Purchase Tickets

Hot Off the Press – Two-Moon Journey

May 15, 2018

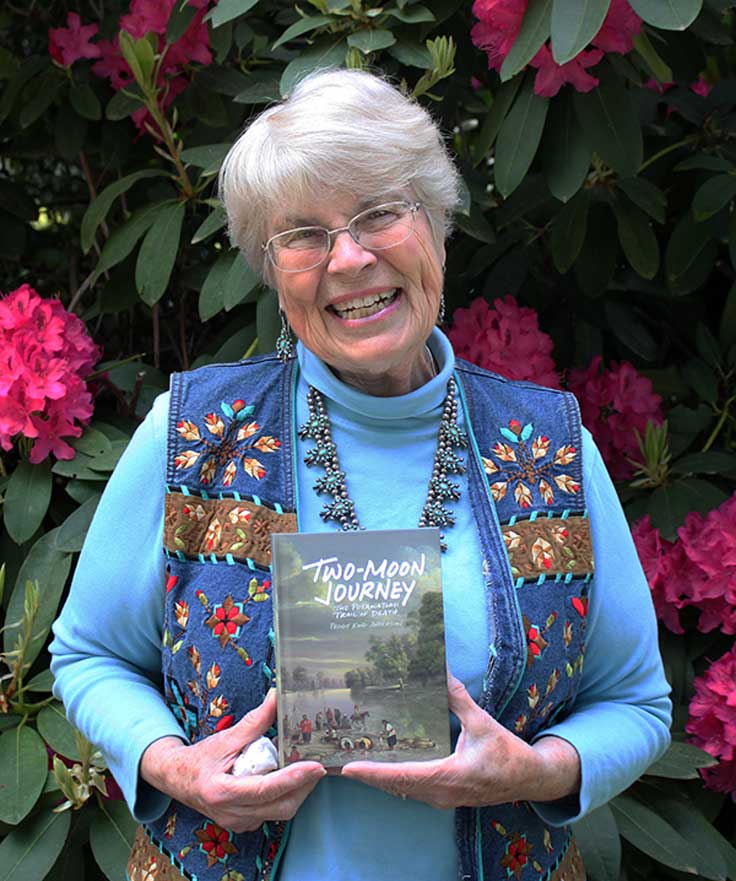

In our newest title for fourth through sixth graders – and beyond – author Peggy King Anderson tells the story of the Potawatomi removal from the perspective of young Simu-quah. Her story is full of tragedy but also of love and eventually forgiveness.

Peggy Anderson took the time to answer a few questions about her writing and the story. You can buy Two-Moon Journey: The Potawatomi Trail of Death at the Basile History Market in the History Center or online at shop.indianahistory.org.

What was your inspiration for Two-Moon Journey?

This book truly is a story of my heart! My husband, Ken Anderson, is part Potawatomi, and all of my five children are registered on the Potawatomi Tribal rolls. Years ago, our Potawatomi regional council representative, Susan Campbell, discovered I am a writer and encouraged me to write some of the stories of the People. I heard a lot about the Trail of Death, the forced removal of the Potawatomi from their homelands, and found myself drawn more and more into that powerful and sad story.

Then I met Virginia Pearl, a Potawatomi Catholic sister, whose great-grandmother had been 11 years old at the time of the Trail of Death. She told me the stories handed down to her, of this little girl who, at the end of that two-month (two-moon) journey, arrived with all her people in a November snowstorm in Sugar Creek, Kansas to find no shelter, none of the cabins promised them by the government. They had to hang animal skins along the bluffs of Sugar Creek to shelter from the freezing cold and snow. This one detail gave me an emotional “in” to the story I wanted to tell.

Who did you write this book for?

I can answer that in two totally different ways. I began writing the book for my husband and my children, to honor their heritage, and for all those dear Potawatomi who suffered so much from this Trail of Death, this journey so few really know about. But I also wrote the book for all those children and adults too, who don’t know at all about the Potawatomi Removal, what it was really like to be forcibly taken away from the only home you have ever known.

What was your research process for this book – sources and repositories?

Many of the facts and events of the Potawatomi journey are recorded in detail in three different diaries and journals. Fr. Benjamin Petit, who traveled with Simu-quah and their tribe in the story, was a real person. We know his story well, because he kept a journal during that time, documenting when he was with them at different stopping places on their journey, and what the conditions were like. He wrote long letters as well, to his family and church superiors, giving his account of parts of the journey: “I saw my poor Christians, under a burning noonday sun, amidst clouds of dust, marching in a line, surrounded by soldiers who were hurrying their steps. Next came the baggage wagons, in which numerous invalids, children, and women, too weak to walk, were crammed. They encamped half a mile from the town (Danville, Illinois) and in a short while I went among them. I found the camp just as you saw it, Monseigneur, at Logansport – a scene of desolation, with sick and dying people.” (From Fr. Petit’s letter recounting Sunday, Sept. 16th of the forced march.)

