Plan your visit

From The Cataloger’s Desk: Return to Rare Book School, Part II

October 12, 2021

In my last blog post, Return to Rare Book School, Part I, I discussed the “Descriptive Bibliography: The Fundamentals” course I took from David Whitesell, Curator at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia. I also touched on the following elements of a basic bibliographical description: format, collational formula, and statement of signing. Using the Indiana Historical Society’s copy of An account of Monsieur de la Salle’s last expedition and discoveries in North America … as our “practice” book, we determined the format is octavo (8°), the collational formula is [A]2 B-R8, and the statement of signing is [$4(-P2,3) signed]. This time, we’ll focus our attention on the number of leaves and pagination statement.

A leaf is a piece of paper comprising one page on its front (recto) and another on its back (verso). If we wanted to take the long way of calculating the number of leaves in our book, we could simply count them. Fortunately, however, there’s a shorter way, which is based on the collational formula: [A]2 B-R8. As we can see, there are 2 leaves in gathering [A] and 8 leaves each in gatherings B through R. If we count, there are 17 letters from B to R, but do you remember what I said about the printer’s alphabet in my last blog post? It consists of 23 letters, excluding I or J, U or V, and W. In the case of our book, the letter J is excluded. This means there are 16 (not 17) letters from B to R. So let’s do the math: 2 + (16 x 8) = 2 + 128 = 130 leaves. Voilà!

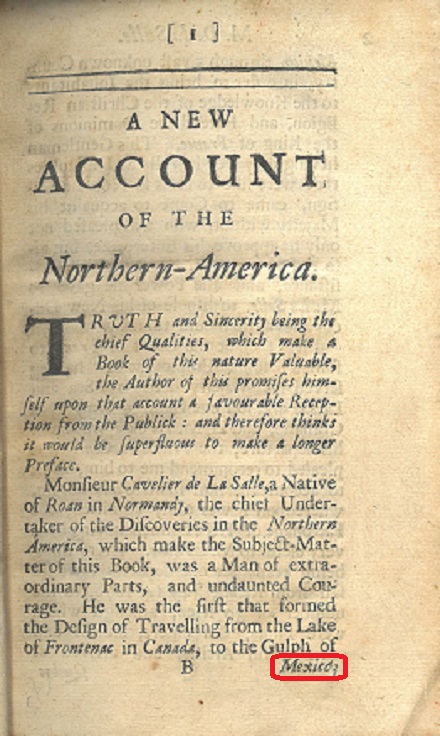

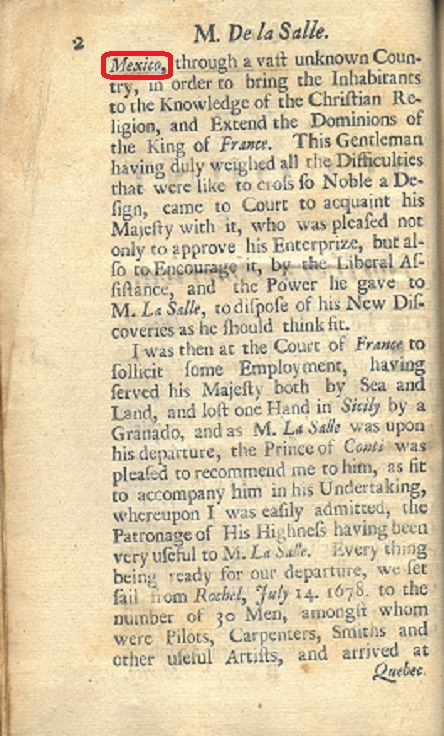

Recto of leaf B1. Notice the catchword at the bottom. This will be the first word on the following page.

Verso of leaf B1. Notice the first word at the top. This matches the catchword from the previous page.

Now that we have calculated the number of leaves in our book, the pagination statement should be easy, right? Wrong! We might be tempted to simply look at the last numbered page of our book, or to multiply the number of leaves by two. Determining the pagination statement, however, is much more involved. David explains that it should “include all leaves, including blanks, that were part of the letterpress sheets; follow the printer’s method of enumeration … infer page numbers when possible; [and] note any pagination errors.” This requires close examination of every single page of our book. In An account of Monsieur de la Salle’s last expedition and discoveries in North America …, the following information can be gleaned:

- There are 4 unnumbered pages at the beginning of the book.

- There are 2 separately numbered sections of the book.

- The first numbered section begins with 1 and ends with 211. It is followed by a single unnumbered page.

- The second numbered section begins with 7 and ends with 44. It is preceded by 6 unnumbered pages.

