Plan your visit

County Extension Agents during World War II

September 20, 2024

In the Fall/Winter 2023 issue of Connections magazine, available through the IHS Member Login tab, Purdue University Extension specialist Frederick Whitford writes of the beginning of the Purdue Extension Agent program and the agents’ work through the Great Depression and World War II. The article is based on a book Whitford authored about the same topic, Planting the Seeds of Hope (Purdue University Press, 2023). There are so many interesting aspects of Extension history that Whitford could mention many of them only in passing. Two such aspects, which occurred during World War II, are narrated more fully below.

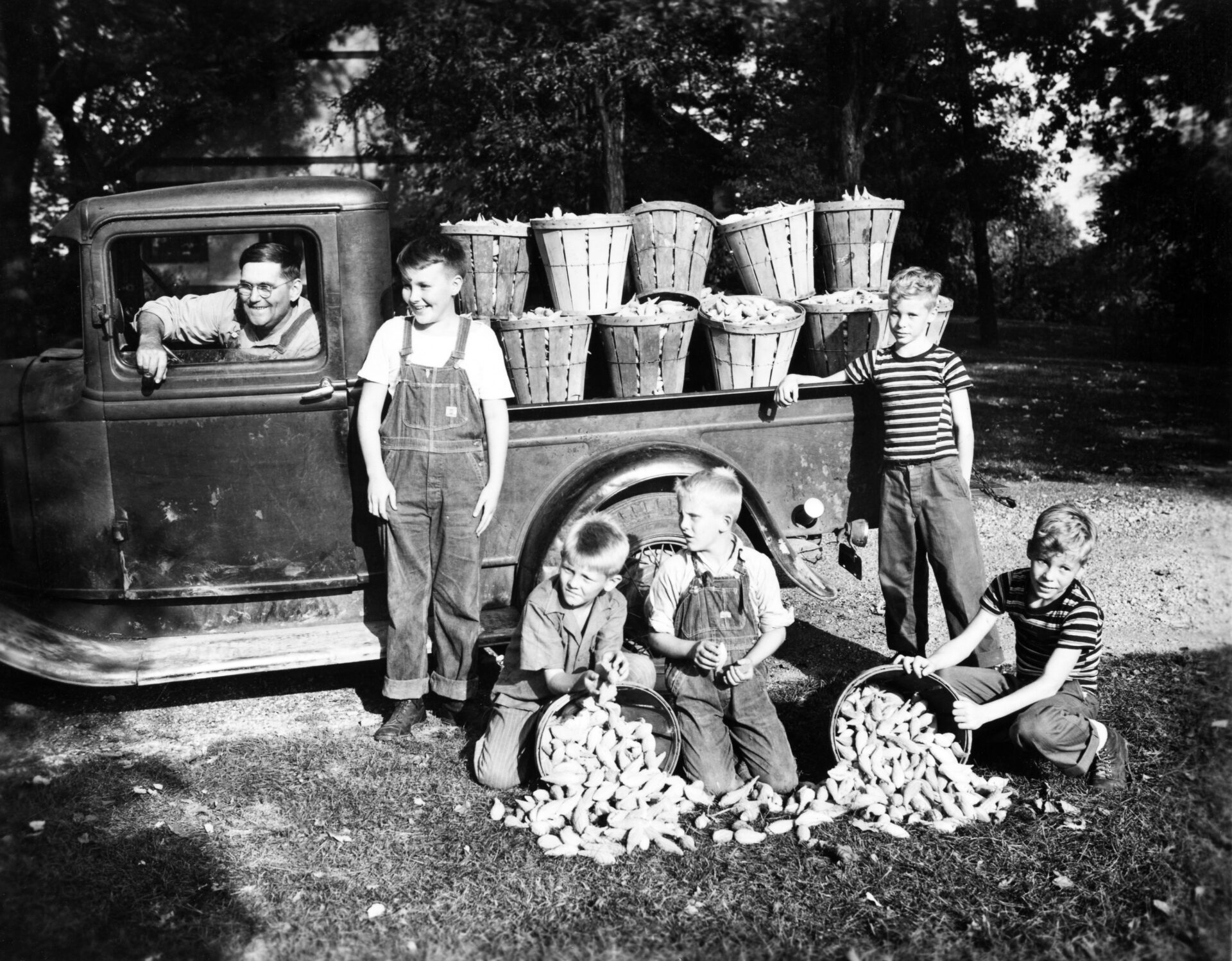

Schoolchildren of America Help Save Lives by Collecting Milkweed Pods

During World War II American sailors, soldiers, marines, and flight crews depended on life jackets, life preservers, rafts, and flight suits to stay afloat when enemy fire sank their ships or downed their planes over water. Those using such life-saving devices had a better chance of surviving in water until search-and-rescue operations could find them. Life jackets and similar equipment manufactured prior to World War II were filled with plant fibers processed from the fruit of the kapok tree. Early in the war, Japan established control in the one location in the world that supplied the United States with the vital fiber needed for military use. Scientists and inventors proposed a number of alternative fibers, but early on, the floss derived from milkweed pods topped the list due to what was already known about its physical properties.

