Purchase Tickets

Losing the Vote, Winning the Election

February 15, 2019

History Matters is a blog series where we’ll be talking about the things you’re not supposed to discuss at the dinner table – things that may make some people uncomfortable. These pieces of our history are there if you look but might not be top of mind or in a textbook. We often think of history on a larger scale, but let’s remember that history happened here. It happens every day. And it matters.

From 1840 to 1940 almost 60 percent of the national elections had Indiana politicians on the ballot. Also, as an “October state” from 1851 through 1880, with elections for state and local officials held a month before the regular election, Indiana offered political parties a sounding board on the mood of voters. Party loyalty was expected of every man eligible to vote.

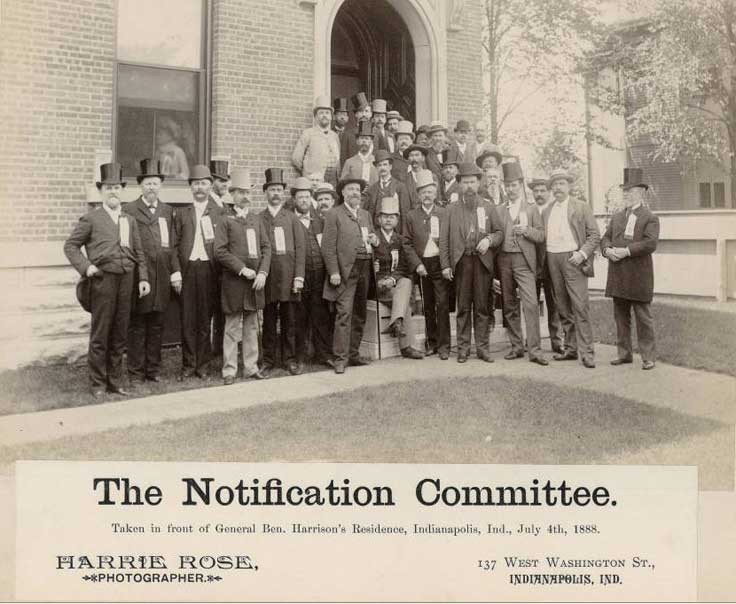

One day in 1888, the sound of marching feet echoed through the streets of Indianapolis. Armed with red, white, and blue parasols and led by drummers from 11 states, a crowd of approximately 40,000 commercial travelers marched up North Delaware Street to call upon Benjamin Harrison to notify him that he was the Republican candidate for president to run against incumbent Grover Cleveland. (Photo – Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site)

Winning states such as Indiana and New York could swing the election. Both Democrats and Republicans did all they could to corral voters for their candidates, including those known as “floaters” – people with no fixed party loyalties who often sold their votes to the highest bidder. The number of “floaters” in Indiana has been estimated to have been 10,000 in the 1880 presidential election and as high as 20,000 in 1888.

Party workers could buy these votes for as little as $2 or as high as $20 in tight contests, and since political parties, not the state, printed and furnished ballots to voters, could ensure that once a “floater” was bought, he stayed bought. “This infamous practice,” complained the Shelbyville Republican, “kept up year after year by both parties, has brought about a state of affairs that cannot be contemplated without a shudder.” The newspaper went on to lament that a third of the state’s voting population “can be directly influenced by the use of money on the day of election.”

At the beginning of the campaign, Harrison called for the two parties to “encamp upon the high plains of principle and not in the low swamps of personal defamation or detraction,” but his hopes were dashed when a letter from a Republican campaign official about the floating vote became one of the election’s greatest controversies. William W. Dudley, a Civil War veteran and the Republican National Committee treasurer, sent correspondence to an Indiana Republican county chairman warning that “only boodle and fraudulent votes and false counting of returns can beat us in the State.” To counter this threat, he advised Republican workers to find out which Democrats at the polls were responsible for bribing voters and steer committed Democratic supporters to them, thereby exhausting the opposition’s cash stockpile. The most damaging part of the letter appeared in a sentence where Dudley advised: “Divide the voters into blocks of five, and put a trusted man, with necessary funds, in charge of these five, and make them responsible that none get away.”

The political dynamite in Dudley’s letter found its way to the opposition thanks to a Democratic mail clerk on the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad who was suspicious about the large amount of mail passing from Republican headquarters to Indiana Republicans. He opened one of the letters, recognized its value to his party, and sent the damaging contents to the Indiana Democratic State Central Committee.

The Indianapolis Sentinel, a strong supporter of the Democratic Party, printed the letter on Oct. 31, 1888, under a banner headline reading: “The Plot to Buy Indiana.” Although an indignant Dudley and other top Republican officials declared that the letter was a forgery and denounced the person responsible for interfering with the mail, its contents received nationwide attention, with newspapers supporting the Democratic cause only more than happy to lambast Harrison for his ties to such chicanery, while Republican newspapers defended their candidate’s character.

What effect both the scandal had on the campaign’s outcome is still debated by historians. In his book on the 1888 election, Charles Calhoun argued that underhanded practices by both parties in New York and Indiana “may well have canceled each other out.” Cleveland’s supporters blamed bribery for costing their candidate New York and Indiana, which Harrison won by slim majorities. What isn’t generally talked about is, as Calhoun points out in his history of the election, the violent suppression of black voters in the South by Democrats – Cleveland swept all of the former slave states.

Harrison secured the presidency with 233 Electoral College votes. But in the popular vote, Cleveland bested Harrison, with 5,534,488 votes to 5,443,892 for his opponent, becoming the third of five presidential candidates to win the popular vote but lose in the Electoral College (the other losing candidates were Andrew Jackson in 1824, Samuel Tilden in 1876, Al Gore in 2000, and Hillary Clinton in 2016).

After the close election, in which 79.3 percent of the population eligible to vote went to the polls, Harrison seemed blissfully unaware that sleazy political shenanigans might have played a role in his rise to the presidency. He told Sen. Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, GOP national chairman, that “Providence has given us victory.” Quay, a veteran politician who considered the new president a “political tenderfoot,” was not moved by Harrison’s oratory. He later exclaimed to a Philadelphia journalist, “Think of the man! He ought to know that Providence hadn’t a damn thing to do with it.” Harrison, Quay said, “would never know how close a number of men were compelled to approach the gates of the penitentiary to make him president.”

Find out more

Benjamin Harrison: A Life, Ray E. Boomhower, IHS Press, 2019.

Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site Journey, Destination Indiana, IHS.