Plan your visit

Alex Vraciu and the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot

June 21, 2021

Early in the morning on June 19, 1944, a Japanese fleet under the command of Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa launched the first of four waves of attackers against the aircraft carriers of Admiral Marc Mitscher’s task force protecting American forces battling the enemy on Saipan in the Mariana Islands. The American admiral stood ready; he positioned a circle of battleships under Vice Admiral Willis Lee to protect the carrier groups with their heavy anti-aircraft fire. Fighter direction officers on the carriers received intelligence on the position and movement of the enemy’s aircraft through intercepts made by Lieutenant Charles Sims, who spoke Japanese. These reports were relayed to the circling Hellcats in the combat air patrol.

East Chicago, Indiana, native Alex Vraciu, a graduate of DePauw University, was on alert with other members of Fighting Squadron 16 on the deck of the aircraft carrier Lexington to backup the combat air patrol already circling overhead. Possessed with keen eyesight, quick reflexes, excellent shooting instincts, and a knack for finding his opponent’s weak spot, Vraciu had become skilled in the deadly game of destroying the enemy in the skies over the Pacific Ocean with thirteen kills to his credit. “That was our job,” he noted. “That is what we were trained to do. You can’t be squeamish about the thing or you don’t belong in a cockpit of that kind of an airplane [a fighter]. Nobody told you it was going to be an easy job.”

A Japanese torpedo plane is aflame after a failed attack on the escort carrier USS Kitkun Bay during the invasion of Saipan in June 1944. Library of Congress

At approximately ten o’clock a group of twelve Grumman Hellcat fighter aricraft—three divisions of four planes each—were launched from the Lexington. Over his radio, Vraciu received orders that the planes should take a heading of 250 degrees and climb to twenty-five thousand feet at full power. “Overhead, converging contrails of fighters from other carriers could be seen heading in the same direction,” Vraciu remembered.

The squadron’s leader, Lieutenant Commander Paul Buie, who flew a plane with a new engine, started to pull away from the other Hellcats. Vraciu experienced problems with his engine, as it threw a film of oil on his windshield, making it hard for him to see. His engine’s problems also limited his altitude to just twenty thousand feet. As the Hellcats climbed, Vraciu’s wingman, Ensign Homer Brockmeyer, repeatedly pointed toward his leader’s wings (he had to use hand signals because the flight was observing radio silence). Vraciu thought Brockmeyer had seen the enemy, but what Vraciu did not know was that his wings were not securely locked into place—a situation that “explained Brock’s frantic pointing.” (The Hellcats’ wings could be folded for easier storage below deck on a carrier.)

Vraciu’s group received orders to return to the task force and orbit overhead at twenty thousand feet. “The bogeys were seventy-five miles away when reported, and we headed outbound in hope of meeting them halfway,” he remembered. “I saw two other groups of Hellcats converging off to starboard, four in one group and three in another.”

About twenty-five miles from the fleet, Vraciu saw three enemy aircraft and closed in on them. Believing there must be more Japanese in the area, he used his excellent eyesight to pick out a large mass of at least fifty airplanes about two thousand feet below him, streaking toward the U.S. ships. “I remember thinking that this could develop into that once-in-a-lifetime fighter pilot’s dream,” Vraciu recalled.

Gift of Douglas E. Clanin, Indiana Historical Society.

The enemy formation, which included several Yokosuka D4Y Judy dive bombers with their two-man crews, did not have any Zero fighter escorts. Diving in for an attack, Vraciu noted out of the corner of his eye that another Hellcat had begun his run on the same Judy he had targeted for destruction. “He was too close for comfort and seemed not to see me, so I aborted my run,” he said. “There were enough cookies on the plate for everyone, I thought.” Flying under the formation, Vraciu got a good look at the enemy and radioed back to the U.S. fleet the composition of the attacking planes.

Pulling his Hellcat up and over the formation, Vraciu picked out another Judy to attack. “It was wildly maneuvering, and the Japanese rear gunner was squirting away as I came down from behind,” he noted. “I worked in close, gave him a burst and set him afire quickly. The Judy headed for the water, trailing a long plume of smoke.” Vraciu pulled up again and came in behind two other Judys, turning both into flaming wrecks. “The sky appeared full of smoke and pieces of aircraft as we tried to ride herd on the remaining enemy planes in an effort to keep them from scattering,” he added.

The enemy flew closer and closer to the American fleet despite the withering fire from the attacking Hellcats. Because the oil on his windshield restricted his vision, Vraciu worked in close to his next victim so he could get a clear shot. “I gave him a short burst, but it was enough,” he said. “The rounds went right into the sweet spot at the root of his wing. Other rounds must have hit the pilot or control cables, as the burning plane twisted crazily out of control.”

Vraciu headed next for a group of three Judys preparing to peel off for their bombing runs close to a group of American destroyers. As the first Judy began its dive, Vraciu noticed a black puff of smoke appear next to him, the result of anti-aircraft fire from five-inch guns on the destroyers. Disregarding the flak, Vraciu overtook the nearest bomber. “It seemed that I had scarcely touched the gun trigger when his engine began to come to pieces,” he recalled. “The Judy started smoking then began torching alternately on and off as it disappeared below me.” Another short burst at the other Judy “produced astonishing results,” said Vraciu. The plane disintegrated in a tremendous explosion that made Vraciu yank his plane about wildly to avoid hitting any pieces. “I must have hit his bomb, I guess,” he reasoned. “I had seen planes explode before, but never like this!”

