Plan your visit

Discovering Notre Dame’s Latin American Students, est. 1851

April 8, 2024

In 2021 I wrote about the history of Cinco de Mayo in the United States which led to my discovery of the first documented celebration in Indiana in the early 20th Century, decades before the American commercial popularization of this holiday that we all know of today.

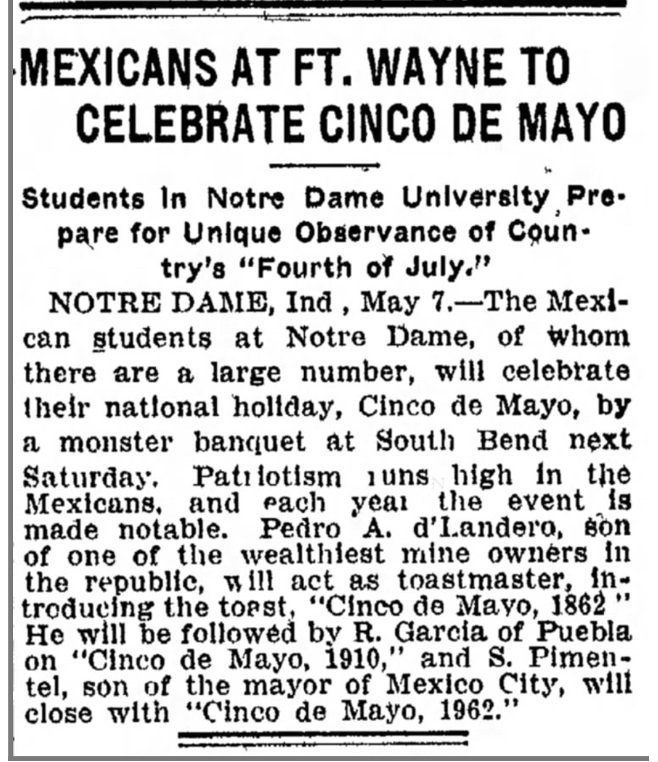

On May 9, 1910 the Indianapolis Star published an article with the splashy title, “Mexicans at Ft. Wayne to Celebrate Cinco de Mayo; Students in Notre Dame University Prepare for Unique Observance of Country’s ‘Fourth of July.’ ” Mexican students attending the University of Notre Dame were to hold a “monster banquet” on the following Saturday. Student leaders of this event were Pedro A. D’Landero (De Landero) of Guadalajara, R. Garcia of Puebla, and S. Pimentel of Mexico City. It noted that this tradition had been held in previous years. Researching for other public mentions of this holiday and more about its origins led me to uncover the history of Latin American students at Notre Dame. While I assumed that these three students from 1910, who came from prominent families in Mexico, were some of the first to attend this university, I soon found that my assumption was off… by almost 60 years.

1851-1883 The First Latino Students:

Notre Dame was founded in 1842, and chartered in 1844. From 1850-1883, Latin American students and cultural studies were a part of its curriculum before 1900. The first Latin American student on record per their annual announcement was William Smith of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico in 1851. No further mention of him afterward. In 1854 Spanish language classes were offered as an elective and in 1859 Spanish Literature was added to course offerings. Latin American students would trickle in: 1862 Edward Dunbar of Havana, Cuba; 1868, John Wilson from “Aspinwall, South America” (Colón, Panama); 1876 Thomas Logan of “Chili” (Chile), South America. However, in 1864 Mexican American students, Alejandro, Juan, and Elias Perea from New Mexico entered Notre Dame. The March 2,1872 issue of the Notre Dame Scholastic noted more student arrivals from New Mexico and Texas. Anecdotally, it also made mention of “Mexican Ponies” at neighboring St. Mary’s Academy (St. Mary’s College).

More than likely the Perea brothers’ parents were born as citizens of Mexico. Per the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 that ended the Mexican American War, Mexico had to cede 55% of its northern territory. This made native-born Mexicans citizens of the southwest of the United States overnight. Notre Dame school catalogs were translated into Spanish, to entice wealthy families of Latin America to send their sons to the American Midwest. This effort would pay off in1883, when the university saw its largest Latino student body, accounting for roughly 7.5% of the total student population. Mostly they were Mexican and Mexican-American men.

The “Little Ones”

Not all students at Notre Dame were of college age. The university also had a boarding school for school age boys, some as young as 5. Some would spend the entirety of their formative years in South Bend, Indiana. They were referred to as “Minims”, French for “little ones”. In the 1903-1904 academic year catalog there were six Latino Minims who hailed from Cuba, Mexico, New Mexico, and Peru. The practice of admitting Minims ended in 1929.

