Plan your visit

Collections Corner: Iva Jordan – Women’s Suffrage and Ernie Pyle

August 24, 2021

Sometimes one encounters an individual who may not be quite front and center in an archival collection, but who may connect a researcher with other places and people across the historical landscape. Iva Jordan could qualify readily as one of those Hoosier personalities. Through her acquaintances, she was positioned within range of two of the subjects we celebrate this month: National Ernie Pyle Day (August 3) and Women’s Equality Day (August 27).

An Indiana Historical Society acquisition from an Illinois donor in late 2020 included, amongst the materials, a variety of letters and documents which helped establish Iva Jordan’s link to a friend who expressed her passions regarding women’s suffrage, and correspondence also directed a path toward subsequent research showing Miss Jordan’s close association with Ernie Pyle. Clearly, neither of the subjects related closely and yet Jordan provided the pivot toward both individuals and their writing.

The acquisition bears a tale worth telling, as the donor, who moved into an old Illinois house, found a huge trunk of documents and memorabilia in her attic. The home had once belonged to Frank Jordan, a nephew of Iva Jordan, who had apparently emptied the Jordan home in Indiana after the deaths of both Iva and her sister-in-law and housemate, Bertha Jordan, transporting many of the documentary contents back to Illinois. The letters IHS received were among the many paper treasures uncovered by the donor.

Sadly, we do not know a great deal about Iva Jordan, nor is there much found surviving that she had written, other than the resignation letter she had drafted when she retired from teaching. We have no known photographs and have learned what little we know about her through letters received and acquaintances made.

The Indiana State Normal School building welcomed the first freshmen class in 1870 before its completion in 1875. The original 18-year-old structure was destroyed by fire in 1888, and ‘Old Main’ (above) was immediately erected on its foundation. Indiana State University photo.

She grew up in west-central Indiana, near the small town of Dana close to the Illinois state line. Iva had a very rural upbringing from her farming parents, Isaac and Margaret Jordan, and appears to have been an astute learner. She later attended Indiana State Normal School, subsequently Indiana State University, to fulfill her aspiration to become an educator. Once acquiring a secure position, she taught in and around her native Vermillion County area for the latter 25 years of her career, retiring in 1927. Among her more notable students was one future journalist of international acclaim, who may well have found some seed of inspiration for his career path through the example of instructors like Miss Jordan.

