Plan your visit

A Myriad of Stories Weaves the Fabric of the 1818 Saint Marys Treaties Saga

September 1, 2020

If you are one of the nearly 4,000 readers of the Indiana Historical Society’s award-winning journal The Hoosier Genealogist: Connections, you may already be familiar with a stunning four-part series by A. Andrew Olson III, “The 1818 Saint Marys Treaties.”

Stunning is not too strong a word for Olson’s work, published from the Fall/Winter 2017 issue through the Spring/Summer 2019 issue. Olson dug deeply into primary sources to discover many of the individuals involved. History buffs may know the names of such Indian agents as John Johnston or governors such as Lewis Cass of Michigan and Jonathan Jennings of Indiana. Delaware Chief William Anderson and Miami Chief Jean Baptiste Richardville are also familiar names. But do you know of Potawatomi Chief Metea or missionary Thomas Dean? Have you heard of the York Indians?

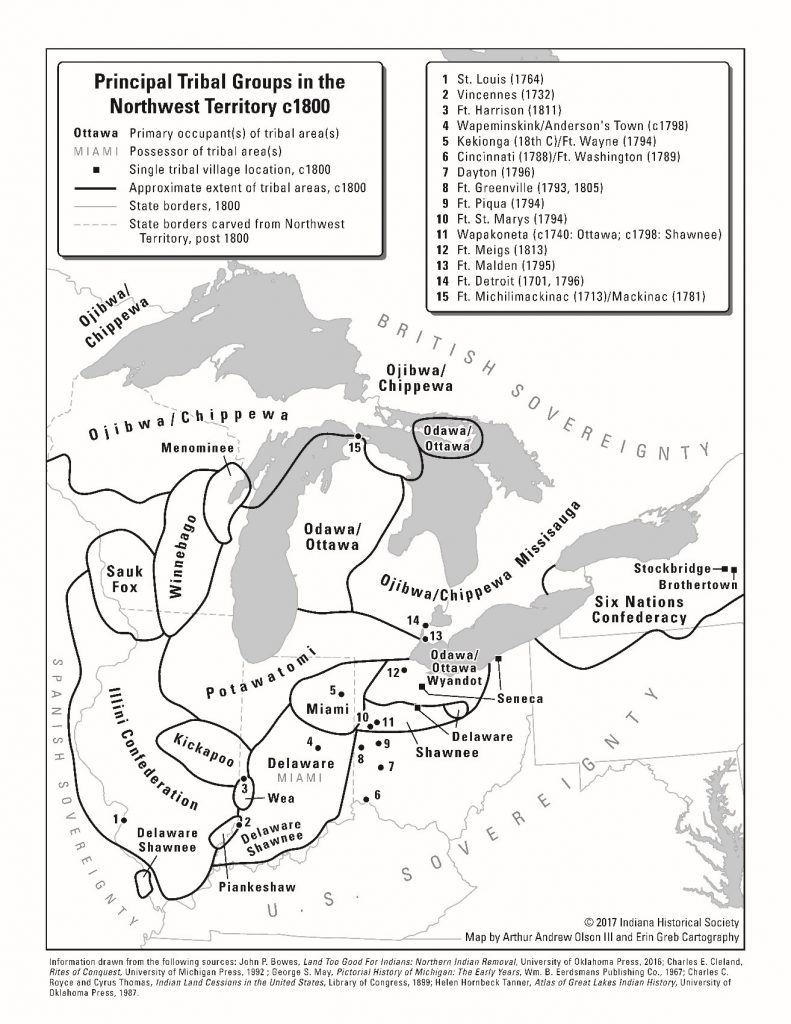

Olson found a myriad of persons and their interests, fears, and motivations regarding land in the Old Northwest during the decades when Indians lived in villages throughout Ohio and Indiana, just as American pioneers started across the Appalachian Mountains and down the Ohio River and started trekking northward. We know of the clashes; we know of policies to turn Indians into individualistic, capitalist, Christian Americans. But Olson shows us the toll the settlers wrought on the indigenous people who clung tightly to their ancestral homes.

Olson even brings into view a couple of handfuls of people known as Stockbridges and Brothertowns from the Indian reservations of New York State, Christianized Indians who were kin to the Delawares living in central Indiana. Frontier Indiana was thought a haven by natives for a moment in history. They thought themselves safe by moving west of Ohio, which was rapidly filling with settlers. During this moment, the Delawares extended a hand of friendship to their brothers in New York, inviting them to move to a land where Americans would not overrun them. The Delawares did not have time to sink down roots, however, before the government agents and the settlers started surrounding them. When the Stockbridges and Brothertowns arrived, the Delawares had already moved west, beyond the Mississippi River—the first of all the American Indians to do so.

The 1818 Treaties of Saint Marys, Ohio, while a catalyst for Indian removals, was not the reason the Delawares moved. As Olson poignantly describes: “The Delawares were desperate. They were racked by alcoholism, in grinding poverty and hunger, undermined by incessant white settler encroachments, and torn apart by nativist groups that promoted a return to the tribe’s pre-European culture, on the one hand, and Christian revivalist groups, on the other hand.”

Before this point of no return, Olson vividly paints a landscape swirling with change, of agents working for the American government who deeply respected and felt compassion for the indigenous peoples under their jurisdiction. The story gets dark quickly as treaties that gave Indians the right to swaths of land were rejected by the U.S. Congress. Instead the agents were compelled to negotiate and barter with, bribe, and finally swindle the rightful owners of the Old Northwest to gain millions of acres of land for American settlement because Americans did not want the tribes to own land or even to reside on land east of the Mississippi River.

The Delawares’ story is just one of many in the Saint Marys Treaties saga. Olson’s series introduces individuals from many tribes: Shawnees, Weas, Potawatomis, Wynadots, Miamis and others. It sets the late-eighteenth century stage for each, tells where and how the different groups were living, what they were paid and promised for their lands, and where and when they were removed. It also tells of those families who struck deals to stay in their homelands or on reservations east of the Mississippi.

Olson’s article series offers a rare depth of firsthand detail about the Saint Marys Treaties and their aftermath from the perspective of the American Indian groups and individuals in the Old Northwest, as well as from the government agents and missionaries. Richly informed by primary sources, the series is also set squarely within both the historical and latest scholarly works on the subject. Because of its significance for those interested in the history of American Indians, particularly of Indiana and Ohio’s natives, as well as for future research, the Indiana Historical Society has brought the four parts of the series together into one work. It is published and available for free in the IHS digital collections.

Enjoy reading “The 1818 Saint Marys Treaties” here.