Purchase Tickets

Two Old Birds

June 24, 2021

General William Henry Harrison was a senator, Indiana territorial governor, and president, but many forget that “Old Tippecanoe” was also a minister in South America. By the time of his presidential election, the only reminder of this experience was a colorful bird he’d brought back in 1830, a macaw described in a letter by family friend Catherina Bonney as “quite tame” as it flew “to the top of the lofty trees.”

To her surprise, the bird made “the most unearthly croaking noise or scream so shrill” (Bonney, 1875). The macaw’s owner was also known to squawk in order to be noticed. Harrison’s constant preening for official appointments was done to support his loved ones. Tragedy continually visited his family, and his house on the Ohio River filled with displaced grandchildren and in-laws, some of them in debt. But for the success of his farm, the Harrisons would have nothing to eat. Knowing this, the general’s large flock of companions would descend on hapless employers to secure his employment. In 1828, the victim was President John Quincy Adams, from whom Harrison received his appointment as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Republic of Colombia, a job that paid today’s equivalent of $250,000 annually. On November 11, he took his 18-year-old son Carter and Kentuckian Secretary Edward Tayloe with him aboard the war sloop “Erie” to begin his journey (Green, 1941).

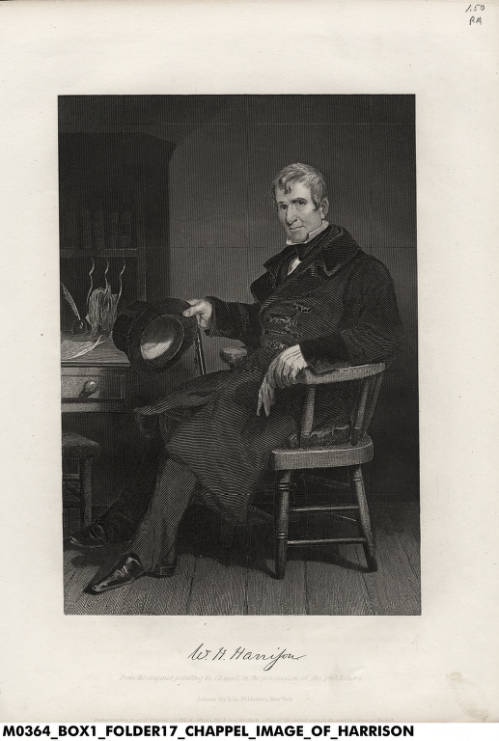

An engraved portrait of William Henry Harrison produced from the original painting by Chappel, which was in the possession of Johnson, Fry & Co. Publishers, New York.; Indiana Historical Society.

Colombia was a temporary state encapsulating present-day Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and Venezuela. The boundaries were set by a government forming under General Simon Bolivar, called the George Washington of South America, “the Liberator” who defeated the Spanish colonizers with his patriot army. The temporary government was disorganized and corrupt, however, and rumors emerged that Bolivar wanted to establish another European monarchy while insurgents fought against him to promote a republic (Goebel, 1926). General Harrison officially stepped onto South American soil with Carter and Tayloe on December 20, spending the holidays trekking in the direction of Bogota on horseback through Venezuela and Cucuta. He wrote his wife Anna later that his baggage was hauled “on men’s and women’s backs…, sixty miles over…horrible roads” (Green, 1941, p 266). Biographer Dorothy Goebel described the scene as the entourage made their way to the city of Bogota:

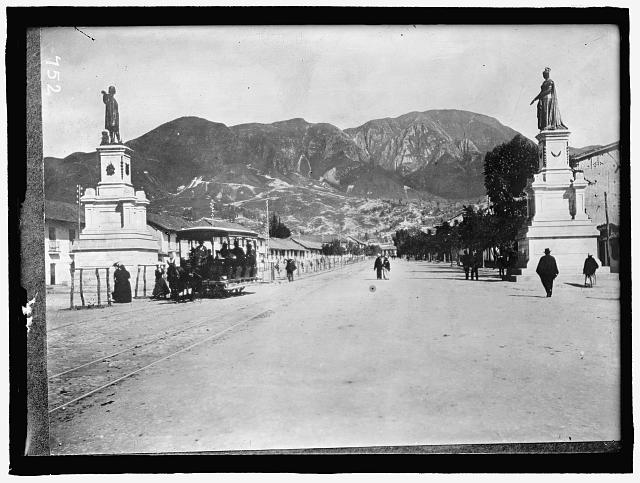

Colombia, street scenes in Bogota; Library of Congress

Near the coast and along the river(-)ways were deep forests filled with brilliant-plumaged birds and droves of chattering monkeys. The very trees and flowers were strange, and the towns, modeled on the Spanish plan, had the exotic charm of the unfamiliar. The latticed houses, the ornate churches, the open squares of the towns where dancing and gambling were kept up all night during a fiesta, were all suggestive of the Old World” (Goebel, 1926, p 257).

26-year-old Rensselaer, son of Harrison’s longtime military friend Solomon Van Rensselaer, joined the group in June and corresponded extensively. To his father, he described the House of James, where Harrison stayed, as having an oversized parlor and “more room than he requires,” with a large garden “in which he takes much delight.” Local corruption was brought to Harrison’s doorstep along with his baggage; half of his dinnerware had been stolen in transit. The climate was no better for him, as the humidity and altitude were contrary to his health. On a positive note, his U.S. legation was surrounded by ministers from around the world. Balls, parties, and even horse races were enjoyed in town in the Colombian capital, while in his spare time Harrison considered adopting native plants and earthen fences for his Ohio home. At a fateful dinner with the Bishop of Carthegena, he toasted the people of Colombia, inviting them to follow the example of his country, and his words led to whispers of conspiracy against local government. If this wasn’t bad enough, his rival Andrew Jackson had just been inaugurated president and recalled Harrison to home early (Green, 1941).

In the end, Harrison, his son Carter, Tayloe and Van Rensselaer barely escaped Bogota on the backs of mules before local officials could arrest them. In Guaduas, the group engaged a flatboat to take them down the Magdalena River to their destination, and the old general exploded when the vessel docked and the crew wandered off. His patience at an end, Harrison swung his cane, threatening to break bones if they weren’t recalled. Then he persuaded the passengers to “Cast off the line then and let the damned rascals stay where they are” (Green, p 282). Once in Carthegena, the group realized that the Natchez never received the note Harrison sent before leaving Bogota, and the weary group was stranded for two months before merchant Silas Burrows gave them—and the macaw—passage to New York aboard his ship called the Montilla (Green, 1941).

Harrison was abandoned by the administration at the end of his quixotic foray. But the macaw remained his faithful companion and lived for over a century, dying in the 1940s. Fifteen years after the expedition, Old Hickory’s African Gray Parrot avenged Old Tippecanoe by mimicking the colorful language it learned at the Hermitage. In 1921, 92 year-old Rev. Normont recalled attending Jackson’s funeral as a boy.

He wrote that, “while the crowd was gathering, a wicked parrot that was a household pet got excited and commenced swearing so loud and long as to disturb the people and had to be carried from the house” (Heiskell, 1921, p 53).

The squawking birds got the last word, after all. For all their fame, neither president outlived them.

SOURCES

Bonney, C.V.R. (1875). A legacy of historical gleanings, vol. II. J. Munsell 82 State Street

Green, J.A. (1941). William Henry Harrison: His Life and Times. Richmond, VA: Garrett and Massie, Inc.

Goebel, D.B. (1926). William Henry Harrison: A Political Biography. Indiana Library and Historical Department.

Heiskell, S.G. (1921). Andrew Jackson and early tennessee history, vol. III. Ambrose Printing Company