Plan your visit

From Shortridge High School to Vietnam

March 11, 2024

Raised in Indianapolis, Indiana, by his mother, Nancy, and stepfather, Frederick G. Schatz — whose interracial marriage had shocked both the city’s Black and white communities — Wallace H. Terry was urged by his stepfather to rise above the racism he faced daily in his hometown, where African Americans could not sit down and eat with white customers in local restaurants, register as guests in downtown hotels, or swim in public pools.

The youngster discovered, however, that he was always welcome at the city’s public library, Terry walked up two flights of marble stairs to the main reading room. When he looked up, he could trace the early history of the state through a series of bas-relief plaster plaques.

One eventful day, Terry asked a librarian for her recommendation about a new book to read. He remembered that she thrust into his hands a book with what he considered “an unpronounceable title — The Iliad, the Greek epic poem by Homer.

Baffled about what he had been given, Terry felt some relief when the librarian told him: “Wally, don’t worry. It’s a word you can learn like any other words. And as you make your way through these pages, if you have trouble with other words, I’ll help you to the dictionary and we’ll see how we can work our way out of it.” He recalled that he began to realize that he had in his hands a book about war with a “very important message.”

A few years later, as a student at Shortridge High School, the state’s oldest free public high school, enrolled in the fourth-year Latin class taught by Josephine Bliss, he was introduced to another book about war, Virgil’s The Aeneid. Burned into his brain were its opening lines: “Arms and the man I sing, who, forced by fate / And haughty Juno’s unrelenting hate, / Expelled and exiled, left the Trojan shore.” Terry began to wonder if perhaps someday he could write a book.

Terry graduated from Shortridge in 1955. Applying to several colleges, he picked Brown University, an Ivy League institution in Providence, Rhode Island. Visiting the Daily Herald’s offices during its freshman recruitment period, Terry announced to the newspaper’s staff that he would one day be its editor. Reflecting on his boldness, he said it delayed his admission to the newspaper’s staff. “I had to heel longer than anyone in history just to cool me down,” said Terry. He eventually became a reporter and the first Black to serve as the Daily Herald’s editor-in-chief. Before his senior year, Terry worked at the Washington Post, where he “was treated like a regular reporter [and] paid union scale. That was phenomenal because I was only nineteen when they offered me the job.”