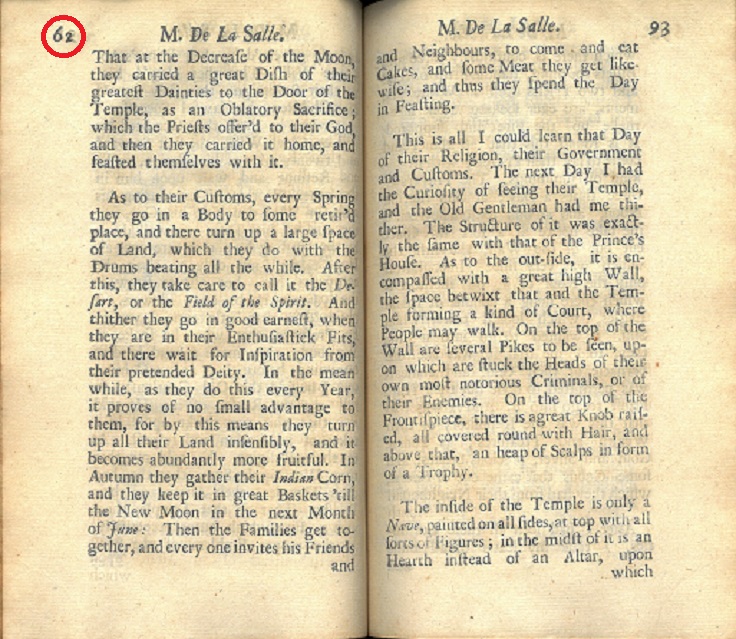

- Page 92 in the first section is misnumbered as 62.

- Page 143 in the first section is misnumbered as 145.

Before recording our pagination statement, we must take a few things into consideration. First, inferred page numbers and sequences should be placed in brackets. Second, if an inference can’t be made, we must give the total number of pages in the sequence in italics, within brackets. Third, individually numbered sections are separated with punctuation and prefixed superscripts. Finally, misnumberings should be noted. Bearing all of this in mind, we can confidently state our pagination statement is: pp. [4] 1-211 [212]; 2[1-6] 7-44 [misnumbering 92 as 62, 143 as 145]. In other words, [4] represents the 4 total unnumbered pages at the beginning of the book. The first numbered section, 1-211, is followed by a single unnumbered page, which we can infer is page [212]. The second numbered section, 7-44, is preceded by 6 unnumbered pages, which we can infer are pages [1-6]. The semi-colon separates the two numbered sections, and the prefixed 2 identifies the second section. Last, but not least, the misnumbered pages have been noted.

Page 92 misnumbered as 62.

If we combine all the elements of our basic bibliographical description for An account of Monsieur de la Salle’s last expedition and discoveries in North America …, we have the following: 8°: [A]2 B-R8 [$4(-P2,3) signed]; 130 leaves, pp. [4] 1-211 [212]; 2[1-6] 7-44 [misnumbering 92 as 62, 143 as 145]. At this point, you might be asking yourself, what is the purpose of all of this? As Philip Gaskell (1995) states, “Bibliography can help us to identify printed books and to describe them; to judge the relationship between variant texts and to assess their relative authority; and, where the text is defective, to guess at what the author meant us to read. Plainly it is a basic tool for editors, whose aim is to provide modern readers with accurate and comprehensible versions of what their authors wrote. But librarians, too, aim to hand on texts, by caring for the books in their keeping and making them available; and to do this effectively – to know what they have got – they too must use the techniques of bibliography” (p. [1]).

I hope you have enjoyed our descriptive bibliography “sessions,” although we’ve only covered the proverbial tip of the iceberg. There is so much more to discuss, but neither David’s class, nor this space, could ever provide enough time for that greater journey of discovery. Instead, the basics must suffice. If you would like to explore An account of Monsieur de la Salle’s last expedition and discoveries in North America … further, you are welcome to view the Indiana Historical Society’s copy in person. The record can be found here. You will notice, however, that there are differences in how information is recorded in the catalog, as opposed to our bibliographical description. There is also a digitized version of a copy held by the John Carter Brown Library, which is conveniently available through Internet Archive. Either way, take a look, and see if you agree with all our findings!

Sources:

Bowers, F. (1994). Principles of bibliographical description. Oak Knoll Press.

Carter, J., & Barker, N. (2004). ABC for book collectors (8th ed.). Oak Knoll Press.

Gaskell, P. (1995). A new introduction to bibliography. Oak Knoll Press.

Whitesell, D. (2021, August 2-6). G-10b Descriptive bibliography: The fundamentals [PowerPoint slides].