Plan your visit

Ordinary Hoosier, Extraordinary Sacrifice

August 10, 2018

I grabbed a handful of Omaha Beach sand from the bucket and with a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes and rubbed the dark particles into the name on the cross.

Joseph M. Jordan, E Company, 506th Parachute Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, Indiana, June 6th, 1944

My student and I gently cleaned off the remaining sand and staked two flags – an American flag facing home and a French flag facing France. I laid a rose against the cross and stepped back to listen to Liam Hesting, a Columbia City High School junior, deliver the only eulogy ever given to PFC Jordan at the place of his burial.

It is a bit surreal to know that a 17-year-old and I are experts on this soldier from Muncie. Through an amazing opportunity from the Albert H. Small Normandy: Sacrifice for Freedom Student and Teacher Institute and National History Day, my student and I spent six months not only studying every aspect of the Normandy Invasion through readings and lectures from history professors at George Washington University, we also got to spend a week touring the battlegrounds in France. In addition, we were tasked with researching the life of this stranger – this “silent hero” – who died decades before either of us were born. Joseph M. Jordan started off as just a name on a list. By the end of our journey, he was a hero whose life and sacrifices I openly wept for.

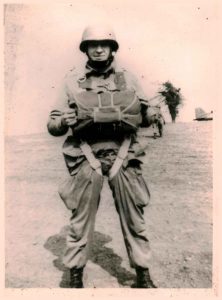

PFC Joseph M. Jordan, E Company, 506th PIR, 101st Airborne. Used with permission from the Carmichael Family

Getting to know PFC Jordan in order to write his eulogy took a great deal of research from both of us. We gained access to his military files from the National Archives, read biographies from fellow soldiers, stumbled into connections with family members who had photos and letters from Joe, and even tracked down Joe’s widow, Phyllis Jordan Pittenger, who lives in Florida. These puzzle pieces helped us put together a story of your average Hoosier who helped with the family farm, played basketball for Cowan High School, had a sweet tooth his mom often indulged and married his high school sweetheart.

Even after all these years, Phyllis Jordan Pittenger still mourns the loss of her first husband. Used with permission from Phyllis Jordan Pittenger.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Jordan volunteered for the paratroopers, trained for more than a year with the famed “Band of Brothers” preparing for this one day, a chance to begin the liberation of France. After surviving incredibly difficult training at Camp Toccoa and other camps around the states, a trans-Atlantic journey on an overcrowded troop ship, an emergency appendectomy in England, and final training maneuvers in the British countryside, D-Day had arrived. PFC Jordan jumped from a plane in the early hours of June 6 into enemy fire with the goal of securing a bridge and causeways to prevent German reinforcements from reaching the beaches as the Allies were landing. It was reported that Joe was shot helping free a fellow soldier from his parachute, one of more than 2,000 Allied soldiers who died that day, leaving behind his wife and newborn son, Joseph Theodore Jordan.

Joe told his wife that he loved jumping out of planes and was extremely proud to be a member of the 101st Airborne. Used with permission from the Carmichael Family.

Standing at Jordan’s grave was the culminating experience. Looking over the thousands of headstones at the American Cemetery, you can get lost in the numbers and forget that each cross represents a hero with a family, with a story. All of our work had led up to this moment, where this stranger now felt like family, and the loss felt very heavy on our hearts. It was personal now, and across the decades we could feel the sacrifice these men had made. That is why the Normandy Institute exists – so that people will learn, remember and teach others. We smiled and told Joe thank you. We told him goodbye and promised him that we’d tell his story.