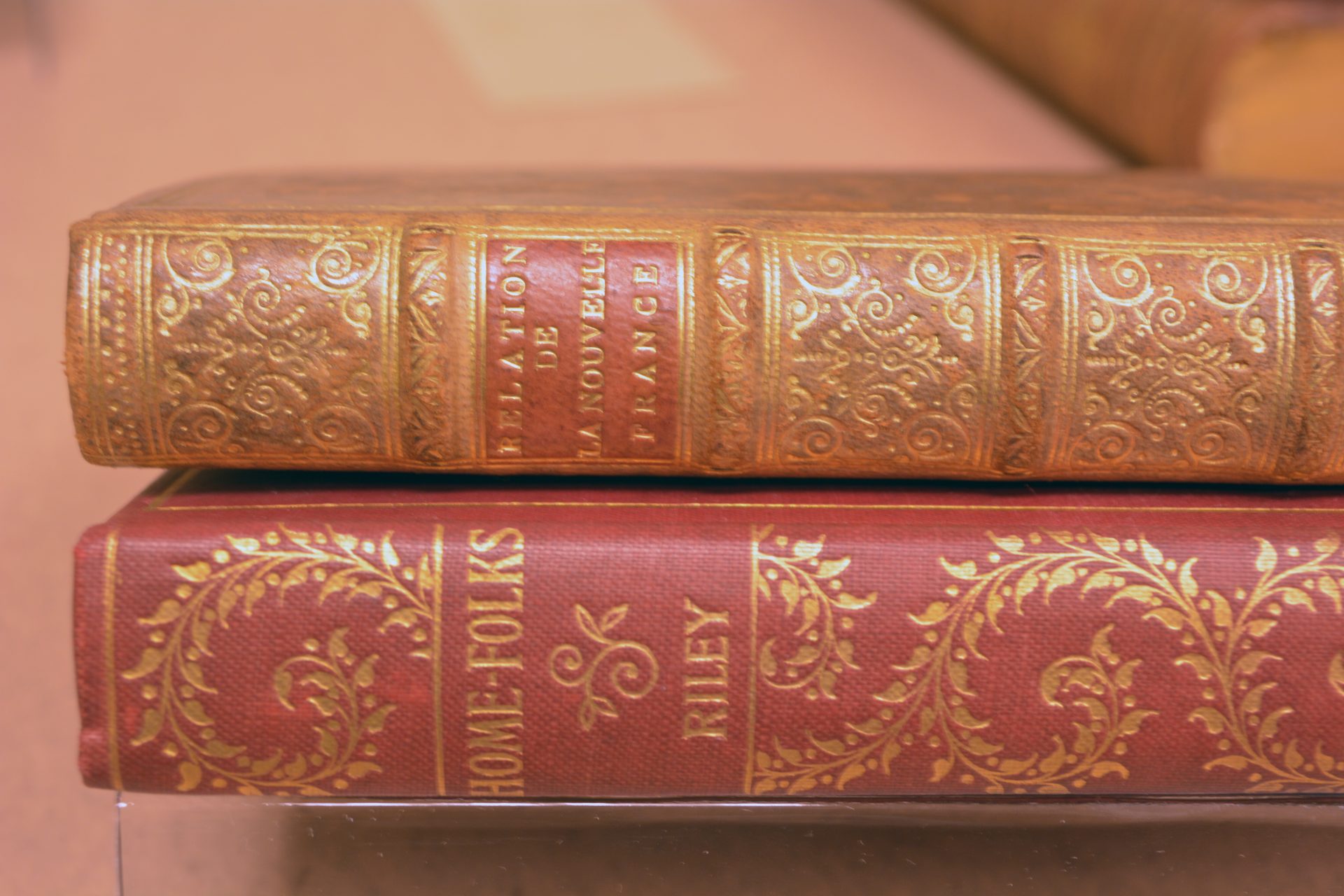

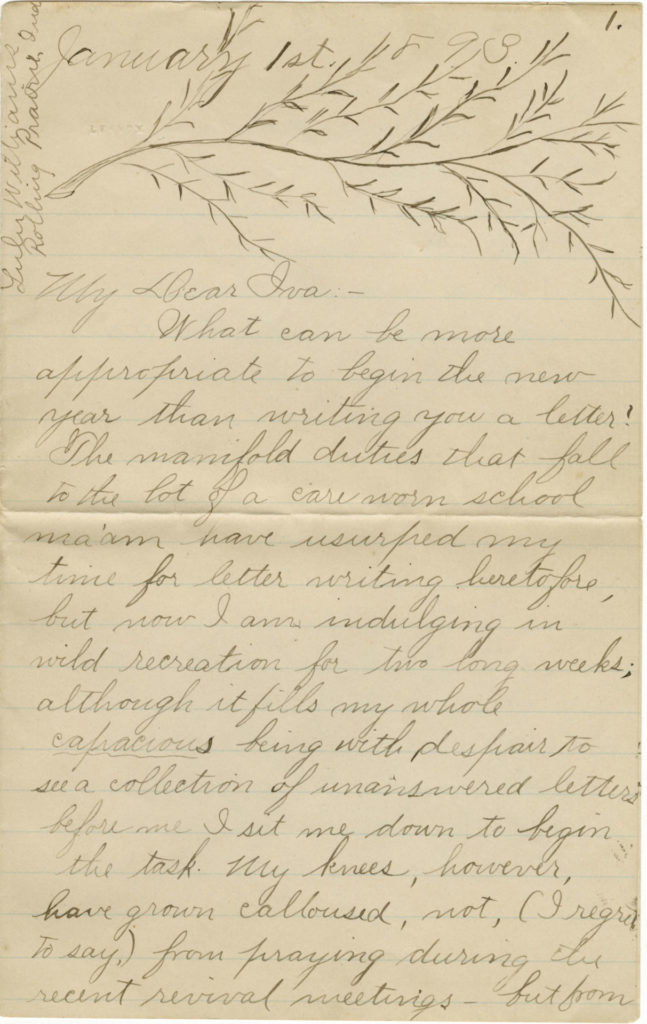

Iva clearly touched many people. Among her correspondents was Lulu Williams of Rolling Prairie, Ind., a fellow Normal School classmate. She wrote eloquently and extemporaneously, and it is easy to imagine how interactive and engaged the two women were through possibly years of lively correspondence. Given that both were educated young women, they may have had many ongoing conversations on topics of mutual interest. In a very full and decoratively adorned return letter Lulu wrote to Iva on January 1, 1893, her viewpoints on the questions of suffrage and equality were offered:

“I thank you also from your heroic argument concerning that all absorbing question dubbed ‘Wimmens Rights.’ I am glad to know that you have a mind of your own and that you express your opinions freely. Your chain of argument was splendid and I hardly feel capable of defending myself. I asked your opinions purely for information and I congratulate you upon your powers of oratory. Like yourself I am not ‘posted’ upon the issues of the day and I do not remember of ever reading an article about that subject. You gave me an insight upon the question that I never had before.”

“To begin, I honestly and sincerely think women should have the right to vote. What I want is the privilege, at least, then I can use my own discretion about voting. I think that woman’s principal work is that of home keeper, still I think she should have the power to vote if she so desired.”

