Purchase Tickets

The Speech – Robert F. Kennedy, Indianapolis, and the Death of Martin Luther King Jr.

March 31, 2022

The crowd that gathered at the Broadway Christian Center at Seventeenth and Broadway Streets on Indianapolis’s near northside for an outdoor rally on a cold and windy evening on April 4, 1968, appeared to be in a festive mood despite the weather and late hour. They were going to be among the first in the Hoosier State to hear remarks from a newly declared Democratic presidential candidate, U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York.

Most who had gathered in this majority Black neighborhood, however, had not yet heard the horrible news that, earlier in the evening, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr, had been gunned down by an assassin outside of his hotel room in Memphis, Tennessee.

In the crowd, estimated in size anywhere from 1,000 to 3,000 people, there were individuals who were there for various reasons. Abie Robinson, who the year before had completed his service with the U.S. Navy, had gone to the Broadway Christian Center not for any political reasons. “I was a twenty-four-year-old young man,” he recalled. “I was hoping to meet some girls there.”

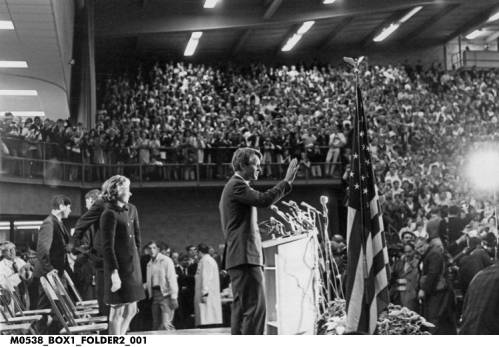

Robert F. Kennedy Speaks in Indianapolis, 1968 (Indiana Historical Society)

The African American veteran had come home to Indianapolis to witness on his television screen images of a country in turmoil over racial issues. “I found out the things that were happening—the bombings. I didn’t know the people in Alabama had killed five kids, didn’t realize the dogs and all that. It infuriated me. You leave the military and come back to your country and find out that’s what was happening,” Robinson noted.

As volunteers worked at tables to register voters, a band played, and spectators waved banners and signs supporting Kennedy’s candidacy, two white, sixteen-year-old North Central High School students, Mary Evans and Altha Cravey, milled about with the rest of the audience, who were, as one participant described it, “packed in like sardines” near a flatbed truck from which Kennedy was supposed to speak. Like many young people during that political season, Evans and Cravey had become transfixed by the antiwar candidacy of U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy, the Minnesota politician who had decided to take on incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson to protest America’s involvement in Vietnam.

Inspired by their growing disgust with the war and McCarthy’s commitment to ending the conflict, the students had volunteered to work for his campaign in Indiana, where he was running in the primary against both Kennedy and Governor Roger Branigin. Despite their allegiance to McCarthy, Evans and Cravy, because of their keen interest in politics and public policy, had come to hear what Kennedy had to say.

There were some gathered in and around the crowd, however, who had grown tired of the choices offered by America’s two political parties and were looking for more radical change. Several local black activists had heard of King’s death and were gathering support in the African American community for violent action.

William Crawford, who went on to a distinguished career as an Indiana legislator, was at the time of Kennedy’s appearance a member of an organization known as the Radical Action Program. He and his friends were very close, he recalled, to resorting to violence as a way register their grief and rage about King’s assassination. One estimate had close to 200 militants sprinkled throughout the crowd. Those responsible for local arrangements for the speech, including respected Black Power leader Charles “Snooky” Hendricks, grew so fearful that Kennedy’s life might be in danger that they recruited people to check the area for possible assassins. “There was a lot of anger and frustration that Dr. King, whose message was one of non-violence and working within the system, was the victim of that kind of racism,” Crawford remembered. “Dr. King is dead and a white man killed him!” a black woman at the site cried out. “Why does he [Kennedy] have to come?”

The potential for violence had some Indianapolis city officials worried. Michael Riley, an Indianapolis attorney and chairman of the Indiana committee to elect Kennedy, received a phone call from Mayor Richard Lugar urging that the rally be canceled for fear of a riot breaking out when the crowd learned King had been murdered. “I really was very, very fearful about the life of Robert Kennedy and the lives of everybody else who was going to be involved in this,” Lugar later said. To have Kennedy proceed with his speech could potentially court disaster. City officials had even threatened Riley that the fire department would string their hoses across the streets leading to the rally site to stop people from attending. Indianapolis’s chief of police warned the Kennedy campaign staff that he could not guarantee the senator’s safety if he decided to go ahead with his speech.

Kennedy had come to the Hoosier State to kick off his campaign to win the Indiana Democratic presidential primary. Before traveling to Indianapolis, Kennedy had made two other campaign stops that day, one at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, and another at Ball State University in Muncie. During a question-and-answer session following Kennedy’s Ball State speech, a young black man had asked whether the candidate could justify his belief in the good faith of white people toward minorities. Kennedy answered that most people in the country wanted to do “the decent and the right thing.

Robert F. Kennedy Speaking at Ball State University. Indiana Historical Society

As Kennedy boarded the plane for Indianapolis to formally open his campaign headquarters on East Washington Street and to make an appearance at Seventeenth and Broadway, one of his key supporters in Delaware County informed him that King, who had traveled to Memphis to offer his support for the city’s striking black sanitation, had been shot.

