Plan your visit

Finding Phillip Gomez, an Indianapolis World War I Veteran

December 3, 2024

Years ago, in a newspaper search I came across an article about a string of burglaries in 1931, one was at an Indianapolis chili parlor owned by Philip Gomez. Researching Phillip’s life has initiated multiple discoveries, and he has served as a teaching tool on of how we have statistically defined Latinos throughout history in Indiana and the United States.

Phillip was born as Felipe Gomez Jauregui on May 24, 1894, in Temacapulín, Jalisco, Mexico. He was one of three children born to Felix and Maria de Jesus Gomez. At some point he left Mexico and ended up Indianapolis, year is unknown. He first appeared in U.S. public records at the age of 21, when he married Martha (Mattie) Dunlap on May 23, 1916, in Indianapolis. Eight months later he is listed on the birth certificate for his daughter Marguerite Gomez, born on January 17, 1917. Months later in June, he enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War I.

Phillip’s life has been a teaching tool to illustrate the statistic invisibility Latinos faced in the early 20th century. Showcasing this as a common challenge towards this research. This invisibility is reflected in public records, such as the U.S. Census. During Phillip’s lifetime he would be racially categorize as white. However, after his marriage to Mattie, who was Black, would contribute to his statistical identity change on the U.S. Census. For the remainder of his life in Indianapolis, Phillip would be racially categorized as either negro, mulatto or colored. Their daughter Marguerite would be listed as mulatto. No photos of Mattie or Phillip is known to exist.

How, when, and where he met his wife Mattie is unknown. Also, what was largely unknown is where did he learned to cook and how he ended up in the chili (sometimes spelled chile) parlor business. Early public records of employment placed Phillip as a clerk or elevator operator at the Grand Leader, a local Indianapolis department store. There are periods of time where he was unaccounted for in annually recorded public records, like the city directory. Later, I would find the reason.

Before the chili parlor, he served during World War I, as was noted in his 1947 obituary. He served from 1917-1919 as a cook at Camp Sevier near Greenville, South Carolina. It was a training facility that trained over 100,000 soldiers. Soldiers that trained at this camp were from the 30th Division (known as Old Hickory), who deployed to France in the spring of 1918. Soon after, the 81st and 20th Divisions began to train at Camp Sevier. World War I would end on November 11, 1918, and Camp Sevier would be designated as a demobilized training center on December 3, 1918. It closed on April 8, 1919.

World War I Soldiers on a Train, 1919, W.H. Bass Photo Company Collection, IHS

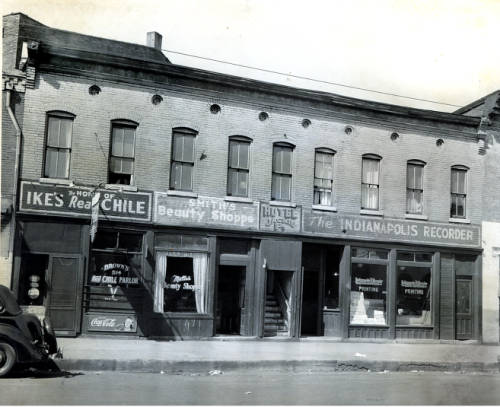

When he returned to his wife and daughter, chili parlors were popular establishments, and some dually served as saloons. He would be among many Mexican American men operating chili parlors in Indianapolis. Chili, itself originated in Mexico, first versions were recorded in the 1500s by Spanish Catholic missionaries in present-day Mexico. In the 1800s it was made by Vaqueros (Mexican Cowboys) who drove cattle in what is now known as the American Southwest, and the Texas “Chili Queens” who truly popularized this cheap-to-make and highly profitable dish on the Mexican border in the early 1900s.

