Purchase Tickets

Pistol Packin’ Pastor: Part I

November 16, 2023

Figuratively speaking, the landscape of historical collections is strewn with Rabbit-Holes. Like Alice in Wonderland, if you choose one and jump down it, you never know when or where you’ll end up. Or who you’ll meet. As a processing archivist, I’m often the first to discover a particular hole and begin to map it out.

While processing a collection recently, I came across a number of photographs that seemed to have nothing to do with the rest of the material. Some of the people pictured were identified, so I set out to determine, if I could, how they were associated with the collection’s creator. This led me to the eventful life of Wilbur Ross Gibbons of Terre Haute.

The portrait of Gibbons (above) shows a young man in pince-nez spectacles, the typical high starched collar, and a well-tailored coat. He has a cleft chin, and his hair is carefully parted in the middle. The mat is signed, “Compliments of W. Ross Gibbons ’03.” I was grateful for that clue (seriously, please label your family photos!) because it allowed me to dig deeper. The photo seems to have been made for his 1903 graduation from DePauw University in Greencastle. A quick search for Gibbons in a newspaper database yielded some shocking results, including multiple instances of gunplay.

Shortly after the photo was taken, Gibbons met Rose J. Davidson, and less than a year later, in August 1904, the two were married. In late 1907, the couple joined a fraternal benefit society, and both were active in the local lodge. But trouble started a month or two later when a man named Edward Rosenrath joined the lodge and began to take an interest in Rose. “I saw Rosenrath take hold of my wife’s hand at different times,” Gibbons later complained, “And he would push himself against her and make vulgar motions at her bosom and other parts with his lodge sword during the drills.” But Rosenrath’s crude advances seemed to work. He and Rose began spending time together and Rose filed for divorce.

One night, Rose failed to show up to an arranged meeting with her husband to talk over their differences. Deflated, Gibbons headed downtown on his bicycle. On the way, he spotted Rose and Rosenrath walking together near a park. He confronted them. Gibbons and Rosenrath shouted blustery threats. Rosenrath teased Gibbons, “I got that woman to leave you and I got her to ask for a [divorce] from you.” Each accused the other of being a coward. “Don’t’ get funny,” Gibbons said. “You are a coward yourself and haven’t any more blood than a turnip.” Supposedly, Rosenrath “Picked up a piece of paving brick that was lying on the street” and moved toward Gibbons, saying “I’m going to kill [him].” Gibbons pulled out a .32 caliber revolver and fired three shots. Rosenrath, struck in the chest, was carried to the hospital (one paper reported that Gibbons helped), but he was pronounced dead. Gibbons surrendered at police headquarters.

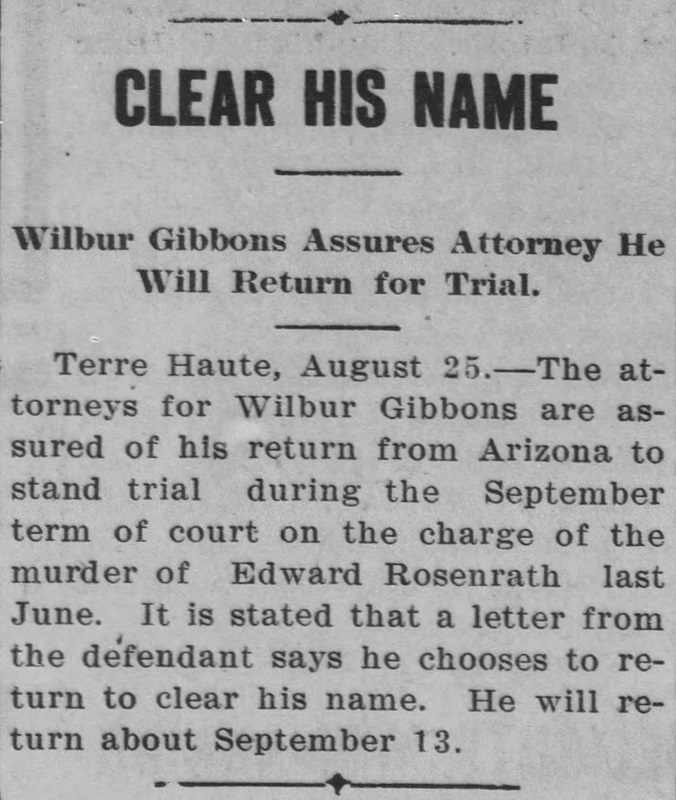

While awaiting trial, Gibbons was released on bond. He and Rose patched up their differences and escaped to Arizona where Gibbons had secured a position teaching on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation. He promised to return to Terre Haute to clear his name at his murder trial, which he did, in September of 1909. Thanks to several character witnesses (including Gibbons’ own mother) and Rose’s testimony that Rosenrath had indeed threatened her husband’s life, Gibbons was acquitted. Newspapers reported that the reconciled couple planned to return to Arizona.

Brazil (Ind.) Daily Times, 27 Sept. 1909

After the trial, the two remained married and in 1910 even welcomed a son. The family returned to Indiana, where Gibbons worked as a wheel finisher, perhaps in a wagon or carriage shop. But in a twist that nobody saw coming, in 1912 he applied for ordination in the Presbyterian Church.

Eventually, things between he and Rose got rocky, and in 1929, she again asked for a divorce. To say the least, the Rev. Gibbons reacted poorly.

The story continues in another blog post to be published soon.