Identifying as heroines a trio of women lawyers in the same family, Williams asserts that, “I think that not one of these young ladies is unfitted for a home because she has identified herself with an unusual calling for woman. No! the cry is for more such women!” She then adds, “The world is educated slowly by argument, quickly by events. Women have shown the world that they may wear laurels as doctors, lawyers, editors, journalists, etc., in fact nearly every thing from teachers to engineers and blacksmiths, and why not have women politicians? I can not see why widows and other ladies who own property and are taxed the same as masculine land owners are denied the privilege of woman suffrage. Woman has been defined ‘the highest type of man;’ if this be true (and I see no reason to the contrary), why is she held inferior to man? We all enjoy that sense of individual independence and like to be in subordination to no one. I consider you and myself as well qualified to vote. I think the time is coming when I (with the rest of my sisters who may desire) may walk up and cast our ballots with the brethren and not be considered unwomanly either. Maybe I am too radical – if I am please pardon me for I never was in but one debate. Woman has advanced silently, calmly through the past centuries, becoming more and more distinct through the twilight veil until she has reached the period on the threshold of which she now stands. I predict a bright future for her.”

Women campaigning for the right to vote, ca. 1905 Indiana Historical Society.

These letter extracts indicate that Lulu Williams clearly had much to say and held distinct opinions on many topics, as did Iva. Their assessments could have converged while not necessarily eroding their affections. It is likely the two women had a friendship and active correspondence that lasted several years, though the Iva Jordan acquisition is limited to only this one enticing letter from 1893.

