Purchase Tickets

Romanos the Fencer and the Indianapolis Syrian Colony in 1906

April 6, 2021

“He has been the year’s one sensation on Willard Street,” wrote the Indianapolis News in 1906. “On Sunday mornings, Romanos, with long, white hair streaming over his shoulders, would get the young men of Willard street into the roadway. There he taught them the art of fencing and the entire colony gathered to watch him.”

Romanos was a gray-haired man, who like half a million Arabic-speaking people from Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, left his homeland to make a future in the New World before World War I. Perhaps 100,000 of these immigrants came to the United States, with a larger number going to Latin America.

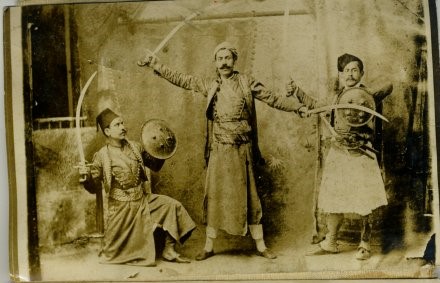

Romanos was not the only man among them with fencing skills. Swordsmanship was one of the many physical arts popular in the Ottoman Empire, which ruled the Eastern Mediterranean at the time.

U.S. impresarios recruited these fencers along with belly dancers and musicians to perform at vaudevilles, circuses, and fairs. One of the most famous examples was Boutros Holwey, who was featured at the Columbia Exposition of 1893, also called the Chicago World’s Fair.

Syrian fencers were often hired to perform as part of living exhibits at American fairs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Credit: Arab American National Museum, 2005.16.00

Fencing was loved and respected inside the Arab community as well.

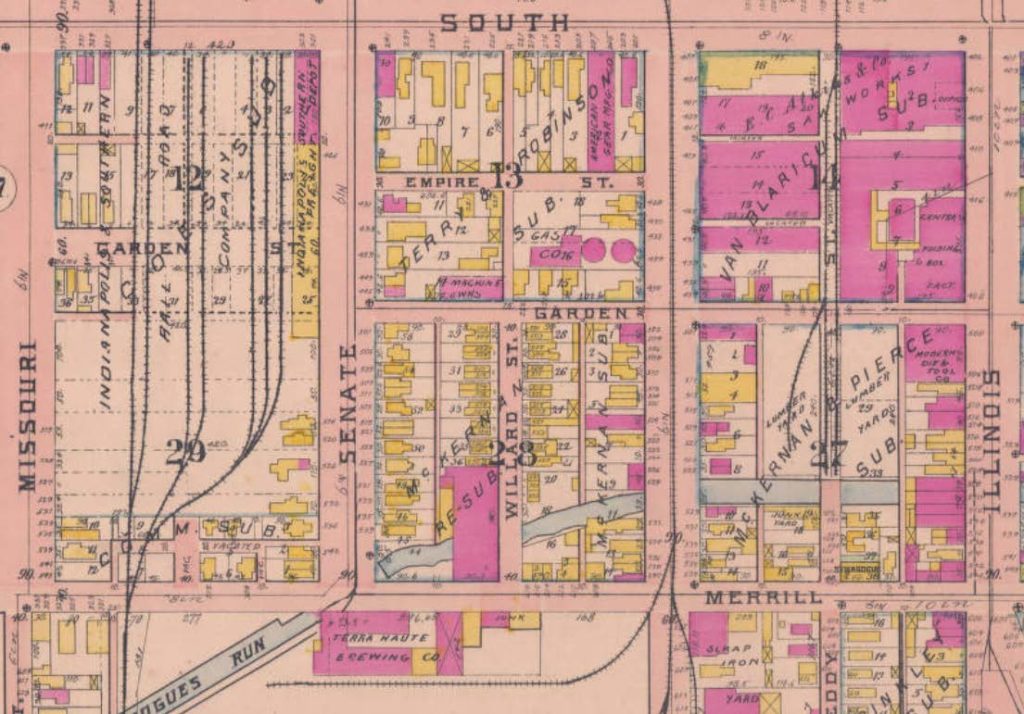

The Indianapolis News reported that Romanos “was a constant source of delight to all” who lived and worked on Indianapolis’ Willard Street, the Arabic-speaking neighborhood now buried underneath Lucas Oil Stadium.

Decades before the Indiana Ku Klux Klan led efforts to oppose the immigration of non-white people to the United States, immigrants from Ottoman Syria established Arabic-speaking neighborhoods in Terre Haute, Michigan City, Fort Wayne, and Indianapolis.

Indiana’s burgeoning industries needed cheap labor, and Syrians, along with 1.2 million other people mainly from Eastern and Southern Europe, immigrated to take up that work.

Some Hoosiers welcomed these immigrants. The Indianapolis News, for example, wrote about what it called the city’s “parade of nations,” and its coverage of Greeks, Jews, Hungarians, Romanians, and Syrians acknowledged their contributions and influence: “They give Indianapolis a cosmopolitan tone so varied in its hues that the city may be said to contain a collection of colonies gathered from almost every country of Europe into the heart of Indiana.”

By 1900, the U.S. Census counted about one hundred Arabic-speaking people in Indianapolis, but Indianapolis newspapers — the Journal, the News, and the Star — estimated that there actually two to three hundred of them. They found work in mills on the city’s south side, but became known to most people in Indianapolis as well as in Fort Wayne as peddlers, selling everything from needles and thread to silks from the Holy Land — “Oriental wears and bric-a-brac,” as the newspaper said. Many of these peddlers then became dry goods and grocery store owners.

This is why the man called Romanos had come to Indianapolis, too. His hope was to “sell fancy colors for candies, dyes of his own concoction.” Like other newcomers to the Syrian colony, Romanos was embraced by others from his homeland. It was not unusual for up to ten men and women to lodge in the narrow, “shot-gun” houses of Willard Street. Some were just passing through. Others did not yet have enough money to get their own place.

But Romanos was special. Not only was he an expert fencer, but he was also “a fine musician.” In the era before motion pictures and the phonograph provided popular entertainment, someone like Romanos was a special treasure. After arriving from New York, he was offered housing by other Syrians. In turn, “he made life merry for them.”

Pogue’s Run creek ran under the south end of the Willard Street, now the site of Lucas Oil Stadium. Credit: 1910 Baist Atlas

So, in early November, all anyone could talk about on Willard Street was the departure of Romanos. It came as a blow. “His sales here were not satisfactory,” the paper reported, “and one day three weeks ago, he left for Chicago, saying that he would go from there back to his old home in New York.”

He stayed such a short time that we are lucky to know anything about him at all. But remembering Romanos is a way of unearthing the contributions of Arabic-speaking Americans not only to contemporary Indiana but also to Indiana history.

Arabs are not new to the Hoosier state. They are as indigenous as most of its citizens. Recovering the Arab Hoosier past, too long ignored, is an important step forward in creating more accurate memories of who we really are, both yesterday and today.