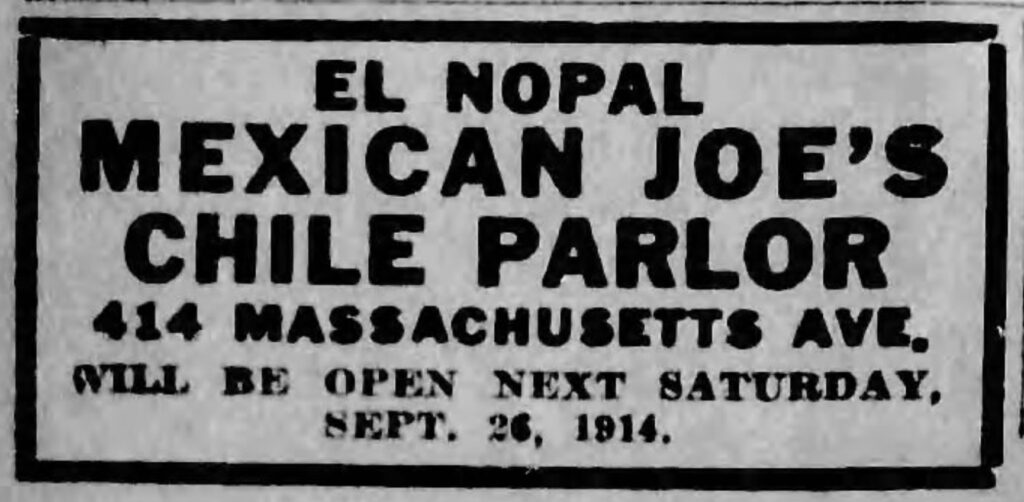

Mexican Joe’s Chile Parlor Advertisement, Indianapolis Star, September 26, 1914

Early Mexican Americans who operated chili parlors were recorded in Indianapolis as early as 1907. First with Thomas Garcia’s parlors, first on Capitol Avenue and later Indiana Avenue. In 1919 Indianapolis newspapers advertised “Genuine Mexican Chili” by non-Latino parlor owners. And several parlors over the decades had the popular name of “Mexican Joe.” Some were not Mexican or named Joe. There would be a few more identified Latino entrepreneurs in the early half of the 1900s, all would cash in on the popularity of Indy’s chili parlors, and tamales too.

Brown’s Real Chile Parlor on Indiana Avenue, 1948, Indianapolis Recorder Collection, IHS

Gomez’s restaurant opened sometime between 1927-1928 on 450 W. 11th Street (presently near the entrance to I-65). He did not publicly advertise, so the name of the chili parlor is unknown. And his parlor would disappear from public records between 1934-1935. Much is not known about his whereabouts until his death at age 52 in 1947. Phillip would pass away from the neurological disorder called Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. His obituary noted that he was buried in Crown Hill, but it was recently discovered that this Mexican-born, U.S. World War I Veteran was buried in an unmarked grave (no headstone).

Sadly, Phillip has no living relatives. His wife Martha (Mattie), never remarried and died in 1960. Their daughter Marguerite would earn a degree from Butler University, was a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, and Bethel A.M.E. church. She would marry Alexander Wills, never having children. Marguerite would also die young from cancer at age 53 in 1970.

The Attucks Yearbook, 1933, Crispus Attucks High School, Indianapolis, Indiana. Crispus Attucks Museum Collection, IU Indianapolis, University Library Digital Collection

With no living relatives, I put in a request for his military records at the National Personnel Records Center (St. Louis, MO). Archivists know that in 1973, the records center suffered a devastating fire that destroyed 16-18 million official military personnel files, that included 80% of military discharge records from 1912-1960. I filed a request, not hopeful that his records would be one of the few that survived. While they did not have his discharge records, they found his “Final Pay Statement”, a financial document issued by the War Department and was given at discharge, listing their itemized final payout. This is a financial document and not an official military discharge document.

The back of the document had lengthy remarks that gave me insight into his service. He held the grade of cook from 1917-1918, and his “expiration of term of service” was in 1919, likely after Camp Sevier was officially shut down. He was discharged with the title of Private at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indianapolis. However, within that time there were short periods of where he was absent without leave (AWOL), where a portion of his pay was automatically docked. However, he was awarded his veteran’s bonus.

Lack of official military discharge documents and no living relatives may be the underlying reason as to why he does not have a headstone. At the time of death, veterans who are eligible for their benefits receive a financial allotment for funeral and burial costs.

Today, almost 80 years later, Phillip Gomez, a Mexican-born, U.S. World War I Veteran and Indianapolis restaurant entrepreneur, continues to rest at Crown Hill cemetery in an unmarked grave.

To learn more about Indianapolis Latino-operated chili parlor history, read here.