Plan your visit

Pandemic History Lesson: Keep Calm and Carry On — Separately, In Your Own Homes

March 24, 2020

Once the first cases of COVID-19 left China, I gradually began stocking up on basic supplies. I knew it would end up here in Indianapolis eventually, and wanted to leave more diapers and toilet paper on the shelves for others once the panic-buying began. My husband and I also mentally prepared for the possibility of having our baby and our three year old at home with us 24/7 for at least a month. We would be quarantined on some level, that was for sure, and people would freak out.

I’m a public history librarian, and the spread of COVID-19 reminded me vividly of all that I knew about the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic: the media confusion; the governmental denials; the slow buildup in each community as leaders imposed restrictions that were too gentle, then suddenly admitted (way later than they should have) that more drastic quarantines were necessary. For an excellent synopsis of how Indianapolis coped with Spanish Flu, read this article from Jill Weiss Simins at the Indiana Historical Bureau.

The gist of it is that when dozens of cases began showing up at Fort Benjamin Harrison’s General Hospital, 25 in mid September of 1918, doctors insisted it was anything but Spanish Flu, and proclaimed that “an epidemic is not feared.” Take care of yourself and cover your mouth when you cough, advised public health officials, and everything will be fine. A few weeks later, according to Simins, “Indianapolis would be infected with over 6,000 cases with Fort Benjamin Harrison caring for over 3,000 patients in a 300 bed facility.” It wasn’t until October 7 that the city’s Board of Health banned public meetings and closed churches, schools, and theaters.

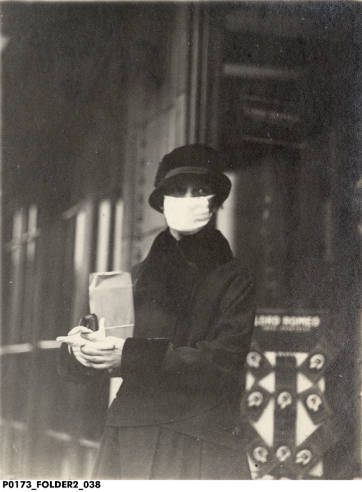

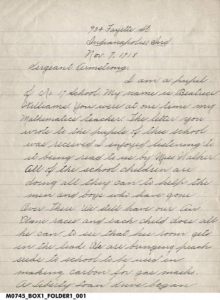

Unlike today, people appear to have taken the closures seriously and stayed away from each other. Perhaps several years of wartime collectivism helped, or maybe people had a keener sense of their own mortality at the tail end of the most destructive war the world had ever seen. Leisure activities ground to a halt. Stores that sold necessary goods took orders and placed packages on the sidewalk for customers to pick up. A November 7, 1918 letter in the Indiana Historical Society’s collection describes the weeks of protective measures. Beatrice Williams, a student at School #17, which served African-American students, wrote to Sergeant Irven Armstrong, who had been a teacher at the school before being sent overseas to France:

“There has been an epidemic of Influenza here and the schools, churches and all places of amusement were closed for four weeks. During the last week fewer cases were reported so everything opened again and we are back in school. I was a victim of the Influenza but I am alright now.”

So what will happen next? It depends how well people listen, and in the USA that’s a tall order. Getting Americans to follow instructions, or do anything inconvenient for the common good, is like herding cats. In 1918, in the end, 3,266 Hoosiers died from Spanish Flu. Though this was a lot, it was still a lower death rate than the national average. Why? Because—after a false start—the state offered sensible advice, and people listened.