Latinos of the 20th Century: Professors, Trustee, and Cultural Clubs

The momentum of diversity continued into the 20th Century. Beyond students, in 1883 they conferred an honorary degree to Luis Terrazas, the mayor of Chihuahua, Mexico. By the turn of the 21st century, this became more evident with the appointment of Latino faculty and trustees, all of whom were alumni. In 1906, Benjamin R. Enriquez (Class of 1904) of Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico was a Professor of Mathematics and Gustave L. Trevino (Class of 1908) of Monterrey, Nuevo, Leon, Mexico served as a university trustee from 1909-1911.

More students from Europe, Latin America and the Philippines had an increased presence on campus. Student diversity was depicted in the yearbook with cultural clubs. The 1906-1907 yearbook lists twenty-four members of the Latin Club of Mexico; nine members of the Columbian Club of South America; and thirteen members of the Philippine Government Student Club. All would have been initially influenced by Notre Dame’s Spanish language catalogs. Latino students also belonged to several other non-cultural clubs, such as the Aero Club, Boat Club, Civil Engineering Society and Electrical Engineering Society.

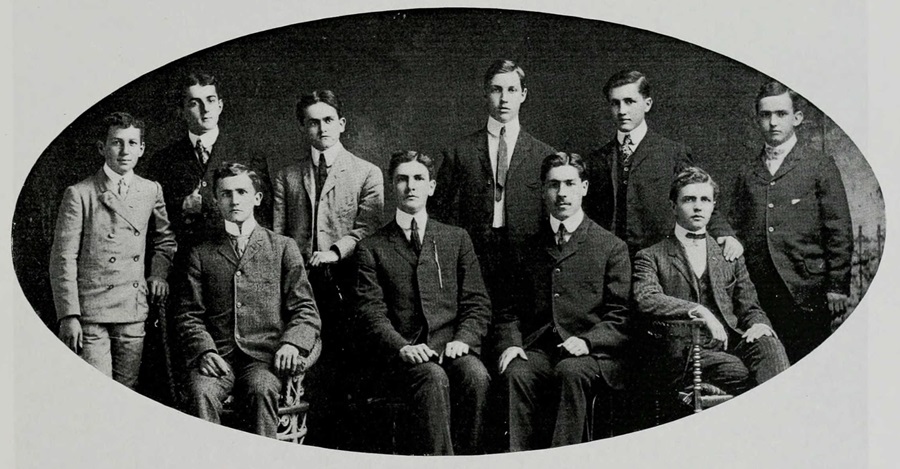

Columbian Club of South America, 1906. The Dome Yearbook, University of Notre Dame. (Accessed via Ancestry.com)

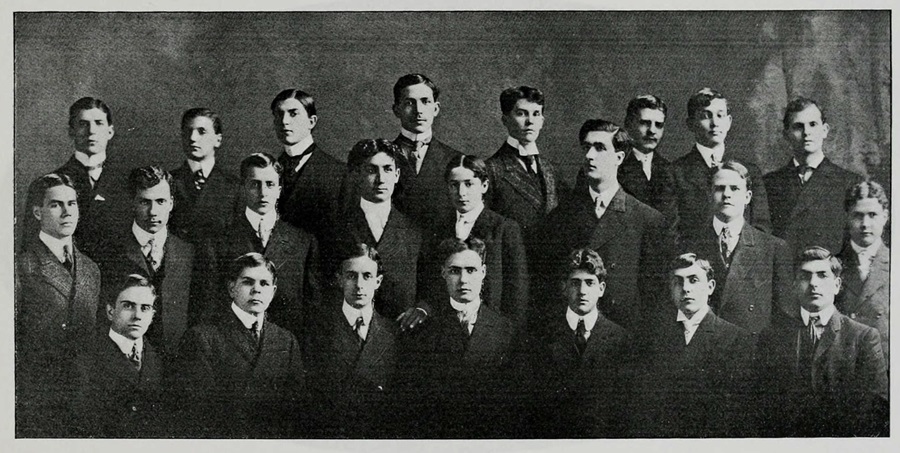

The Latin Club of Mexico, 1906. The Dome Yearbook, University of Notre Dame (Accessed via Ancestry.com)

