-speaking women of color the right to vote.

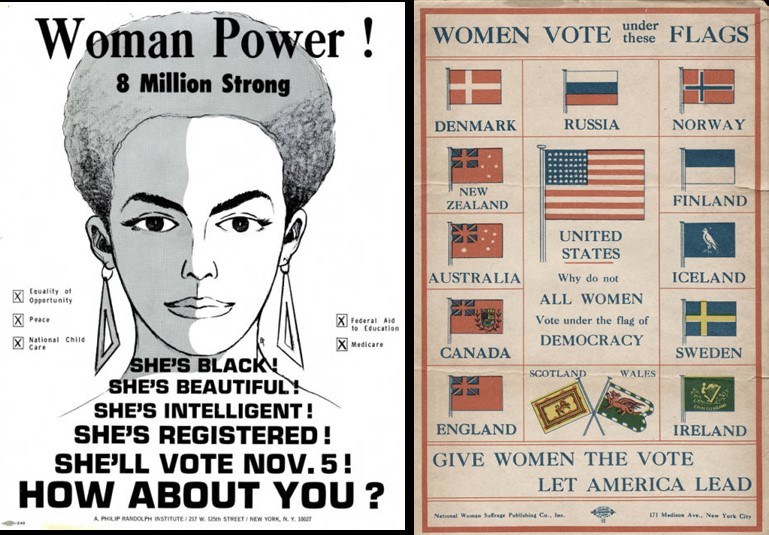

LEFT: Woman Power!, Indiana Historical Society, M1250. RIGHT: Women Vote Under These Flags, Indiana Historical Society, M0612.

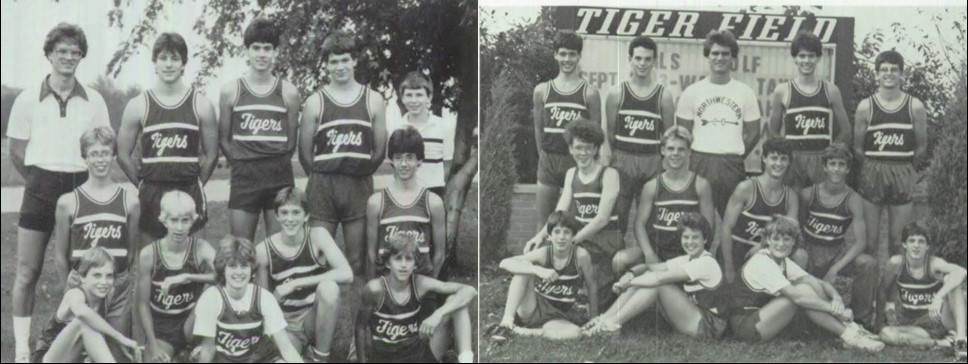

Take a moment to reflect on how far women’s suffrage and rights movements have come. Personally, without Amanda M. Way speaking up in 1851, the work of the Indiana Women’s Rights Convention/ Women’s Suffrage Association of Indiana, the National Woman Suffrage Association, the 19th Amendment, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and Title IX, I would not have the honor of being the daughter of the first few women to run cross country for our alma mater, Northwestern Jr-Sr High School. Amy Rubenalt has the honor of being the first in 1983, my mother (Monique French) and Natalie Griffey following in 1985.

LEFT: Amy Rubenalt is pictured center, first row, Northwestern High School PANORAMA 1985, Howard County Memory Project. RIGHT: Monique French & Natalie Griffey are sat back-to-back in first row, Northwestern High School PANORAMA 1987, Howard County Memory Project.

The history of women’s suffrage is full of setbacks and swimming against the current; I hope we persevere and continue onward, just as our ancestors did.