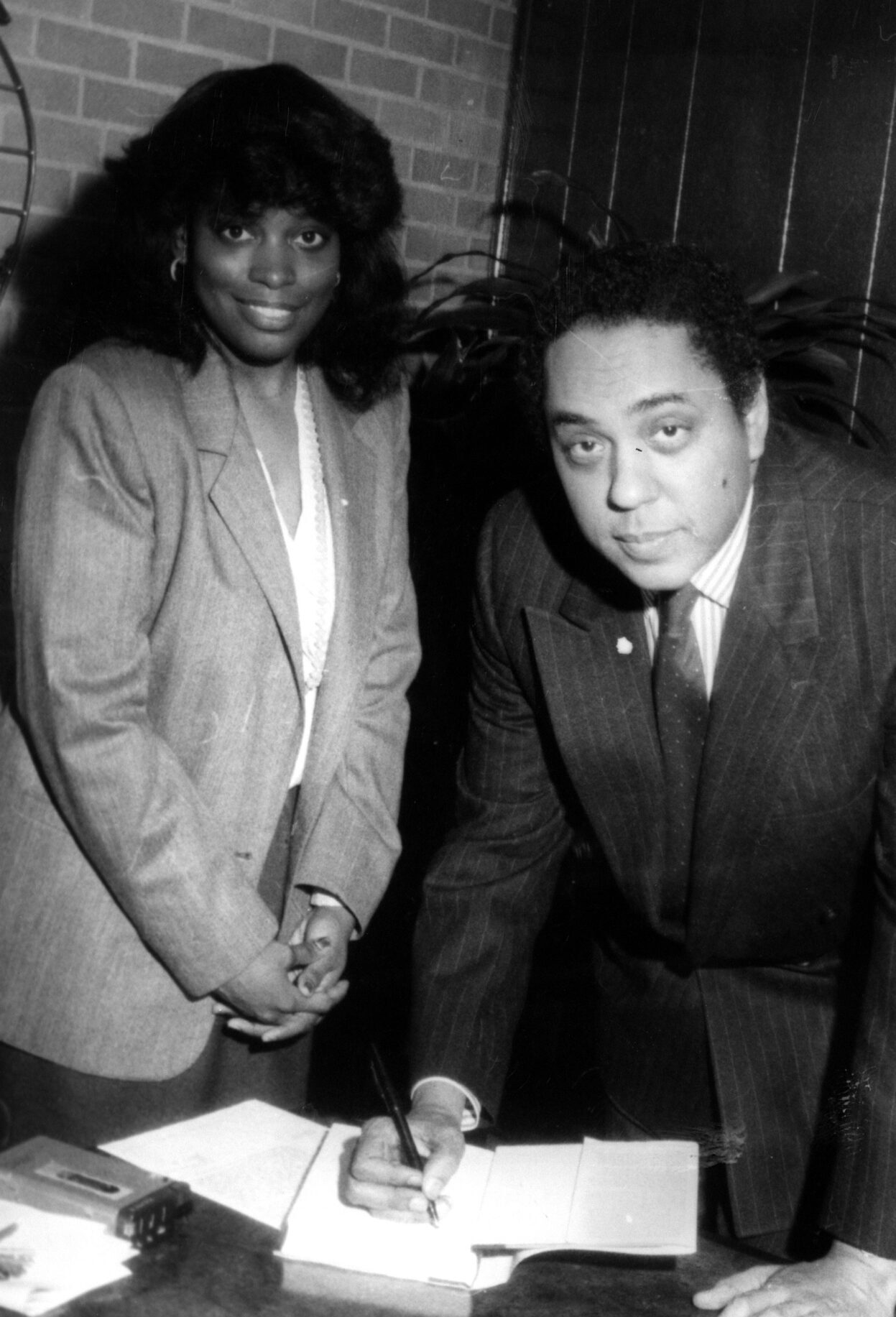

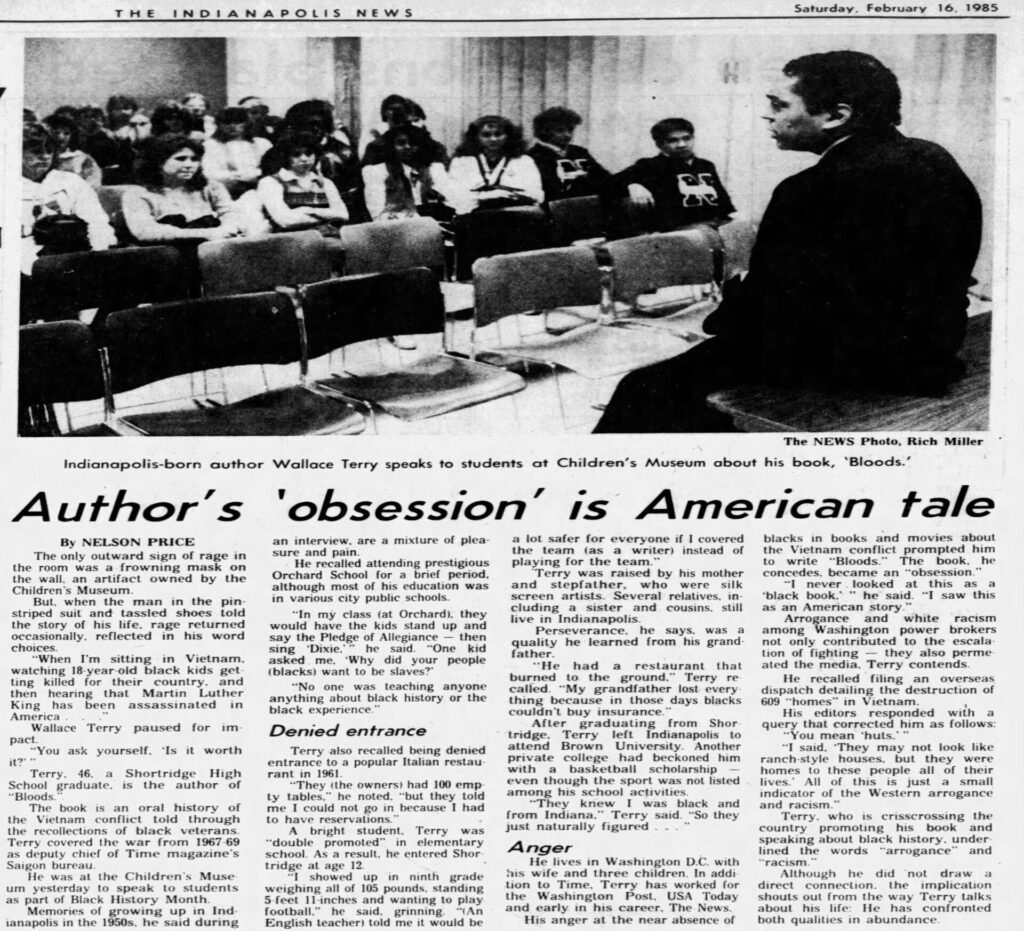

After the publication of Bloods, Terry embarked on an ambitious national tour in which he spoke to young people about his experiences during the Vietnam War. Here he speaks to students gathered at Indianapolis’s Children’s Museum in February 1985. Newspapers.com

