Purchase Tickets

Gene Stratton-Porter: A Hoosier Renaissance Woman

January 29, 2024

I often wonder how the thoughts and perspectives of past writers would differ today. Gene Stratton-Porter (1863-1924) is one such writer, a popular novelist and environmentalist during the Golden Age of Indiana Literature alongside contemporaries like James Whitcomb Riley and Booth Tarkington. She was a Renaissance woman of the early twentieth century (before women even attained the right to vote), dabbling in photography and gardening in addition to her writing and environmentalism. As an outspoken naturalist, Stratton-Porter advocated for the preservation of Indiana’s Limberlost Swamp through her photography and stories. I can see her now, wading through bogs and swampland with her camera, photographing various bird species and their nests: cardinals, vultures, and — her favorite — owls.

The Limberlost Cabin, snow-laden, IHS, M1235.

I see a bit of myself in Gene Stratton-Porter. From 1895 to 1913, she lived with her family in what she fittingly titled “Limberlost Cabin” — now a historic site located in Geneva, Indiana — the name born from the property’s proximity to the swamp of the same name. Like Stratton-Porter, I live in rural Indiana, along the wooded banks of the Big Blue River. Although I’m not nearly as adventurous or outdoorsy as Gene, I frequently explored the woodland on my family’s property when I was a curious child (miraculously, I never returned home with a tick or two!). On occasion, I would spot wild turkeys, white-tailed deer, and even blue herons. Later, as I grew up, I developed a love for photographing wildflowers and all the gorgeous autumn foliage — though I lacked the fine wildlife photographer’s eye that Stratton-Porter possessed.

Original photographs, courtesy of yours truly.

As an aspiring author, I feel a deeper connection to Gene and her work. Throughout her celebrated career, she published twelve novels and two volumes of poetry. Her work characteristically contains lush descriptions of Indiana’s natural habitats (particularly the Limberlost Swamp), and her protagonists often find solace in nature and connect deeply with their green settings — much like the author. At one point in her career, Gene even negotiated with her publishers to publish one nature textbook for every work of fiction she submitted. Her books were enormously popular and still attract readers today.

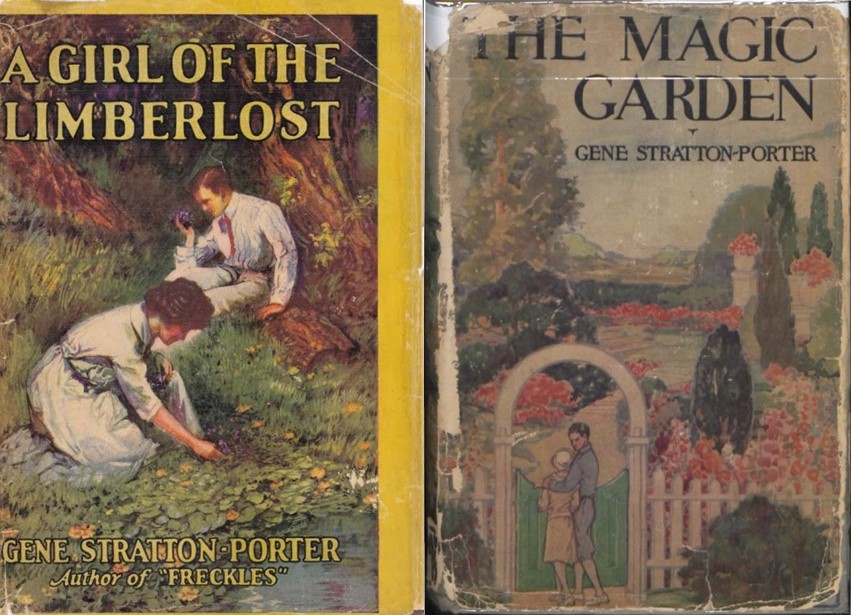

Stratton-Porter is hardly the first writer to glean inspiration from the natural world. The ultimate muse, Mother Nature, has influenced poets and prose writers since the dawn of the written word: odes to nightingales and Arcadia and paradise. But Stratton-Porter’s writing is unique in that she returned to her same local setting time and time again. The Limberlost Swamp and adjacent areas appear frequently in her fiction, from Freckles (1904) to A Girl of the Limberlost (1909) and other works. It’s apparent she loved her home!

I find it fascinating how these representations of rural Hoosier life and Indiana’s natural world have been little shared in literature since Stratton-Porter’s time. In fact, of the few contemporary Hoosier novels, the most popular are primarily set in (sub)urban Indiana. I hope that one day soon there is a renaissance of Indiana voices and literature, featuring the rural state at its best — perhaps one that rivals the “Golden Age” that Stratton-Porter helped to define more than a century ago. Today, her writing would likely look a little different, but I believe she would maintain her voice as an environmental advocate.

Gene Stratton-Porter’s career and success story proves that maybe, just maybe, I too can achieve success at writing novels about Hoosier life and Indiana’s natural beauty. With any luck, the new “Golden Age” could include me.

Come visit the Indiana Historical Society Library between now through March to view a small display about this fascinating Hoosier author. Later this year, from June through October 2024, you can see a larger exhibit on Gene Stratton-Porter in our 4th-floor gallery. To learn more, check out Gene Stratton-Porter and New Documents, Letters and Photos Round Out Gene Stratton-Porter Collection.