Purchase Tickets

Where There is Food, There is a Farmworker

March 18, 2022

Indiana’s history is deeply rooted in agriculture from family farms to large-scale corporations, the last week of March is National Farmworker Awareness Week, recognizing their contributions and current issues they face. For over 100 years, foreign farmworkers would be a part of Indiana’s agricultural history. From beets to beef cattle, there is more than corn in Indiana, and where there is food, there is a farmworker.

Farmworker Definition

To understand who a farmworker is in this context, it is important to understand that there are two types. There are migrant farmworkers and seasonal farmworkers. The difference is that migrant farmworkers live in a different state or country where labor contracts allow them to follow the seasons, planting and harvesting crops. Seasonal farmworkers permanently reside in the same area or state. Present collective memory assigns a cultural identity as to who and where our nation’s farmworkers come from. Historically our nation’s farmworkers (also known as stoop laborers or field hands) have come from countries of both western and eastern hemispheres, whose skill and knowledge enriched our nation’s agronomy for centuries.

Asian Agricultural Workers in Stockton, California, 1930s

Takuya Sato Collection, IHS.

1918-1942: History of U.S. and Mexico Diplomatic Relations in the name of War Relief

Out-of-state and foreign farmworkers (especially those of Mexican or Mexican American heritage) have been cultivating Indiana crops for more than a century. In 1918, during World War I the U.S. government formed a binational agreement with Mexico for laborers in the name of war relief. Mexico would supply relief workers to work on our nation’s railways, fields, canneries, steel mills, packing houses and factories. This was made possible by departmental order no. 52461/202. U.S. labor agencies in places like El Paso, Texas, shifted the flow of both seasonal, migrant, and foreign workers from the south and southwest to the Midwest. This bracero program would end in 1921.

However, in 1924 an immigration quota was placed on eastern and southern European immigrants, based on previous national origin numbers. A non-quota status was given to all the countries in the western hemisphere. The non-quota status was cited as essential in the name of Pan-Americanism. The quota system coupled with the series of Chinese exclusionary laws, the demand for temporary foreign low wage labor furthered supported the need of Mexico’s laborers.

Initiating the Midwestern Mexican diaspora, which began in 1918.

This guestworker program later helped to set up the legal framework for the World War II-era temporary worker arrangement called Bracero Program (1942-1964), established by the Mexican Farm Labor Program. This was the second time Mexico and the U.S. formed a binational labor agreement in the name of war relief. However, Mexico and Mexican Americans would not be the only Latinos to contribute as low-wage skilled laborers supporting the U.S. agricultural sector. Puerto Ricans, who were U.S. citizens, would work alongside their Latin American brethren.

Antonio Media receives a retirement watch from an Inland Steel Company executive in 1959. Maria Picón Reyes Family Collection, Michaelene Olguin-Rivera, IHS.

From Charity to Advocacy: The Formation of Farmworker Unions and Farmworker Agencies

In 1968 Cesar Chavez marched with Filipino and Mexican farmworkers in Delano, California, and organized a boycott on behalf of grape workers. Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta would later co-found a labor organization called the National Farmworkers Association, later known as the United Farm Workers (UFW). They advocated for the improvement of the social and economic issues that affected farmworkers and their families. Farmworkers often brought along the family, following the agricultural seasons. From the early twentieth century to the 1960s there was a dramatic shift from charity to advocacy regarding farmworkers and their needs. Migrant ministry groups organized by local churches and their volunteers would initially address the needs of farmworkers and their families. The catalyst for this shift would come in 1964 via President Johnson’s nation war on poverty initiative through Economic Opportunity Act. This provided the financial framework via federal funds to helped to start new organizations that effectively addressed the conditions that perpetuated poverty. Specifically, Title III-B grants through the Office of Economic Opportunity moved local initiatives forward by creating new solutions to address the root causes of poverty.

Indiana: Associated Migrant Opportunities Services, Inc. (AMOS), 1965-1976

In central Indiana, local churches and small organizations met the immediate needs of farmworker laborers. In 1965 Associated Migrant Opportunities Services, Inc. (AMOS) would be incorporated by the Indiana Council of Churches, the Roman Catholic Archdioceses of Indianapolis, Lafayette, Gary, and Ft. Wayne South Bend. Tulio Gulder, who also helped co-found the Hispano-American Multiservice Center (presently known as La Plaza, Inc.) in 1971 would initially lead the statewide effort as Executive Director. There were many leaders who were initially working as pioneers in their local communities prior to AMOS, most notably Carmen Velasquez, of the AMOS East sub-office in Marion. AMOS, Inc. worked on breaking the cycle of poverty by providing vocational training, English lessons, legal aid, housing opportunities, and enforcing state health department standards of living quarters in labor camps. Prior to its founding, labor camp living quarters did not always meet state-regulated health standards.

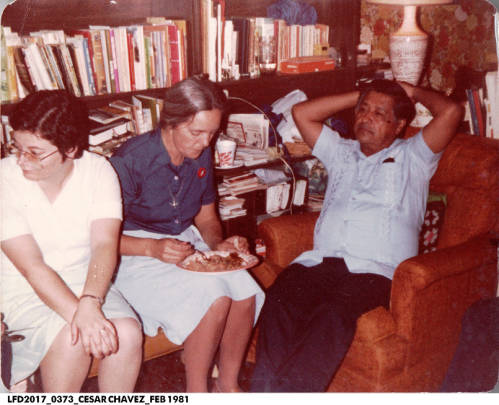

Sister Mary Soledad Velasquez (in blue) of the AMOS East sub-office with Cesar Chavez (below), 1980s. Velasquez Family Collection, IHS

Cesar Chavez (right) at the AMOS East sub-office in the 1980s. Velasquez Family Collection, IHS.

By 1970 AMOS had information centers in Hammond, South Bend, Fort Wayne, Marion, Kokomo, Muncie and Sweetser. They had workers, without information centers, in Franklin, Sunman, and Columbus. This same year it was estimated that Indiana had close to 300 labor camps across the state. At the peak of the season, they employed 14,000 workers to pick tomatoes, 2,400 on pickle crops, 2,100 in seed cornfields. Smaller crops worked were sweet corn, onions, and potatoes by roughly several hundred individuals.

Additionally, by 1970 AMOS helped over 800 families (roughly 1,600 individuals) to settle out of the migratory stream to buy homes via FHA or VA loans. The International Council of Churches also provided day centers for children, to keep them out of the fields. In later years mechanization of farmworker labor reduced the number of laborers in Indiana’s fields. AMOS, Inc. ceased operations due to the loss of federal grant funds from the U.S. Department of Labor in 1976.

Currently, temporary foreign agricultural workers are supported by H-2A program.