Purchase Tickets

What History Tells Us: Historical Facts AND Public Interpretation

April 3, 2019

History Matters is a blog series where we’ll be talking about the things you’re not supposed to discuss at the dinner table – things that may make some people uncomfortable. These pieces of our history are there if you look but might not be top of mind or in a textbook. We often think of history on a larger scale, but let’s remember that history happened here. It happens every day. And it matters.

There is a gray area swirling where historical facts and public interpretation meet. It is often difficult to keep all the hour-by-hour, day-by-day events in mind when considering a large historical topic, such as slavery. Many people do not know the details of how slaves were freed, or they knew once but tend to think of it in shorthand now – when they think of it at all. Even historians can miss the exact truth of this matter when weeding through material related but not directly linked to the emancipation of American slaves. Unless our field is mid-19th-century American history or African American history, it is easy, along with the general public, to think or blindly accept a statement that Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves.

This happened recently to me with an article in the Fall/Winter 2018 issue of THG: Connections about the Underground Railroad in Jennings County in southern Indiana. The state’s UGRR operations are today under intense research and scrutiny. Historians want to make sure we gather facts and evidence and bring true stories together to interpret the larger story of the UGRR. It is an important task – to find and share the quintessential American saga of those who first helped free the slaves. One “myth” that has been debunked in this new process of systematically gathering primary sources on the UGRR is the preeminence of whites in the Underground Railroad’s clandestine, illegal activities. Increasingly we see that many more blacks than whites helped enslaved people move from the lands of slavery to lands where they could be free.

Still, the importance of the UGRR as a topic is no excuse to overlook another historical “myth” when it is used to tell the UGRR story. As editor of Connections, I accept full responsibility for the oversight.

And yet, it got me thinking. When talking about history, I always start with a discussion about what history is. History is not only what happened. It is also what witnesses thought happened at the time and what people have thought about what happened since.

In the slice of history that addresses emancipating slaves, it’s proper to talk about all the laws, people and events that led to it, starting with abolitionists and slave owners who brought their slaves to freedom in northern states. It should encompass the UGRR and would talk in painstaking detail about Union military leaders who declared slaves were emancipated in areas they had conquered and efforts by the U.S. Congress to pass laws granting limited emancipation of slaves who were owned by Confederates. Lincoln’s progression of thinking and acting toward his Emancipation Proclamation, which only freed slaves in the Confederate States, should also figure in the discussion. It would end with the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in December 1865 – months after Lincoln’s death.

Reminded of the facts, I am nevertheless struck by the iconic reality of the American people’s interpretation of what ended slavery – Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Although not true technically, this wonderfully brave declaration did free a lot of slaves, paving the way for all slaves to be freed by Congress and through the winning of the Civil War. It is a lesson in getting the facts straight AND acknowledging what history means to the public. The Emancipation Proclamation is the lens through which many Americans and others view the American Civil War. There are other lenses, each as iconic in their own ways. The facts themselves are still debated, but the icons are pretty solid at this point. That may change in the future, but for now many look to Lincoln’s proclamation for meaning in a bloody war. For these individuals, it gives this war a purpose and a redeeming outcome.

While it is important for historians to gather the details and tell the stories of history as accurately and completely as possible, it is also very important to recognize, acknowledge and examine how everyday people interpret the history handed down to them. What treasures, lessons and meaning do they take away? How do they use the history of their forebears to make new history? I would wager that, more often than not, people act upon their interpretations of history rather than on the finer and truer details of history. What responsibilities, then, do public historians carry?

I’m sensing a two-edged sword here. If we understood in day-to-day detail how Adolf Hitler came to power, we may be better equipped to stop another Hitler from wielding power. But, if we “believe” in the power of the Emancipation Proclamation, it may help us free more people. And so, the middle ground between academic and public interpretation swirls around us. There is not a stand-off between these views, but rather a sharing of two different kinds of important information. One is fact-based and one is action based. They feed each other. What public historians must do is be aware, see as clearly as possible, be skeptical, distinguish between evidence and interpretation. And just as crucial, we must keep open a welcome place where ideas, facts, and reactions can meet to discern not only the truth but the way forward.

This realization underscores the relevance and importance of the Indiana Historical Society and other museums, archives and historical organizations that provide this common ground. They are not only places where public historians teach but also places where these professionals grow insight through their preparations for and their interactions with the public.

Further Reading

William A. Blair and Karen Fisher Younger, eds., Lincoln’s Proclamation: Emancipation Reconsidered (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009)

Allen Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004)

Louis P. Masur, Lincoln’s Hundred Days: The Emancipation Proclamation and the War for the Union (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 2012).

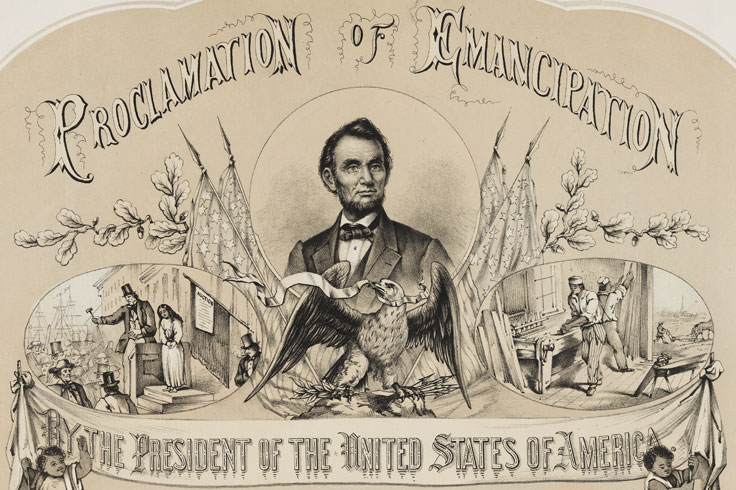

Image

From a broadside of the Emancipation Proclamation created by B. B. Russell and published in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1868 (Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana)