Purchase Tickets

An April Fool’s Day Joke 96 Years Later

March 24, 2022

Recently I have been reprocessing the collection of Hugh D. Studabaker (1869-1943). Studabaker was a thorough diarist and completed exactly one diary page for every day of his adult life. On particularly eventful days, like the time he and his family attended the World’s Fair in St. Louis, Studabaker simply wrote smaller and filled the margins of the page. He never continued his entry on a second page. Studabaker also stuffed his diaries with all sorts of clippings, business cards, receipts, snapshots, pamphlets, and other detritus of daily life. In the process of sorting through all of this material, I came across more than a few surprises.

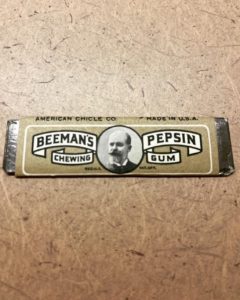

One particularly interesting item was a stick of Beeman’s Pepsin chewing gum, still in its foil and paper wrapper. This popular gum was first introduced around 1890. It’s been featured in movies like The Rocketeer, The Right Stuff and others. To find such a thing in an archival collection that’s been in our possession since the 1980s gave me a chuckle, and I sent my dad a text about it. I wondered if the gum could still be good. I also made a mental note to bring it up with our conservator, Stephanie Gowler. Foodstuffs and archival collections don’t usually mix, but I was interested to get her perspective. I continued going through the collection, and carefully placed the gum back into its folder until the following week.

Eventually, I had a chance to bring the gum to Stephanie in the conservation lab. I’ll let her describe what happened next:

“When Matt handed me the Beeman’s, my first impression was that it felt a little bit thinner and more rigid than regular sticks of gum. But then again, I’ve never had 100-year-old gum, and it certainly could have dried out and shrunk over time.

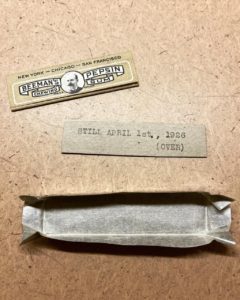

It was immediately apparent that the adhesive on the wrapper was no longer functioning, so I was able to carefully unwrap it without damage to see how the gum was holding up. I was already brainstorming potential storage options; food in collections can attract pests and potentially stick to adjacent materials, so we’d need to either remove the gum and just retain the wrapper or seal the entire thing in an inert plastic pouch.

However, the joke was on us, because once I lifted the first edge of the wrapper, we realized that it did not, in fact, contain a piece of Beeman’s but a gum-sized piece of cardboard with the words “STILL APRIL 1st, 1926 (OVER)” typewritten on it. And when I flipped it over, the same was typed on the back.”

I was completely surprised by the joke, and I’ll admit it took me a few minutes to wrap my head around what had happened. At first I thought perhaps this was something the Beeman’s company had done. But there’s no way for them to know when the gum would be unwrapped. Somebody Studabaker knew must have created the prank for Studabaker and perhaps other friends or co-workers.

Studabaker thought so much of the joke that he carefully re-assembled it and slipped it into his 1926 diary. I don’t think he could have ever expected that nearly 100 years later, the prank would be discovered by an archivist. But I have to say, it was indeed “still good.”

The Hugh D. Studabaker Diaries are available in our library as M0424.