Two other people kept journals, recording this time and place: General John Tipton, who supervised the forced march to the Indiana state line, and Jesse C. Douglass, agent writing for William Polke, who supervised the remainder of the journey to Kansas. We have both of those original sources as well, and as I wrote the book, I was able to go back to these documents to allow Simu-quah to experience the real events of this hard journey.

During the research and writing process, did you find anything that surprised you?

Yes, I was surprised at how tenderly the Potawatomi people loved the young French priest, Fr. Pettit who accompanied them on the journey. It is so clear from his diaries and letters how he loved them, and they loved him. He respected and honored their Creation spirituality, and they honored this Jesus that Fr.Petit shared with them.

I was also delightfully surprised to hear Susan Campbell’s story of the special kind of chewy white corn her great-grandfather’s family brought on the journey, a corn her cousin’s family still grows and eats today, reminding them of the home they were forced to leave. Susan’s story fits in beautifully with the legend of the corn of forgiveness that I wanted to share in Two-Moon Journey. Surprising discoveries like these are one of the unexpected joys of writing!

I’m struck by the theme of forgiveness. How did that evolve and come up during your writing?

When Sister Virginia Pearl shared the vivid memories handed down to her by her mother and grandmother, the intensity of the suffering of the Potawatomi People on this forced journey became so real to me. That triggered a question that continued to nag me as I wrote: How could it ever be possible to forgive such a horrible injustice as what was done to the Potawatomi people, as well as all those other American Indians forced to leave their homelands?

In Two-Moon Journey, this conflict becomes personal as Simu-quah struggles with the hatred she has for the cruel red-bearded soldier who imprisons her father. Crider is a fictional character, based on the accounts of the cruelty of some of the militia who accompanied the Native Americans on this journey. Some were kind and showed compassion, but there were instances of cruelty as well, including Fr. Petit’s account of soldiers prodding with bayonets those who were not walking fast enough.

In the story, I used Simu-quah’s recurring dream, along with the legend of the Corn of Forgiveness to help Simu-quah find a way to confront her hatred of the soldier, Crider. Toward the end of the book, there is an accident and Simu-quah is faced with a terrible decision. Will she rescue the soldier who has been so cruel or will she allow him to die? As he lies wounded and close to death in a cave, he is in her power. In that cave, Simu-quah confronts not only the soldier but also herself and her hatred. As she makes her decision, Simu-quah finally understands the meaning of her recurring dream. She learns not only the Secret of the Corn but also the meaning of forgiveness.

You use quite a few Potawatomi phrases throughout the book. How did you come upon them?

The Citizen Band Potawatomi, of which my husband and children are members, has for many years emphasized regaining and retaining the Potawatomi language as an important part of our culture. I was able to access Potawatomi lessons online at the tribal site, and at different regional gatherings, we had lessons and handouts with Potawatomi words and expressions.

It felt important to me to share some Potawatomi language in the book because language is such an important part of who a people are, reflecting not only their culture but also their way of viewing the world.

Does Simu-quah’s name have a special meaning and where did the name come from?

Yes, Simu means a kind of little duck, and I came up with her name after talking with Susan Campbell, a dear Potawatomi friend who helped me immensely with this book. Because Chief Menominee’s clan lived by Twin Lakes, many of their names have water connotations. And in the Potawatomi tradition, kwa or quah is always a part of each female name.

Food, especially in the first couple chapters, is an important element. Where did you find names of dishes like blueberry dumplings and crooked corncakes?

That was one of the wonderful advantages of attending some of the Potawatomi feasts. Whenever the Potawatomi gather, there is always food! And the crooked corn cakes and blueberry dumplings really stuck in my mind. I drool, just thinking about them. There is also a Potawatomi cookbook, which is a wonderful resource.

And, unrelated to the book itself, what are you reading at the moment?

I am an eclectic reader and usually have at least three books at a time on my little reading table beside my recliner.

Right now I have The Great Alone by Kristin Hannah and America’s First Daughter by Stephanie Dray and Laura Kamoie. I’m also re-reading the journal I kept during my 2014 trip to Ireland with my daughter. Books I’ve read and loved recently include The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying by Nina Riggs, A Map of the World by Jane Hamilton, and Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward.

Anything you’d like to add?

I’d love to share the letter I got from my editor after I finished the book. It made me cry when I read it and speaks so clearly to my own hopes and dreams for this dear book, Two-Moon Journey. I share this letter with her permission.

Peggy,

We have so much to learn from our Native Americans if we will just listen. I hope that your book is picked up by schools across the country. I hope it engenders a lot of open conversations on the subject of the Indian removals. I hope the children ask “Why did these removals happen?” I know this is a lot to ask from one book of historical fiction for young readers. But, I think it is a reasonable hope if one thinks in the long term. … I will always be proud to have been a part of publishing this book!

Blessings to you,

Teresa

M. Teresa Baer

Managing Editor, Indiana Historical Society Press