Purchase Tickets

Survivance and Continued Existence of Native Peoples in Indiana

November 21, 2022

Guest blog post

As we celebrate Native American Heritage month, which often focuses on the tragedy of the Federal policy on Indian Removal, in which hundreds of thousands of Native peoples were forcibly removed from their homes to lands unknown, we must also celebrate the survivance and continued existence of Native peoples in Indiana following the passage of the Indian Removal Act.

In October 1846, the Miami Nation, the last tribal nation in Indiana, was forcibly removed by the United States military to a new reservation west of the Mississippi River, in present-day eastern Kansas. However, not all Myaamia (Miami Indian) people were removed to the Miami Reservation.

As the Miami Nation prepared for their forced removal, Myaamia leaders had secured the exemption of four Myaamia bands (the Richardville, Godfroy, Meshingomesia, and Slocum/Bundy bands), numbering approximately 150 people. The Richardville Band was exempted in the Treaty of 1838 and the Godfroy and Meshingomesia bands were exempted in the subsequent Treaty of 1840, which authorized Myaamia removal. The Slocum/Bundy Band was exempt five years later, in 1845, through an Act of Congress.

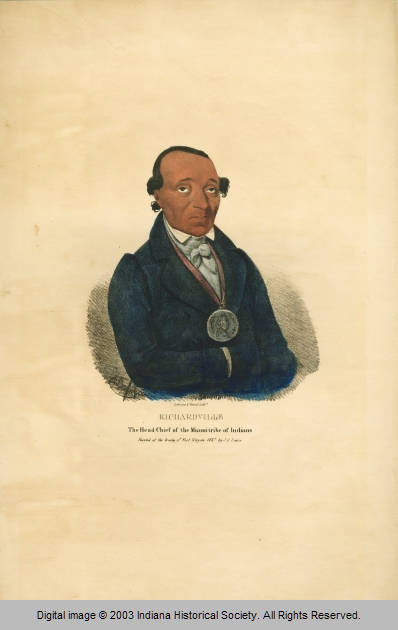

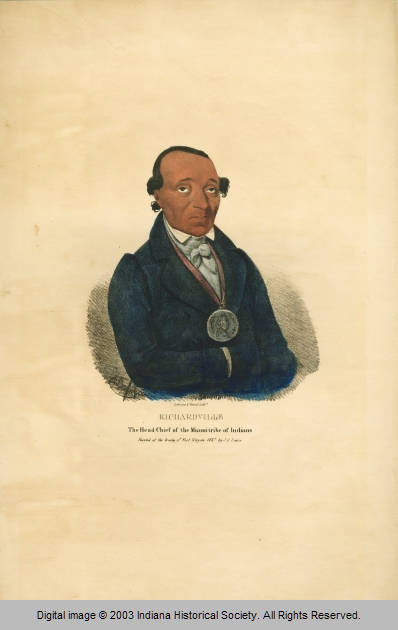

1 Pinšiwa (Jean Baptiste Richardville), Maawikima (Principal Chief) of the Miami Nation

In the four years after removal roughly 109 additional Myaamia people, most of whom had walked back from the Miami Reservation, received further exemptions from Congress. These 259 Myaamia people and their descendants became known as Indiana Myaamiaki or Indiana Miamies.

In order to secure the exemption of the vast majority of Indiana Myaamiaki through Congressional legislation, the Miami Nation relied upon legal representatives who could lobby for them in Congress and with the Office of Indian Affairs. At the forefront of their legal defense was Alphonso Albert (A.A.) Cole, an American who had only received his legal degree a few years earlier in 1853. Cole’s parents had emigrated to the newly created Miami County, Indiana in 1834, as part of a wave of migration into Myaamia lands that had been recently ceded to the United States in 1826 by the Miami Nation and several Potawatomi communities in northern Indiana and southern Michigan. Cole’s father, Albert Cole was elected as a judge in the Indiana District Court in 1840, and soon after A.A. followed his father’s legal path.

By January of 1845, A.A. Cole’s services had been retained by Mahkoonsihkwa (Frances Slocum), a Myaamia akimaahkwiaki (Miami female civil leader), who represented a village on the Nimacihsinwi Siipiiwi (Mississinewa River). Americans called the village “Deaf Man’s village” after her deceased husband Šiipaakana also known as Keekiiphšia (Deaf Man). Mahkoonsihkwa and Cole successfully argued that she and her village should be allowed to remain in Indiana following the Miami removal because her daughters, Oonsaahšinihkwa (Jane Slocum Godfroy Wapshing Bundy) and Kiihkinehkišiwa (Nancy Slocum Brouilette), had received a jointly-owned reservation in the Treaty of 1838, on which they could provide for their families after the Miami Nation was removed. Additionally, Mahkoonsihkwa pleaded that at the age of 73, she would not be able to survive the long and hard journey westward to which the United States had condemned her.

Mahkoonsihkwa (Frances Slocum)

In the aftermath of Myaamia removal, Cole continued to work for the Miami Nation as their attorney, successfully seeking further exemptions for the families of Misihkwa (Mazequah), Pinšiwa (Wildcat), Aloolaawa (Alola), Amehkoonsa (Seek), Waapimaankwa, Mihtekwahkia (Coesse), Amehkoonsihkwa (wife of Benjamin), Šowapinamwa (Antoine Revarre), Kinooseensa (Peter Langlois), and Maankoonsa (John Mongosa), among others who had walked back to their homelands from the Miami Reservation. Many of them, like Mahkoonsihkwa’s daughters, owned their own reservation lands through previous treaties and argued that they could sustain themselves on their privately owned lands. Today Cole’s papers, which include his important work with the Miami Nation, are held by the Indiana Historical Society.

Thanks to the important collaboration between the Miami Nation and A.A. Cole, almost half of Myaamia tribal citizens remained in their traditional homelands across Myaamionki (the Miami country), where many Myaamia people continue to reside to this day. Today Indiana Myaamiaki, the descendants of those 259 Myaamiaki, are enrolled in the federally recognized Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and the non-recognized Miami Nation of Indians of Indiana.