By 1944 the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) asked each state where milkweed grew and designated a full-time director to spearhead a pod-collection program. Indiana’s assigned quota for 1944 was 10,000 bags of milkweed pods, with the size of the bags equal to the mesh ones used to hold fifty pounds of onions. The quota for Ripley County was 400 bags, while the Pike County quota was 1,000 bags. Each bag held 600 to 800 pods, which meant that volunteers would have to pick roughly 600,000 to 800,000 pods to fill their quota of 1,000 bags. The floss from one bag yielded roughly one bushel, or four-fifths of a pound of floss. It took one and a half pounds of floss—or approximately two bags of pods—to fill a single life jacket, so the floss from those 1,000 bags would be enough to pack approximately 500 life jackets.

The success of the statewide collection program hinged on getting student volunteers to harvest the pods in a timely fashion. Through newspaper articles and word-of-mouth promotions, agents made patriotic appeals to students, their parents, and the general public that collecting milkweed pods could save lives.

It was commonplace to see bags drying in barn lots, hung over fences, tied up in trees, or set on wooden frames. It took three to five weeks for the pods to dry completely. Pods that crackled when squeezed were dry enough to be moved inside the house, shed, or barn until the specified collection date. In the late fall, students were directed to bring the dried pods to their schools where they would be transported to Michigan to be processed.

The students’ work to collect milkweed pods should not be underestimated. While it will never be known how many lives they may have helped save, there is no doubt that gathering the pods produced the fiber needed to manufacture essential military equipment at a critical time. As a secondary benefit, through their participation, young people made a very positive and important contribution to the war effort.