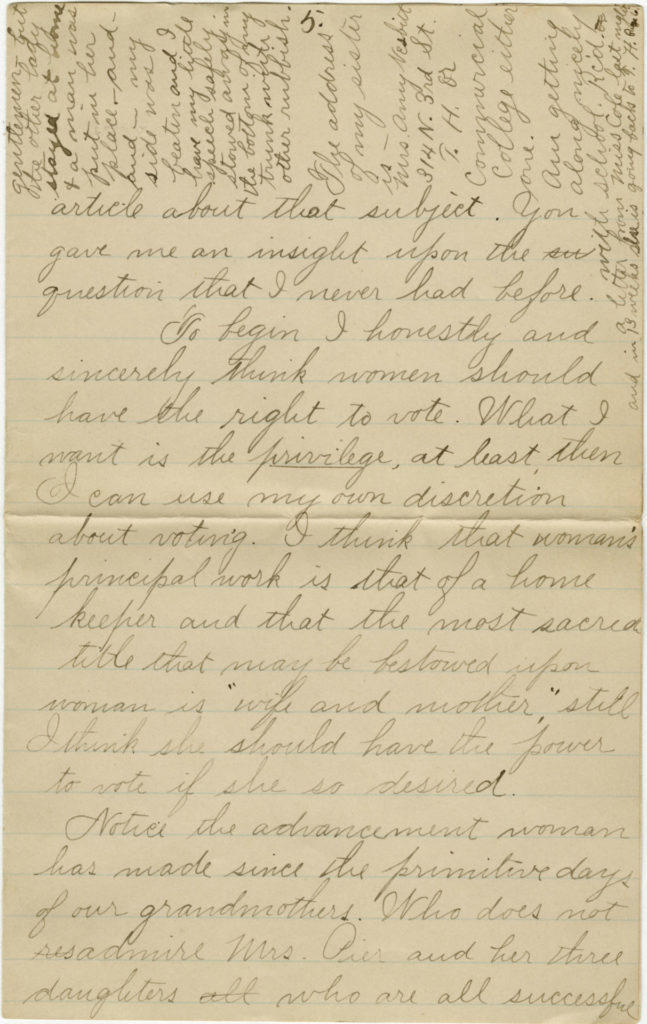

Some research into another associate and Vermillion County affiliate of Jordan’s, her student, Ernie Pyle, did yield some reflections revealing more about both individuals. In one of Pyle’s regular Dana-themed columns, “At Home,” published Sunday 19 November 1943, he reminisced both realistically and poetically about his former teacher after she had been stricken with a stroke resulting in her left side being paralyzed. She and sister-in-law, Bertha, lived a mile across the field from the Pyle family farm and had occasional hired hands to help with the farm. With World War II taking many of the young farmers, the women were in a predicament, Pyle observed, “and they can not get a man anywhere,” leaving Bertha with much of the responsibility. Iva was not able to help much physically, though the stroke failed to impact her face or her speech. Said Pyle, “She says maybe it would be a good thing if it had, for she just talks everybody to death. She says twice visitors have just got up and left after about 10 minutes with her, because she would not let them get a word in. But as she says, what is the use of having visitors if they will not listen to you.” This gives us a glimpse of the humor the two shared.

Miss Jordan’s most famous student wrote reflectively on her life and personality.

After Pyle’s own mother had been paralyzed by a stroke in 1937, he shared in his column, “The Roving Reporter,” that neighbors far and wide had come to help his ailing mother — including the Jordans: “Bertha and Iva Jordan came twice for half a day each. They brought two pies the first time and a cake the second time, and they did the washing and ironing.” Of his first schoolteacher, he reported: “She is gray-haired now, but she is still pleasant and soft-spoken as she always was. She wore an apron and a dustcap while she did the ironing in our kitchen. We talked about my first year in school, and we both hated to realize it was more than 30 years ago.” Through Pyle’s vivid reporting and memories, we see his rural schoolteacher as we can through no other available sources.

Iva Jordan died suddenly while at her doctor’s office in Terre Haute, 26 October 1944. One wonders how Ernie Pyle may have observed the occasion. Exhausted from war reporting at the time, he made a stopover in Dana in late September 1944 while reportedly headed for his New Mexico retreat to recharge and prepare for his next assignment in the Pacific theater. Perhaps he and Iva had one final visit, though tragically, Pyle was killed less than six months after his aging mentor had passed.

Pulitzer Prize winning war correspondent and journalist Ernest Taylor (Ernie) Pyle (1900-1945), Dana’s most famous son, was born on a farm outside of town. He is seen here with a bomber crew on Saipan in the Pacific in 1945. Indiana Historical Society

Jordan’s death notice in the Daily Clintonian observed that “her personal contribution to the war effort was the writing of hundreds of letters to her former students.” For a woman whose interests spanned literary, church and civic activities, it was surely among her greatest public services.

How I would love to find any extant correspondence or affectionate words she may have penned to Pyle. Wouldn’t that be great?