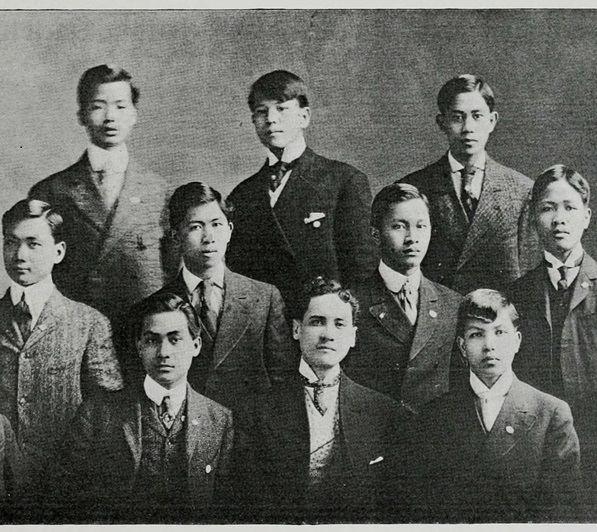

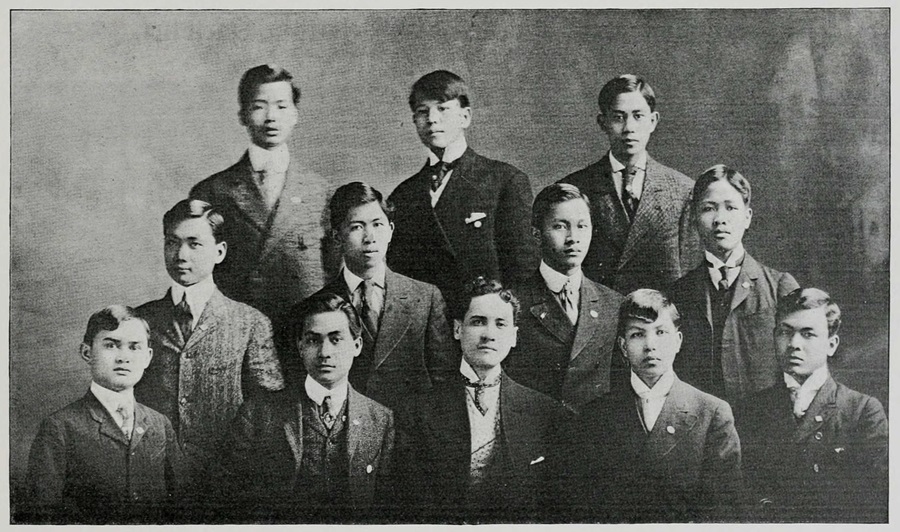

Philippine Government Student Club, 1906. The Dome Yearbook, University of Notre Dame (Accessed via Ancestry.com)

It is likely that members of the Latin Club of Mexico began the inaugural celebration of Cinco de Mayo in Indiana, with the 1910 Cinco de Mayo banquet as the first publicly documented celebration in state history.

Indianapolis Star, May 9, 1910

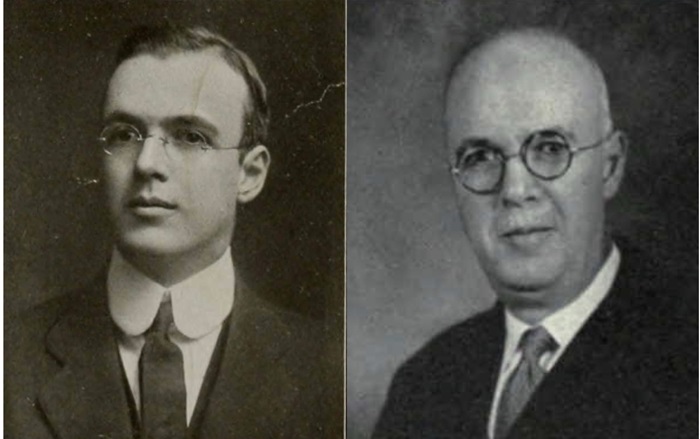

One of the students, the toastmaster of the 1910 ceremony, Pedro A. D’Landero (De Landero) followed in Benjamin Enriquez’s footprints, becoming a professor at Notre Dame in the 1929-1930 school year. Who was Pedro? He was born in 1889 as Pedro Antonio De Landero y Weber in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. Both of his parents were native to Mexico, the last name “Weber” came his maternal great grandparents, Eduard Weber and Julia Herter. Eduard and Julia were German immigrants who emigrated to Mexico. Eduard was involved in the mining industry and Pedro’s family were mine owners, most likely precious metals. Pedro’s 1911 yearbook described him being nicknamed “Pete”, “Olla” (Mexican ceramic cooking jar), or “Dinamita”(dynamite) by his friends. He was 6ft tall and was best friends with University President, Fr. Lavin. After college he did return to Guadalajara, married in 1913, and had two sons in 1915 and 1916. While the children were in middle school, Pedro returned to Notre Dame as a Spanish professor, later his two sons attended their father’s alma mater. Pedro and family returned to Mexico after their youngest son’s graduation in the late 1930s. Pedro passed away in Mexico City in 1943, at the age of 54.

Pedro A. De Landero, 1911 and 1930, The Dome Yearbook, University of Notre Dame (Accessed via Ancestry.com)

This was such a rich and pleasant discovery, proving once again, that Latino History in Indiana goes farther than one would assume.

Special thanks to Angela Kindig at the University Notre Dame Archives.