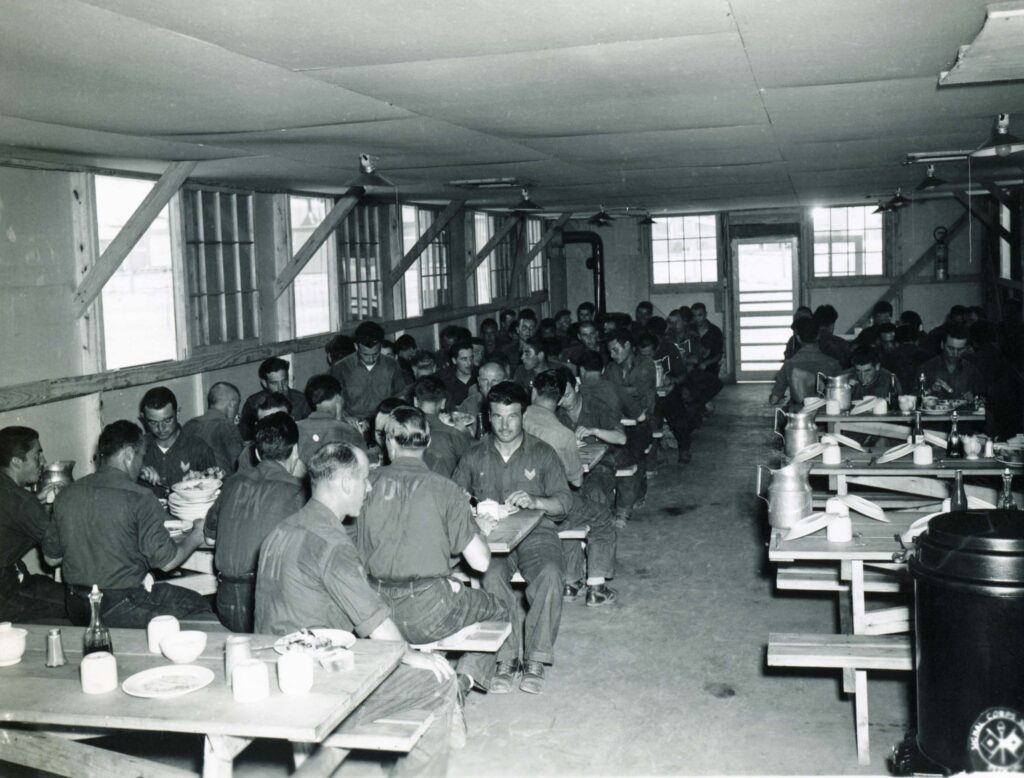

In 1943 approximately 3,000 Italian POWs were held at Camp Atterbury during World War II. Major Taylor Smith took this photo at Atterbury, circa 1943–46. Courtesy of Terry and Tevis McLaughlin.

German and Italian Prisoners of War Supply Labor on Indiana Farms

During the Second World War prisoners of war (POWs) were brought to the United States, beginning in April 1942, because the European prison camps were filled to capacity and the country needed labor to meet the demands of war. By the end of 1942, an estimated 30,000 POWs were arriving in the United States each month. Eventually there would be approximately 372,000 POWs from Germany, 50,000 from Italy, and 4,000 from Japan. By the conclusion of the war, half of the POWs in the United States had provided important agricultural labor.

There were 175 main camps and 511 smaller area camps for POWs scattered across 46 states. Indiana had three of the larger camps: Camp Atterbury at Edinburgh, Camp Thomas A. Scott at Fort Wayne, and Fort Benjamin Harrison at Indianapolis. Branch camps such as the one at Windfall, Indiana, housed 600 Germans from the Afrika Korps, who were captured in North Africa in 1943.

The United States abided by the convention relating to the treatment of prisoners of war that was signed at Geneva, Switzerland, on July 27, 1929, which spelled out principles regarding the humane treatment of POWs. Those held as captives could neither be forced to work against their wishes nor work in dangerous jobs. Therefore, prisoners were asked if they wanted to volunteer for assignments such as harvesting crops or working at a cannery.

Prisoners largely helped with harvesting crops, such as tomatoes, or working in the plants that processed them. In 1943 in Morgan County, POWs set, hoed, and picked tomatoes. That same year in Madison County, 800 German prisoners housed in a camp near Elwood worked in canning factories with American soldiers standing guard over them. Howard County employed some German POWs from the Windfall camp to pick tomatoes but hired more to work as tomato packers. In Shelby County, which had a branch camp located at Morristown, 400 POWs worked at 17 canning plants.

Prisoners of war in the chapel they built at Camp Atterbury, ca. 1943. For more information about the POWs and the detailed artwork created by them in their chapel, see the IHS Online Exhibit “Italian POWs at Atterbury.” Courtesy of Atterbury–Bakalar Air Museum, Columbus, Indiana.

The POWs did not work for free. According to Article 24 of the 1929 Geneva Convention, prisoners of war were to be paid based on prevailing wages. In Marion County, local farmers held a hearing to set the prevailing wage for POWs. Prisoners from Camp Scott at Fort Wayne were paid sixty cents an hour for detasseling corn and picking apples and peaches, and fifty cents an hour for other types of jobs, which were the same wages paid to non-POW farm laborers doing the same types of work.

The wages earned by the POWs were put into savings accounts, then given to each man at the end of the war. While in the camps, the POWs received scrip rather than cash from their earnings to spend on items at the camp. At the end of the war, POWs were repatriated to their home countries; all war prisoners held on U.S. soil were returned home by 1946.

[Bibliographic info: Enriching the Hoosier Farm Family: A Photo History of Indiana’s Early County Extension Agents, edited by Frederick Whitford, Neal Harmeyer, and David M. Hovde (Purdue University Press, 2016)]