Purchase Tickets

The Story of a Debonair Grifter, Stew Donnelly

June 8, 2021

“When we think of cheese, it’s Wisconsin; […] but with grifters, it’s Indiana.” So wrote linguistics professor and con man expert David W. Maurer in his popular 1940 book The Big Con. Among the very best of these criminals with the light touch and cultured manner, Maurer names longtime Indianapolis resident Stewart C. Donnelly, who had a reputation across two continents as a master card sharp and roper.

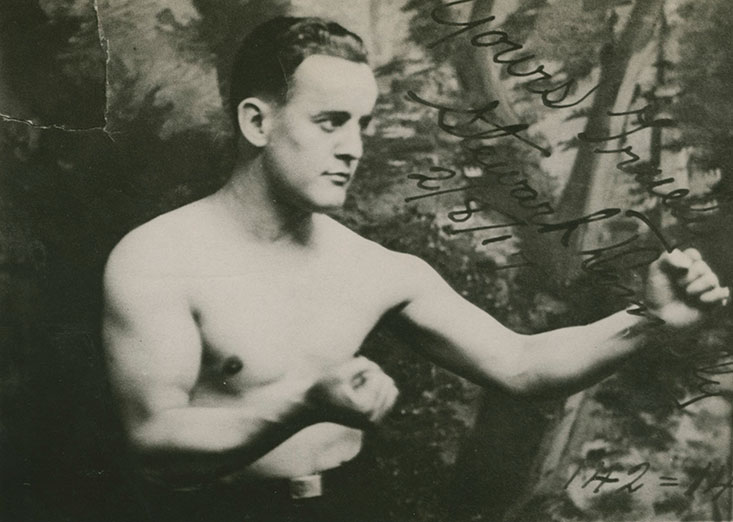

The Indiana Historical Society holds several photographic portraits of the debonair Stewart Donnelly in the collected papers of journalist Wayne Guthrie. Guthrie’s column “Ringside in Hoosierland” ran in the Indianapolis News for 30 years.

Stewart “Stew” Donnelly was born in Iowa in 1889 but came to Indianapolis at the age of eight, where he attended St. John’s parochial school. As a young man, Donnelly regularly appeared in the boxing ring as a welterweight, fighting such contemporaries as “Battling” Nelson and Indianapolis’ own Chuck Wiggins. He claimed to have trained Jess Willard for his fight against Jack Johnson and was in Willard’s corner during his 1919 fight against Jack Dempsey.

Stew Donnelly the pugilist in 1917. Wayne Guthrie Papers

When prohibition came on, Donnelly saw an opportunity and embedded himself in the lobby of the luxurious Claypool Hotel. From there he supplied bootlegged beverages to thirsty officeholders from the nearby Statehouse. But Donnelly himself had no taste for liquor. In fact, the ex-boxer was known to abstain from tobacco, drugs, and alcohol. He did, however, have an eye for the extravagant lifestyle of the many confidence men he knew. Evidently, they saw potential in the good-natured Donnelly and took him under their tutelage.

A good roper like Stew Donnelly had the gift of gab and could impress a stranger with his friendliness and trustworthiness. Having secured the stranger’s confidence, he then “roped” him into a poker game in which the stranger (or “mark”) invariably had no chance of winning. For many years, Donnelly successfully plied his trade on ocean liners and in upscale hotels on both sides of the Atlantic. He boasted that he had taken in more than $2,000,000 during his career. Any time he was picked up, like the time in 1933 when he was briefly questioned in connection with the Lindbergh kidnapping, police departments “from the Riviera to Reno” lined up with charges against him.

By 1950, Stew Donnelly had retired and could once again be found lounging around the elegant lobby of the Claypool. He died after a heart attack in 1957. A decade later, a fire caused the already ailing Claypool to pass into history as well. But both survive, along with untold other surprising and colorful characters, in the archives of the IHS.