Purchase Tickets

Pride Month: Newton Arvin, Valpo Native

June 18, 2024

In honor of Newton Arvin, I dedicate this blog to the struggles, both personal and community-wide in the LGBTQ+ population, and to celebrate this year’s Pride month. Arvin was a native of Valparaiso, Porter County, Indiana, identified above by the courthouse he would have passed during his younger years spent in Indiana.

Lately, I have given myself over to noting some fun month celebrations as designated by nationaldaycalendar.com. This month I have deferred that celebratory blog to my colleague, Cooper Davis, who will tell you all about our collection items related to National Dairy Month. However, blogs can’t always be about light-hearted topics, as much as I wish they could. And while history does include fun moments, it also accounts for trials and tribulations over time.

I recently conducted some research about Indiana authors. I was looking primarily for books authored by Hoosiers, and more specifically those also related to Indiana by topic or setting. I stumbled upon an Indiana author I was not familiar with, Newton Arvin. Arvin did not publish books about Indiana, but his formative years, from birth until age 17, and then at various times throughout his Harvard University years, were spent in Valparaiso. As quoted from his correspondence in Barry Werth’s The Scarlet Professor, Arvin did not have a fond connection with his hometown: “I don’t think I’ve ever hated this burg so as I have since I got back this time, I can’t imagine any atmosphere more oppressive than a small town like this.”

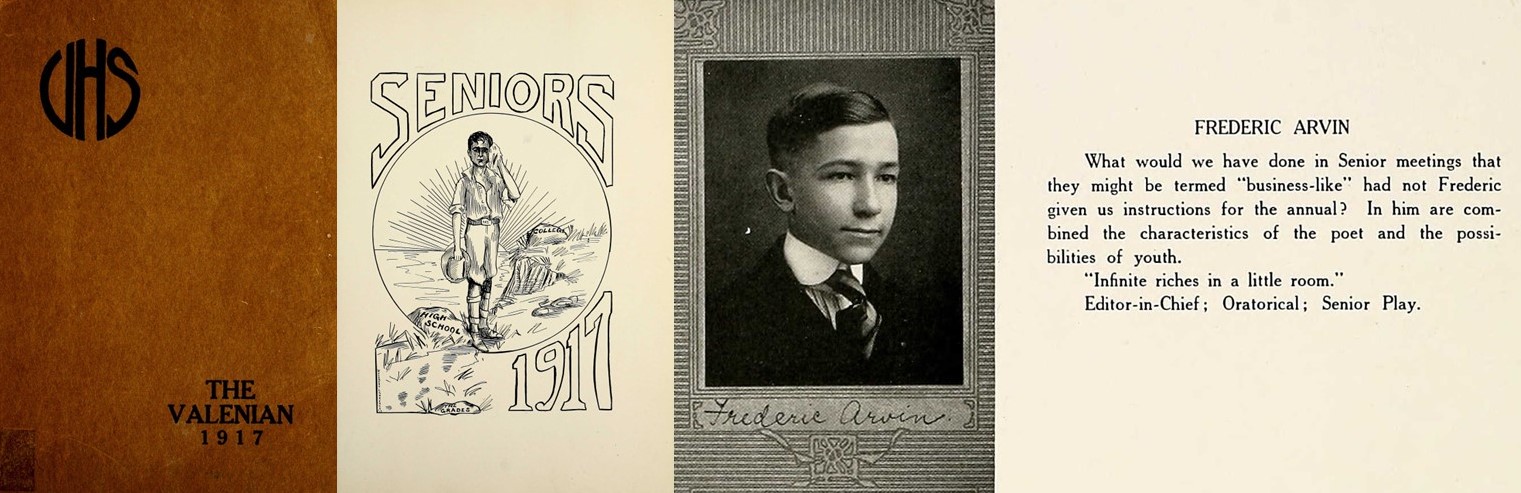

Selection of images from the 1917 Valparaiso High School Yearbook, The Valenian: Cover, Seniors page, Excerpted page showing Frederic Arvin (later known as Newton Arvin). Ancestry Library Edition, May 2024.

Arvin graduated from Harvard in 1921. Upon graduation, he taught at a day school in Detroit for one year, before accepting a position in the English Department at Smith College. Arvin was best known for his literary critique and biographies of authors such as Hawthorne, Whitman, Melville, and others. In 1932, he married Mary Garrison, a native of Connecticut, and his former student. The pair struggled with their relationship and divorced in 1940. Likely, one of the many reasons that his marriage to Garrison did not work, despite his wanting it to, was because of his true love: men.

Arvin, living in a time when it was not safe (or legal) to live as an openly gay man, was internally conflicted. Nonetheless, he had various documented relationships with men over time, which he noted in his correspondence and diaries. One of his most well-known relationships was a love affair with Truman Capote starting in 1946. Capote’s first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), was dedicated to Arvin, with whom he remained friends after their romance ended. Ultimately though, his identity as a gay man and sharing this part of himself with others would facilitate the end of his career.