With another Japanese destroyed, Vraciu radioed to the fleet: “Splash number six. There’s one more ahead and he’s diving on a BB [battleship]. But I don’t think he’ll make it.” The words had barely left his mouth when the remaining Judy caught a direct hit and blew up. “He had run into a solid curtain of steel from the battlewagon,” Vraciu noted.

Catching his breath, Vraciu looked around the sky and could see only American planes still flying. Looking back over the route his squadron had taken, he saw Hellcats and “a thirty-five-mile long pattern of flaming oil slicks.” In a matter of just eight minutes, Vraciu had downed six Japanese aircraft—a result that gave him a great deal of satisfaction. “I felt that I had contributed my personal payback for Pearl Harbor,” he said. This good feeling began to evaporate, however, when some “trigger-happy gun crews” from the American fleet mistook him for the enemy and started firing at him. He uttered a few choice words over the radio and was able to land his Hellcat with no further problems.

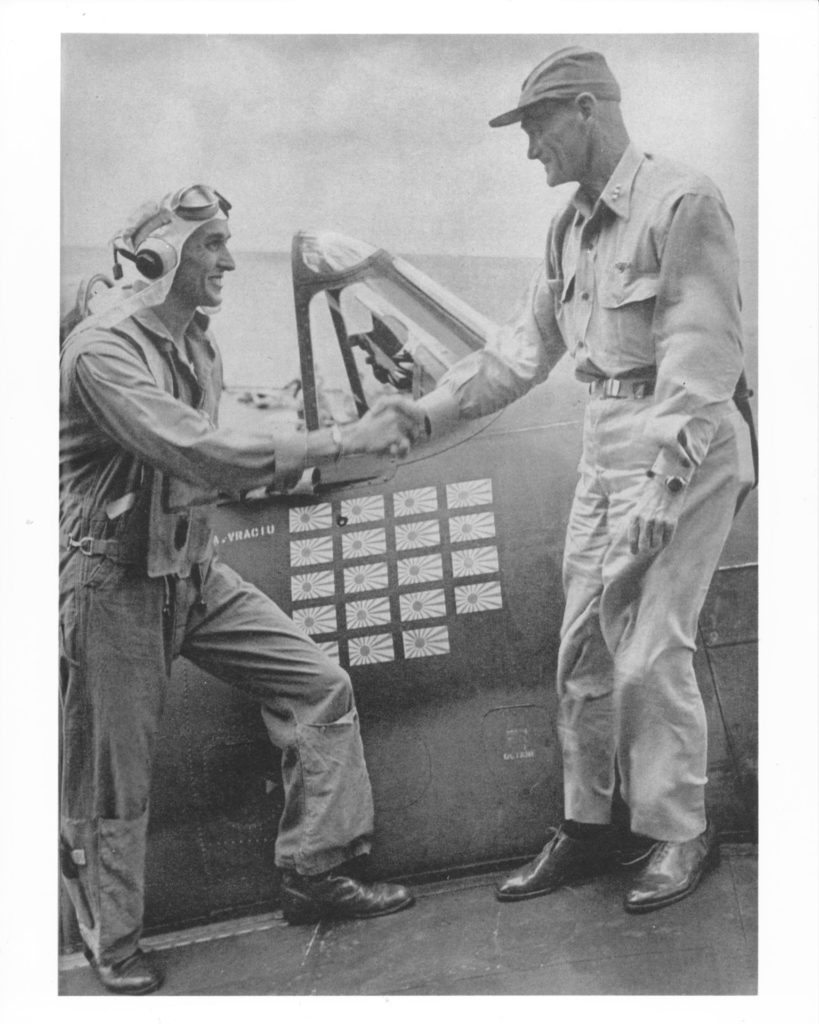

As he taxied up the deck of the carrier, Vraciu flashed six fingers to the bridge. The pilot repeated the gesture after exiting his Hellcat—a moment captured on film as he signed the yellow maintenance sheet near the tail of his aircraft. Although Admiral Mitscher was careful to stay out of the photographs being taken then, several days after the battle he noted: “I’d like to pose with him [Vraciu]. Not for publication. To keep for myself.” (Vraciu later named his youngest son, Marc, in honor of Mitscher.)

Admiral Marc Mitscher congratulates Alex Vraciu for his skillful flying during the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. The nineteen Japanese flags affixed to Vraciu’s fighter aircraft mark the number of enemy aircraft he had shot down. Courtesy Alex Vraciu

The crew that maintained the Hellcats discovered that Vraciu had used only 360 rounds of the 2,400 available in his fully armed aircraft to shoot down the six enemy planes. “As can be expected, there was a great deal of excitement later in the ready room—including the liberal use of hands to punctuate the aerial victories,” Vraciu remembered.

Other American squadrons enjoyed just as good a day’s shooting as had Vraciu and Fighting Squadron 16. During the four attacks made against Task Force 58, the Japanese had used 373 planes—only 100 survived to return to their carriers. Hellcats also shot down an additional 50 land-based enemy aircraft. The Americans lost only 29 planes in this lopsided affair. According to Vraciu, a junior lieutenant from his squadron, Ziggy Neff, had the perfect comment to make at the end of the day’s fighting. “He apparently came from a hunting background and just happened to use that hunting jargon phrase in his post-flight briefing, saying, ‘It was just like a turkey shoot!’” said Vraciu.

The phrase stuck, and the battle became known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.