After graduating from Brown in 1959, Terry received a Rockefeller theological fellowship to the University of Chicago and became an ordained minister with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). He missed journalism, however, and sought a part-time job in the field. Terry received career advice from Fletcher Martin, a Chicago Sun-Times reporter and the first Black to win a prestigious Nieman Fellowship at Harvard, an honor Terry later received. Learning that Terry had worked the previous summer for the Post, Martin told him: “Son, it took me twenty years to get where you got to before you even got out of college. You don’t need to talk to me. You need to go back to the Washington Post.” Martin called Al Friendly, the Post’s managing editor, asking him to hire Terry; Friendly did.

After about a year with the newspaper, Terry became deeply involved in covering the civil rights movement. “To me it was the biggest story in the country. It was a story that I passionately cared for because it was going to affect me, my family, my children, and generations of black people to come,” he noted. He did a series of articles about the Nation of Islam, interacting with a charismatic minister named Malcolm X, as well as writing about protest marches in the South. Terry continued to cover the struggle for civil rights after moving from the Post to Time magazine, at the time the country’s top news magazine.

Terry had his first opportunity for an overseas assignment in early 1967 when he suggested that the magazine do a cover article about Black soldiers fighting in Vietnam. Richard Clurman, Time’s chief of correspondents, called Terry to ask him to fly to Vietnam to help with the story. Terry accepted the assignment, believing that the attention President Lyndon Johnson had given to civil rights and his Great Society programs had been overtaken by a fixation about Vietnam. The piece, which ran in the magazine’s May 26, 1967, issue, pointed out that for the first time in the country’s history, Black soldiers were “fully integrated in combat, fruitfully employed in positions of leadership, and fiercely proud of their performance.”

Impressed by Terry’s work, Clurman asked him to return to Vietnam for a two-year stint in Time’s Saigon bureau, working as its deputy chief. Terry quickly accepted the assignment, as Vietnam represented “the biggest story in the world.” Also, in the back of his mind, he thought he could write a book about his experiences. “Maybe I got a rush from the danger and from the excitement,” Terry said years after his overseas assignment ended. “I went to where the action was because I felt that’s the only way I could fully tell the story.”

Terry learned that racial relations among American troops in Vietnam had deteriorated from the hopeful story Time had published just a year before. After traveling all over the country, from the demilitarized zone to the Mekong Delta, interviewing American forces, Terry saw that the gung-ho professional soldiers who had volunteered for service early in the war had been superseded by draftees who were much more cynical. “Replacing the careerists were black draftees, many just steps removed from marching in the Civil Rights Movement or rioting in the rebellions that swept the urban ghettos from Harlem to Watts,” Terry observed. “All were filled with a new sense of black pride and purpose.”

Terry set out to use the information he had gleaned in notebooks and tape cassettes to produce a book about the war, leaving his job at Time to do so. As he sorted through the material and wrote, Terry supported his family by serving as a consultant to the U.S. Air Force, teaching journalism at Howard, and working for an advertising agency. Terry, however, could not find anyone willing to publish his work. Many publishers rejected his manuscript because, he recalled them telling him, Americans did not “want to hear any more about Vietnam. They most certainly do not want to hear anything connected to blacks who were in Vietnam.”

Finally, in 1982, Random House expressed interest in his work. Erroll McDonald, an editor at the publisher, however, suggested that instead of a narrative the book should be done as an oral history. Author and broadcaster Studs Terkel had experienced great success with his oral history collections, including Hard Times (1970) and Working (1974).

From a list of 50 possible subjects, he featured twenty in Bloods, with the common thread among them being they were Black veterans talking about what they had faced during the war and after. Bloods achieved for Terry what he had set out to accomplish, eventually serving as the basis for a program by the PBS television series Frontline and adapted for the National Public Radio program “All Things Considered.”

The shadow of the Vietnam War continued to loom large in Terry’s life until his death on May 29, 2003, from a rare, undiagnosed vascular disease. He compared the conflict to the U.S. Civil War, seeing it as a subject Americans would “go back to and back to and back to. We’ll never get away from it.” It was a war he believed could not be romanticized, seeing it as “too ambiguous. But we’ll be writing about it forever. And the best books, the best films, are probably yet to come.”