After arriving at Indianapolis’s Weir Cook Airport, Kennedy learned that King had died. Thinking back to the answer he had given to the black student at Ball State, a distraught Kennedy told a Newsweek reporter that it grieved him that he “just told that kid this and then walk out and find that some white man had just shot their . . . spiritual leader.”

Kennedy decided to cancel his appearance at his downtown campaign headquarters but to proceed on to Seventeenth and Broadway as planned. He did, however, send his wife, Ethel, on ahead to the Marott Hotel on North Meridian Street. After a brief statement on King’s death to the press assembled at the airport, Kennedy climbed into a car that would take him to the rally. “He had no prepared speech,” said Fred Dutton, Kennedy’s right-hand man for much of the campaign. “He had planned a fairly standard stump talk.” On the approximately twenty-five-minute drive from the airport, Kennedy sat alone in the back seat staring out of the window at the dark city and attempting to find the right words for the occasion. “What should I say?” he asked. “I made a couple of inadequate responses,” Dutton remembered responding. Kennedy managed to scribble out a few ideas for his talk on the back of the envelope.

Seen here with aide Fred Dutton, Kennedy won the Indiana primary, defeating Indiana governor Roger D. Branigin, who placed second, and McCarthy, who finished third. After eking out a close victory over McCarthy in California, Kennedy was shot by an assassin. Kennedy died on June 6, 1968. Bass Photo Co Collection, Indiana Historical Society

John Bartlow Martin, an Indianapolis native and close adviser to Kennedy during the campaign for the Indiana primary, had returned to the Marott from dinner, where he had gone with Kennedy speechwriters Jeff Greenfield and Adam Walinsky after hearing a report from a secretary that King had been shot. Walinsky received a call that King had died. At the hotel, Martin saw a local police inspector parked at the curb. He went up to the car and asked the officer if the candidate should go ahead and address the crowd. “He said, with a fervor I imagine was rare in him, ‘I sure hope he does. If he doesn’t, there’ll be hell to pay,’” Martin remembered. Walinsky went with the inspector to the rally site to make sure Kennedy knew King was dead, while Martin and Greenfield worked on a draft statement on King’s death. (They later “threw their drafts away” after learning what Kennedy said at the rally.)

Arriving at Seventeenth and Broadway, Kennedy, wearing a black overcoat that once belonged to his brother, John, climbed onto the bed of the flatbed truck located in a paved parking lot near the Center’s basketball court. After asking for those waving signs and banners to put them down, he informed them that King was dead. The audience, which had been anticipating a raucous political event and for the most part had been unaware of the shooting, responded to the announcement with gasps, shrieks, and cries of “No, No.” Tom Keating, a reporter for the Indianapolis Star, had raced to the scene with two policemen. He noted that the crowd reacted to the news almost like “a wounded animal” and called the event one of the most “supercharged” he had ever witnessed.

Robert F. Kennedy Announcing Martin Luther King’s Death

Indianapolis Recorder Collection, Indiana Historical Society

Facing the now stunned and disbelieving audience, some of whom were weeping at their loss, Kennedy gave an impassioned approximately six-minute speech on the need for compassion in the face of violence that has gone down in history as one of the great extemporaneous political speeches in the modern era. A New York journalist close to Kennedy observed that the candidate “gave a talk that all his skilled speechwriters working together could not have surpassed.” John Lewis, a seasoned veteran of the civil rights movement who helped organize the rally, and today a congressman from Georgia, recalled that when Kennedy spoke the crowd hung on his every word. “It didn’t matter that he was white or rich or a Kennedy,” said Lewis. “At this moment he was just a human being, just like all of us, and he spoke that way.”

To help try and explain the tragedy, Kennedy recalled the words of Aeschylus, whose words from Agamemnon had comforted him following the assassination of his brother: “He [Aeschylus] once wrote: ‘Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.’” Kennedy went on to attempt to calm the crowd’s growing anger about King’s killing with these words:

“What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black. . . .

“We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times; we’ve had difficult times in the past; we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; it is not the end of disorder. . . .

“But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings who abide in our land.

“Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and to make gentle the life of this world.

“Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people.”

The news of King’s violent death at the hands of a white gunman had sparked outrage and violence across the country. Riots exploded in several cities, including the nation’s capital, Washington, DC. Regular army troops were called into action by President Johnson to bring the situation under control. But in Indianapolis, the crowd at Seventeenth and Broadway had taken Kennedy’s words to heart and had quietly left the rally and returned home. “We walked away in pain but not with a sense of revenge,” said Crawford.

Both whites and blacks who witnessed the Indianapolis speech described what they experienced in religious terms. Evans, the young high school student, said she has long held an “emotional memory” of Kennedy’s remarks and remembered feeling as if the candidate had “laid his hands upon the audience” and healed them, deflating the powerful anger that surged through the packed audience. “It was worth the wait,” she said.

Robinson believed that Kennedy’s speech and temperament changed the minds of those who were angry about King’s death. “I was thinking revenge right away,” Robinson remembered. “But then the words [Kennedy] used and his calmness made me understand the right response in the face of Dr. King’s assassination. His [Kennedy’s] speech made me reflect on what Dr. King stood for and that was peace and getting together and creating change. It made me realize one person could make a difference.”