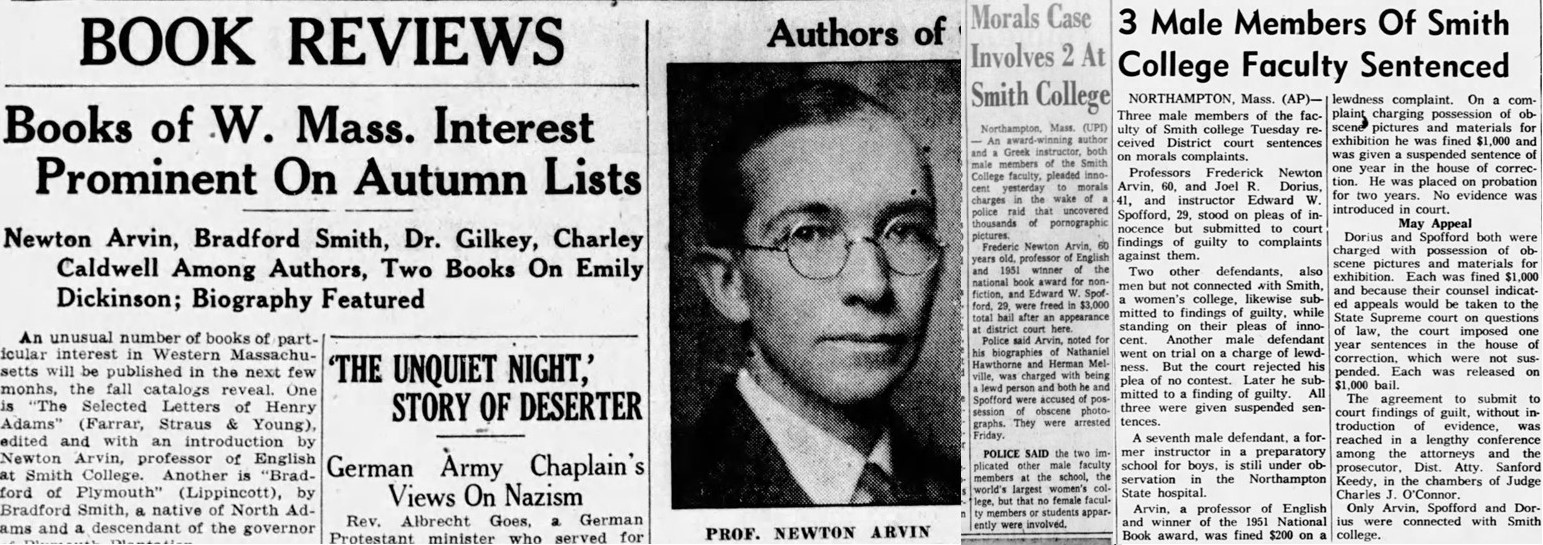

Newspaper articles about Arvin, one regarding Massachusetts interest books by Arvin and others, Morning Union, Springfield, MA, 26 August 1951, one from the arrest of Arvin and others, as appearing in the Indianapolis Star, 4 September 1960, one from the sentencing of Arvin and others, as appearing in the Richmond Palladium-Item, 20 September 1960. Accessed from Newspapers.com, June 2024.

The 1960s, while often thought of for the idea of “Free Love” which began in the latter part of the decade, early on, it did not always embrace those ideas. Much stricter and more rigid rules reigned, in a legal sense at least. Persecution of homosexuals was underway specifically in Northampton, MA, the location of Smith College, at the same time the US Postmaster General was cracking down on the sending materials deemed obscene, especially homoerotic imagery, through the US postal service. Possessing these to show to others was also a crime. In September 1960, Arvin and two of his colleagues were arrested and convicted of sharing these images with others, convictions that were eventually overturned, but not before the damage was done. All three lost their positions at the college. Afterwards, Arvin further struggled with his physical and mental health, which was already tenuous, and died just three years later of pancreatic cancer.

Digital images representing the IHS LGBTQ+ Collecting Initiative: Cover of The Works magazine featuring Nurse Safe Sexx, March 1986; Bat’n’Rouge Softball Fundraiser, 2010; Judge David J. Dryer, Marion County Superior Court, riding in Pride Parade, 2013. Bohr/Indy Pride/Gonzalez Collection, IHS; Mark A. Lee LGBT Photo Collection, IHS; Courtesy of NUVO, Mark A. Lee LGBT Photo Collection, IHS.

Join me in exploring more about Newton Arvin as I read Barry Werth’s The Scarlet Professor: Newton Arvin: A Literary Life Shattered by Scandal, coming to the IHS collection later this year. You can also explore other informative resources online at Smith University, on Wikipedia, GBLTQ.com an online “encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer culture and history,” and more. To learn more about images and items from the Indiana Historical Society’s LGBTQ+ collecting initiative visit our digital collection and library catalog.